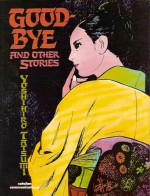

By Yoshihiro Tatsumi (Catalan Communications)

ISBN: 0-87416-056-1

Don’t believe your loved ones: sometimes size really does make a difference.

Shuffling along my seemingly infinite shelves the other day I spotted a graphic album I haven’t really looked at in years.

It was an album-sized (275x210mm) black-&-white collection of Japanese human-interest dramas translated into English from a Spanish compilation and was, when I bought it, my first introduction to the incredible creative force that is Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

Since then I’ve become familiar with most of his translated works but the other day was the first time that I’ve actually compared the scale of his art in traditional manga formats with the big, bold nigh-abstract expansions of a really expansive page.

The sheer emotional power delivered by going large is just incomprehensible…

Beginning in the 1950s, compulsive storyteller Yoshihiro Tatsumi worked at the edges of the burgeoning Japanese comics industry, toiling for whoever would hire him, whilst producing an absolutely vast canon of deeply personal, agonisingly honest and blisteringly incisive cartoon critiques.

These dissections, queries and homages remorselessly explored the Human Condition as endured by the lowest of the low in a beaten nation and shamed culture which utterly, ferociously and ruthlessly re-invented itself during his lifetime.

Tatsumi was born in 1935 and after surviving war and the reconstruction of Japan he devoted most of his life to mastering – if not inventing – a new form of comics storytelling, now known universally as Gekiga or “Dramatic Picturesâ€.

This was in contrast to the flashy and fancifully escapist entertainment of Manga – which translates as “Irresponsible†or “Foolish Pictures†– and specifically targeted children in the years immediately following the cessation of hostilities.

If he couldn’t find a sympathetic Editor, Tatsumi self-published his darkly beguiling wares in DÅjinshi or “Vanity projects†where his often open-ended, morally ambiguous, subtly subversive underground comics literature gradually grew to prominence; especially as those bland funnybook-consuming kids grew up in a socially-repressed, culturally-occupied country and began to rebel.

Topmost amongst their key concerns were Cold War politics, the Vietnam War, ubiquitous inequality and iniquitous distribution of wealth and opportunity, so the teen upstarts sought out material that addressed their maturing sensibilities and found it in the works of Tatsumi and a growing band of deadly serious cartoonists with something to say…

Since reading comics beyond childhood was seen as an act of rebellion – like digging Rock ‘n’ Roll a decade earlier in the USA and Britain – these kids became known as the “Manga Generation†and their growing influence allowed comics creators to grow beyond the commercial limits of their industry and tackle adult stories and themes in what rapidly became a bone fide art form.

Even “God of Comics†Osamu Tezuka eventually found his mature author’s voice in Gekiga…

Tatsumi uses art as a symbolic tool, with an instantly recognisable repertory company of characters pressed into service over and again as archetypes and human abstracts of certain unchanging societal aspects and responses. Moreover, he has a mesmerising ability to portray situations with no clean or clear-cut resolution: the tension and sublime efficacy revolves around carrying the reader to the moment of ultimate emotional crisis and leaving you suspended there…

Narrative themes of sexual frustration, falls from grace or security, loss of heritage and pride, human obsolescence, claustrophobia and dislocation, obsession, provincialism, impotence, loneliness, poverty and desperate acts of protest are perpetually explored by a succession of anonymous bar girls, powerless men, grasping spouses, ineffectual loners, wheedling, ungrateful family dependents and ethically intransigent protagonists through recurring motifs such as illness, forced retirement, disabled labourers and sexual inadequacy all lurking in ramshackle dwellings, endless dirty alleyways, tawdry bars and sewers too often obstructed by discarded lives and dead babies…

Following an expansive discourse on ‘Japanese Comics’ by José Mariá Carandell, the well-travelled dramas begin with ‘Just a Man’ as, at the end of his working life, Mr. Manayana is sidelined by all the younger workers: all except kind Ms. Okawa whose kindly solicitousness rekindles crude urgings in the former soldier and elderly executive. With his wife and daughter already planning how to spend his pension, Manayana rebels and blows it all on wine, women and song, but even when he achieves the impossible manly dream with the ineffable Ms. Okawa, he is plagued by impotence and guilt…

‘The Telescope’ then brings a crippled man too close to an aging exhibitionist who needs to be seen conquering young women, leading only to recrimination and self-destruction…

In ‘Life is So Sad!‘ a junior and senior bar girl clean up after the night’s toil, but young Akemi is clumsily preoccupied…

It’s time to visit her husband in prison. He is a changed, fierce and brutalised man and doesn’t believe she has kept herself for him all these years. When he threatens to become her pimp after his release, she is reluctantly forced to take extreme action…

Down in ‘The Sewers’ whilst daily unclogging the city’s mains, a harassed young man finds himself no longer reacting to the horror of what the people above discard: baskets, boxes, babies… even when the deceased detritus is his own…

‘Just Passing Through’ sees Kyoko return to her husband and mother-in-law after an unexplained 2-year absence. Nothing has changed. Her forgiving man froze time on the day she vanished: even the calendar has not moved a single day.

As he patiently rejoices in her return Kyoko realises the horrific passive-aggressive nature of his gesture and heads once more for the door…

‘Progress is Wonderful!’ sees an over-worked sperm donor foolishly allowing his latest “inspiration†to get too close with catastrophic results, after which the semi-autobiographical and eponymous ‘Good-Bye’ describes the declining relationship between prostitute “Maria†– who courts social ignominy by going with the American GI Joes – and her dissolute father; once a proud soldier of Japan’s beaten army, now reduced to cadging cash and favours from her.

Her dreams of escape to America are shattered one day and in her turmoil she pushes her father too far and he commits an act there’s no coming back from…

‘Unwanted’ brings the volume to conclusion by relating the inevitable fate of a placard carrier advertising a seedy massage parlour. Why can he get on with tawdry prostitutes of the street but not his own wife, with her constant carping about her unwanted pregnancy? Why is murder the only rational option?

This epic volume was, it transpires, wholly unauthorised but I was blown away by the seductive and wholly entrancing simplicity of Mr. Tatsumi’s storytelling and bleak, humanist subject matter.

Now that I know just when these stark, wry, bittersweet vignettes, episodes and stories of cultural and social realism were first drawn (between 1969-1977) it seems as if a lone voice in Japanese comics had independently and synchronistically joined the revolution of Cin̩ma v̩rit̩ and the Kitchen Sink Dramas of playwrights and directors like John Osborne, Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson Рnot to mention Ken Loach and Joe Orton Рwhich gripped the West in the 1960s and which have shaped the critical and creative faculties of so many artists and creators ever since.

Tatsumi, like Robert Crumb and Harvey Pekar, worked for decades in relative isolation producing compelling, bold, beguiling, sordid, intimate, wryly humorous, heartbreaking and utterly uncompromising strips dealing with uncomfortable realities, social alienation, excoriating self-examination and the nastiest and most honest arenas of human experience. They can in fact be seen as brother auteurs and indeed inventors of the “literary†or alternative field of graphic narrative which, whilst largely sidelined for most of their working lives, has finally emerged as the most important and widely accepted avenue of the comics medium.

These are stories no serious exponent or fan of comics can afford to miss… and they’re even better printed bigger…

© 1987 Yoshihiro Tatsumi. All Rights Reserved.