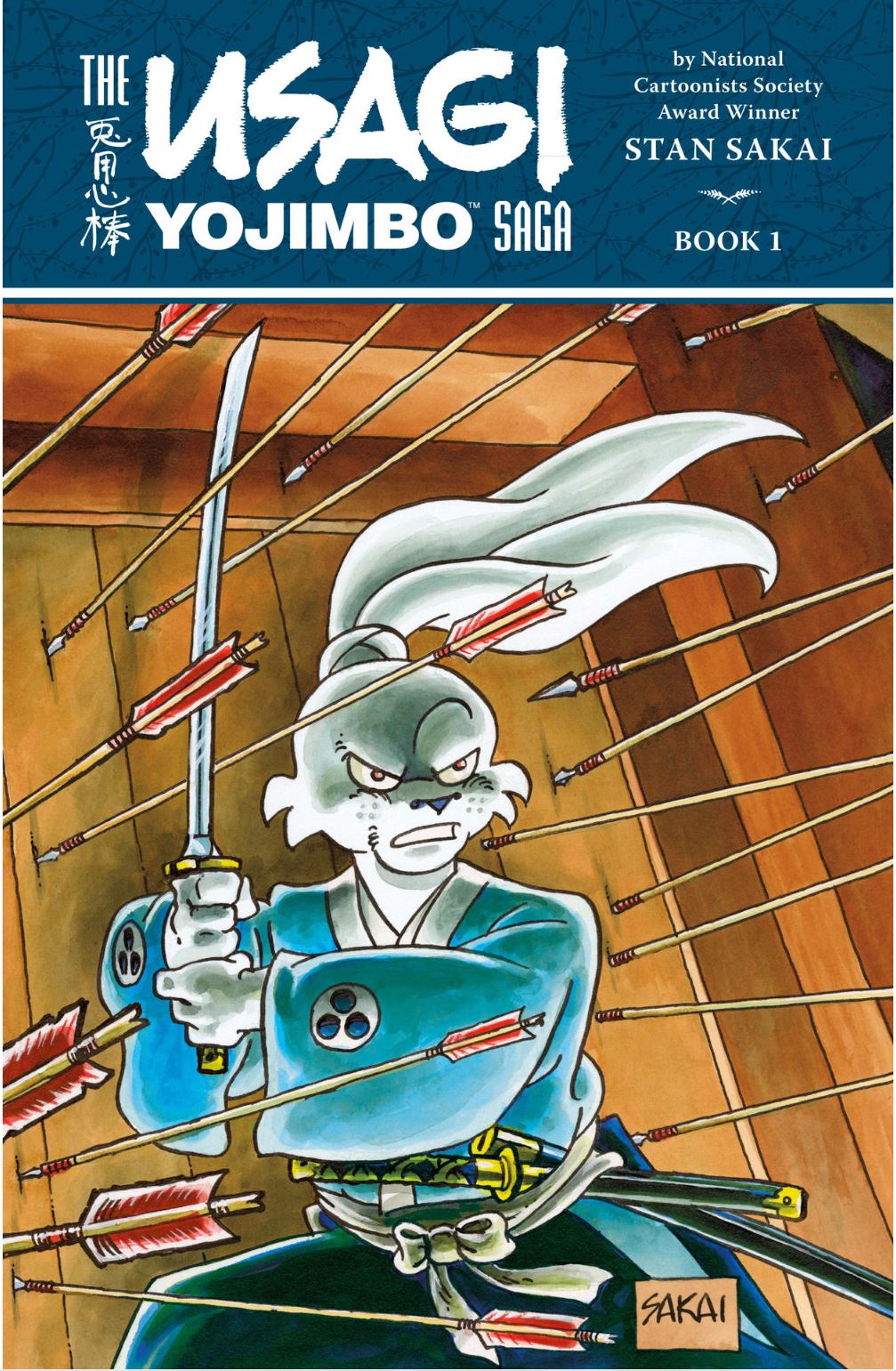

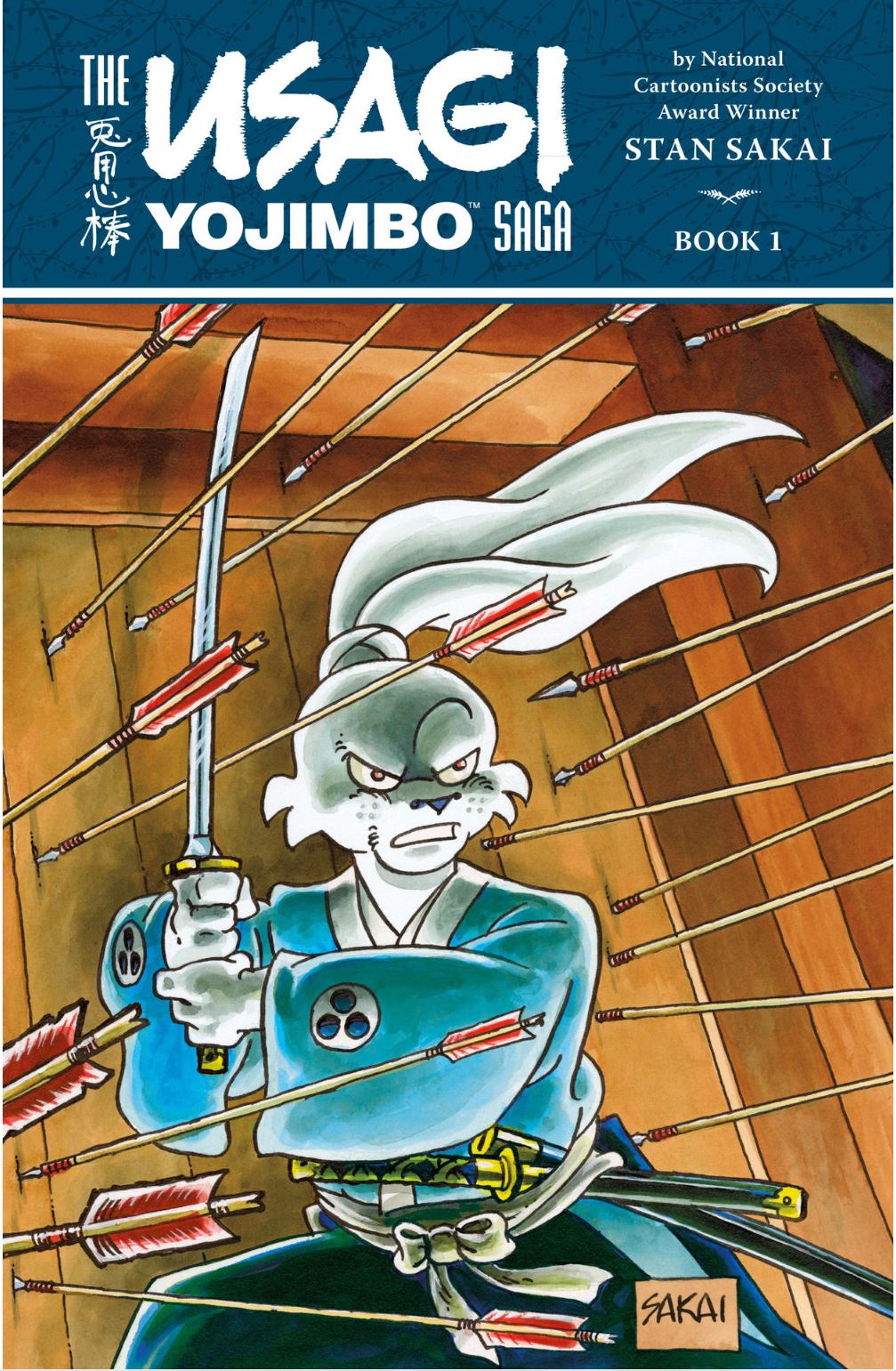

By Stan Sakai (Dark Horse Books)

ISBN: 978-1-61655-671-6(HB) 978-1-61655-609-9(TPB) eISBN: 978-1-63008-081-5

Back in 1955, when Stan Sakai was two years old, the family moved from Kyoto, Japan to Hawaii. Growing up in a cross-cultural paradise, he graduated from the University of Hawaii with a BA in Fine Arts, before leaving to pursue further studies at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design in California. His early forays into comics were as a letterer – most famously for Groo the Wanderer and the Spider-Man newspaper strip – before his nimble pens and brushes found a way to express his passion for Japanese history, legend and Akira Kurosawa films, inspirationally transforming a proposed story about a human historical hero into one of the most enticing and impressive fantasy sagas of all time.

Usagi Yojimbo (“rabbit bodyguard”) first appeared in 1984’s Albedo Anthropomorphics #1: a background character in Stan Sakai’s The Adventures of Nilson Groundthumper and Hermy, and premiering amongst assorted furry ‘n’ fuzzy folk. He soon graduated to a nomadic solo act in Critters, Amazing Heroes, Furrlough and the Munden’s Bar back-up series in Grimjack. Although the expansive period epic stars sentient animals and details the life of a peripatetic Lord-less Samurai eking out as honourable a living as possible as a Yojimbo (bodyguard-for-hire), the milieu and scenarios scrupulously mirror Japan’s Feudal Edo Period (roughly 16th-17th century AD by Western reckoning) whilst simultaneously referencing other cultural icons from sources as varied as Zatoichi to Godzilla.

Miyamoto Usagi is brave, noble, industrious, honest, sentimental, gentle, artistic, empathetic, long-suffering and conscientious: a rabbit devoted to the tenets of Bushido and utterly unable to turn down any request for help or ignore the slightest evidence of injustice. As such, his destiny is to be perpetually drawn into an unending panorama of incredible situations.

Despite changing publishers a few times, the Roaming Rabbit has been in publication since 1987, with nearly 60 assorted collections of comics and at least 5 art books to date. He’s guest-starred in many other series (most notably Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and its TV incarnation) and even made it into his own small-screen Netflix show – albeit in a futuristic setting. There are high-end collectibles, art prints, computer games and RPGs, spin-off comics serials and lots of toys. Author Sakai and his creation have won numerous awards both within the Comics community and amongst the greater reading public… And it’s still more educational, informative and authentic than any dozen Samurai sagas you can name…

The title is as much a wanderer as its star, migrating from Fantagraphics to Mirage, Dark Horse, Radio Comix, IDW and Dark Horse again under Sakai’s own Dogu Publishing imprint. None of that matters: what you need to know is that this stuff is superb and no matter which version you see, you will be a better being for reading it…

This guest-star stuffed premiere monochrome masterpiece draws together yarns released by Mirage Publishing as Usagi Yojimbo volume 2 #1-16 and Usagi Yojimbo volume 3 #1-6

Following a fulsome Foreword from former editor Jamie S. Rich, pictorial rundown of dramatis personae in ‘Cast of Characters’ and rousing strip recap ‘Origin Tale’, an evocative Introduction from legendary illustrator and Dean of Dinosauria William Stout leads into the magnificent and ever-unfolding medieval mystery play…

It begins with 3-parter ‘Shades of Green’ wherein Usagi and crusty companion Gennosuke (an irascibly bombastic, money-mad bounty-hunter and conniving thief-taking Indian rhino with a heart of gold) are recruited by Kakera: a ratty shaman in dire need of protection from the dwindling remnants of the once-mighty Neko Ninja clan. The former imperial favourites have fallen upon hard times since they and the Ronin Rabbit crushed the Dragon Bellow plot of rebel Lord Takamuro. Now, bat assassins of the Komori Ninja clan are constantly harrying, harassing and actively seeking to supplant them in Lord Hikiji’s service…

Chunin (deputy leader) Gunji believes the rodent wizard would make a mighty useful slave, and is scheming to overthrow the new – female – clan chief Chizu whilst acquiring him…

With the Neko’s trap closing around them all, the sagacious sensei summons spirits of four fantastic fighters to aid Usagi and Gen. These phantoms promptly possess a quartet of little Kame (tortoises) and are reshaped into adolescent amphibian Ninja Turtles, identifying themselves as Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and Donatello. Crucially, Usagi has fought beside one of their number before…

Subsequent battles go badly and eventually Gunji’s forces make off with Kakera-sensei. As Usagi leads the remaining heroes in relentless pursuit, the conniving Chunin makes his move. Gunji’s attempt to assassinate Chizu is bloodily and efficiently ended by late-arriving Usagi who is astounded to be told by the lady he has saved that the Neko’s lethal interest in him is now at an end…

With Kakera rescued and Gunji dead, the adventure closes with the turtle spirits returning to their own place and time, leaving Gen and Usagi to follow their own (temporarily) separate roads before ‘Jizo’ offers a delightfully gripping interlude as a grieving mother dedicates a roadside shrine to her murdered child and ineffable Karma places the killers in the path of a certain justice-dispensing, long-eared wanderer…

Next comes a brace of stories offering elucidating glimpses of the rabbit’s boyhood. Once, Miyamoto Usagi was simply son to a small-town magistrate before being sent to spend his formative years learning the Way of Bushido from gruff and distant leonine hermit Katsuichi. The stern sensei taught not just superior technique and tactics, but also an ironclad creed of justice and restraint which would serve the Ronin well throughout his turbulent life.

In ‘Usagi’s Garden’ the callow pupil rebels against the arduous and undignified task of growing food until the lion delivers a subtle but lifechanging lesson, whilst in ‘Autumn’ a painful fall propels the lad into a nightmare confrontation with a monster who has trapped the changing of the seasons in a bamboo cage…

Two-part tale ‘Shi’ sees Usagi comes to the aid of a valley of poor farmers under constant attack by bullies and brigands seeking to force them from their impoverished homes. The thugs are secretly employed by a local magistrate and his ruthless brother who discovered gold under the peasants’ land and want to extract it without attracting the attention of the local Lord’s tax collectors. When the Ronin’s formidable skills stall the brothers’ scheme they hire a quartet of assassins whose collective name means “death”. However, the killers are far less trouble than the head farmer’s daughter Kimie, who has never seen someone as glamorous or attractive as the soft-spoken defrocked samurai…

Although there are battles aplenty for Usagi, the brothers’ remorseless greed ends them before the Yojimbo can…

Delightful silent comedy follows as ‘The Lizard’s Tale’ pantomimically depicts the ronin playing unwilling Pied Piper and guardian to a wandering flock of tokagé lizards (ubiquitous, omnivorous reptiles populating the anthropomorphic world, replacing scavenger species like rats, cats and dogs in the fictitious ecosystem). The rambunctious trouble-magnets repay the favour when the wanderer is ambushed in snow-drowned mountains by vengeful bandits…

‘Battlefield’ is a 3-chapter fable sharing a key moment and boyhood turning point in the trainee warrior’s life. It begins when a mind-broken, fleeing soldier shatters the boy’s childish dreams of warrior glory. The fugitive is a survivor of the losing side in a mighty battle and his sorry state forces Usagi to rethink his preconceptions of war. Eager to ram home the lesson, Katsuichi takes his pupil to the battlefield where peasants and scavengers busily snatch up whatever they can from the scattered corpses. Usagi is horrified. To take a samurai’s swords is to steal his soul, but even so, a little later he cannot stop himself picking up a fallen hero’s Wakizashi (short sword)…

After concealing the blade in a safe place, the apprentice is haunted by visions of the unquiet corpse and sneaks off to return the stolen steel soul. Caught by soldiers who think him a scavenging looter and about to lose his thieving hands, little Miyamoto is saved by the intervention of victorious Great Lord Mifune. The noble looks into the boy’s face and sees something honest, honourable and – perhaps one day – useful…

Following an Introduction on ‘Classic Storytelling’ from James Robinson, the ronin roaming resumes with ‘The Music of Heaven’ as Miyamoto and a wandering flock of tokagé lizards encounter a gentle, pious priest whose life is dedicated to peace, music and enlightenment. When their paths cross again later, the rabbit narrowly avoids being murdered by a ruthless assassin who has since killed and impersonated holy man Komuso in an attempt to catch Usagi off guard. Evocative and movingly spiritual, this classic of casual tragedy perfectly displays the vast range of storytelling Sakai can pack into the most innocuous of tales.

More menaces from the wanderer’s past reconnect in ‘The Gambler, The Widow and the Ronin’ as a professional conman who fleeces villagers with rigged samurai duels plies his shabby trade in just another little hamlet. Unfortunately, this one is home to his last stooge’s wife, and to make matters worse, whilst his latest hired killer Kedamono is attempting to take over the business, the long-eared nomad who so deftly dispatched his predecessor Shubo strolls into town looking for refreshments…

Again forced into a fight, Miyamoto makes short work of Kedamono, leaving the smug gambler to safely flee with the entire take. Slurping back celebratory servings of sake, the villain has no idea the inn where he relaxes employs a vengeful widow and mother who knows just who really caused her man’s death…

A note of portentous foreboding informs ‘The Nature of the Viper’, opening a year previously when a boisterous, good-hearted fisherman pulled a body out of the river and nursed his amazingly still breathing catch back to health. If he expected gratitude or mercy, the peasant was sadly mistaken, as the fondling explained whilst killing his benefactor as soon as he was able. The ingrate is Jei: a veritable devil in mortal form, who believes himself a “Blade of the Gods” and singled out by the Lords of Heaven to kill the wicked. The maniac makes a convincing case: when he stalked Usagi, the monster was struck by a fortuitous – or possibly divinely sent – lightning bolt but is still going strong and keenly continuing to hunt the Ronin.

‘Slavers’ begins a particularly dark journey for our hero as Usagi stumbles across a boy in chains escaping from a bandit horde. Little Hiro explains how the ragtag rogues of wily “General” Fujii have captured a whole town: making the inhabitants harvest their crops for the scum to steal…

Resolved to save them, the rabbit infiltrates the captive town as a mercenary seeking work, but is soon exposed and taken prisoner. ‘Slavers Part 2’ finds Miyamoto stoically enduring the General’s tortures until the boy he saved bravely returns the favour – after which the Yojimbo’s vengeance is awesome and terrible…

However, even as the villagers rebel and take back their homes and property, chief bandit Fujii escapes, taking Usagi’s daish? (matched long and short swords) with him. To take a samurai’s swords is to steal his soul, and the monster not only has them but continually dishonours them by slaughtering innocents as he flees the ronin’s relentless pursuit.

‘Daish? – Part One’ opens with a hallowed sword-maker undertaking the sacred process of crafting blades and the harder task of selecting the right person to buy them. Three hundred years later, Usagi is on the brink of madness as he follows Fujii’s bloody trail, pitilessly picking off the General’s remaining killers whilst attempting to redeem those soiled dispensers of death. The chase leads to another town pillaged by Fujii where Miyamoto almost refuses to aid a wounded man… until one woman accuses him of being no better than the beast he hunts…

Shocked back to his senses, the yojimbo saves the elder’s life and in gratitude the girl Hanako offers to lead him to where Fujii was heading. ‘Mongrels’ changes tack as erstwhile ally and hard-to-love friend Gennosuke re–enters the picture. The bombastic, money-mad bounty-hunter and conniving thief-taker is on the prowl for suitably profitable prospects when he meets The Stray Dog: his greatest rival in the unpopular profession of cop-for-hire.

After some posturing and double-dealing wherein each tries to edge out the other in the hunt for Fujii, they inevitably come to blows and are only stopped by the fortuitous intervention of the Rabbit Ronin…

‘Daish? – Part Two’ sees the irascible rugged individualists form a shaky truce in their overweening hunger to tackle the General. Mistrustful of each other, they nevertheless cut a swathe of destruction through Fujii’s regrouped band, but even after furious Usagi regains his honour swords there is one last betrayal in store…

Older, wiser and generally unharmed, Gen and Usagi part company again as ‘Runaways’ delves deeper into the wanderer’s past. Stopping in a town he hasn’t visited in decades, the rabbit hears a name called out and his mind retreats to a time when he was a fresh young warrior in the service of Great Lord Mifune.

Young princess Takani Kinuko had been promised as bride to trustworthy ally Lord Hirano and the rabbit was a last-minute replacement as leader of the “babysitting” escort column to her impending nuptials. When an overwhelming ambush eradicated the party, Usagi was forced to flee with the stuck-up brat: both of them masquerading as carefree, unencumbered peasants as he strove to bring her safely to her future husband past an army of ninjas killers.

The poignant reverie concludes in ‘Runaways – Part 2’ as valiant hero and spotless maiden fell in love whilst fleeing from pitiless, unrelenting marauders. Successful at last, their social positions naturally forced them apart once she was safely delivered.

Shaken from his memories, the ronin moves on, tragically unaware he was not the only one recalling those moments and pondering what might have been…

Originally collected as The Brink of Life and Death, an evocatively enticing third tranche of torrid tales opens with ‘Discoveries’ – a heartfelt and enthusiastic Introduction from comics author Kurt Busiek – before more epics of intrigue intermingle with vignettes of more plebeian dramas and even an occasional supernatural thriller, all tantalisingly tinged with astounding martial arts action and drenched in wit, irony, pathos and tragedy…

Far away from our nomadic star a portentous interlude occurs as a simple peasant and his granddaughter are attacked by bandits. The belligerent scum are about to compound extortion and murder with even more heinous crimes when a stranger with a ‘Black Soul’ stops them…

This is Jei and nothing good comes from even innocent association with the Blade of the Gods. Still pursuing his crusade, the monster deals most emphatically with the criminals before “permitting” orphaned granddaughter Keiko to join him…

‘Kaise’ then finds Miyamoto Usagi befriending a seaweed farmer who’s experiencing a spot of bother with his neighbours. At peace with himself amongst hard-toiling peasants, Usagi is soon embroiled in their escalating battle with a village of rival seaweed sellers – previously regarded as helpful and friendly – and quickly realises scurrilous merchant Yamanaka is fomenting discord and unrest between his suppliers to make extra profit…

In a roadside hostelry ‘A Meeting of Strangers’ introduces a formidable female warrior to the ever-expanding cast as the Lepine Legend graciously offers a fellow weary mendicant the price of a drink. A professional informer then sells Usagi out to still-smarting Yamanaka and lethally capable Inazuma has ample opportunity to repay her slight debt to the Rabbit Ronin when he’s ambushed by an army of hired brigands…

Despite – or because – it is usually one of the funniest comics on the market, occasionally Usagi Yojimbo will brilliantly twist readers’ expectations with tales that rip your heart apart. Such is the case with ‘Noodles’, as the ronin meets again street performer, shady entertainer and charismatic pickpocket Kitsune. She was plying all her antisocial trades in a new town just as eternally-wandering Usagi rolls up. The little metropolis is in uproar at a plague of daring robberies and when inept enforcers employed by Yoriki (Assistant Commander) Masuda try – and painfully fail – to arrest the long-eared stranger as a probable accomplice, the ferociously resistant rabbit earns the instant enmity of the pompous official.

Following the confrontation, a hulking, mute soba (buckwheat noodle) vendor begins to pester the still-annoyed ronin and eventually reveals he’s carrying elegant escapologist Kitsune in his baskets. Astounded, the yojimbo renews his acquaintance with her before the affable thieves go on their way, unaware that trouble and tragedy are just around the corner…

The town magistrate is leaning heavily on his Yoriki to end the crimewave but has no conception Masuda is actually in the pay of a vicious gang carrying out most of the thefts. What they all need is a convincing scapegoat to pin the blame on, and poor dumb peasant Noodles is ideal – after all, he can’t even deny his guilt…

With a little sacrificed loot planted, the gentle giant becomes a perfect patsy and before Usagi and Kitsune even know he’s been taken, the simple fool has been tried and horrifically executed. ‘Noodles Part 2’ opens as our aggrieved heroes frantically dash for the public trial and almost immediate crucifixion. Neither pickpocket nor bodyguard can save the innocent stooge: all they can do is swear to secure appropriate vengeance and a kind of justice…

In sober mien the rabbit roves on, stumbling into a house of horror and case of possession. ‘The Wrath of the Tangled Skein’ finds Usagi returning to a region plagued by demon-infested forests. Offered hospitality at a merchant’s house, he subsequently saves the daughter from doom at the claws of a demonic Nue (tiger/fox/pig/snake devil), but is almost too late and only alerted to a double dose of danger when a Bonze (Buddhist Priest) arrives to exorcise the poor child – just like the cleric already praying over the afflicted waif upstairs…

This duel with the forces of hell leads into ‘The Bonze’s Story’ as Usagi befriends the real priest and learns how misfortune and devotion to honour compelled elite samurai Sanshobo to put aside weapons and war in search of greater truths and inner peace…

Political intrigue and explosive espionage return to the fore in ‘Bats, the Cat, & the Rabbit’ as Neko ninja chief Chizu re-enters Usagi’s life, fleeing a flight of rival Komori (bat) ninjas. These winged horrors are determined to possess a scroll containing the secrets of making gunpowder and, after a tremendous, extended struggle, the exhausted she-cat cannot believe her rabbit companion is willing to simply hand it over. She soon shrugs it off, after all the Komori have fallen into her trap and quickly regret testing the purloined formula…

The peripatetic yojimbo then walks into a plot to murder Great Lord Miyagi involving infallible unseen assassin Kuroshi at ‘The Chrysanthemum Pass’. Although the valiant wanderer is simply aiding karma to a just outcome despite overwhelming odds and a most subtle opponent, this act will have appalling repercussions in days ahead…

Hunted woman and deadly adept Inazuma then proves ‘Lightning Strikes Twice’ when found – as always – at the heart of a storm of hired blades trying to kill her. However, during one peaceful moment, she makes time to share with a fellow swordsmaster the instructive tale of a dutiful daughter who married the wrong samurai. By exacting rightful vengeance upon his killer, she won the undying hatred of a powerful lord and set her own feet irredeemably upon the road of doom…

Rounding out in this epic collection are copious ‘Story Notes by Stan Sakai’, a full-colour ‘Gallery’ of the covers from both comic books and their attendant paperback compilations, annotated ‘Cover Sketches’ and designs, plus biographical data ‘About the Author’.

Fast-paced yet lyrical, informative and funny, the saga alternately bristles with tension and thrills and frequently crushes your heart with astounding tales of pride and tragedy, evil and duty. Bursting with veracity and verve, Usagi Yojimbo is the perfect comics epic: a monolithically magical, irresistibly appealing tale to delight devotees and make converts of the most hardened haters of “funny animal” stories.

Text and illustrations © 1993-1998, 2014 Stan Sakai. All rights reserved. Foreword © 2014 Jamie S. Rich. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles © 2014 Viacom International, Inc. All rights reserved. All other material and registered characters are © and TM their respective owners. Usagi Yojimbo and all other prominently featured characters are registered trademarks of Stan Sakai.