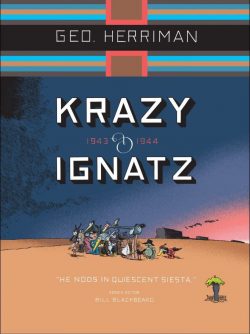

By George Herriman, edited by Bill Blackbeard (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-56097-932-6 (TPB)

In a field positively brimming with magnificent and eternally evergreen achievements, Krazy Kat is – for most cartoon cognoscenti – the pinnacle of pictorial narrative innovation: a singular and hugely influential body of work which shaped the early days of the comics industry and elevated itself to the level of a treasure of world literature.

Krazy & Ignatz, as it is dubbed in these gloriously addictive archival Fantagraphics tomes, is a creation which must always be appreciated on its own terms. Over the decades the strip developed a unique language – simultaneously visual and verbal – whilst delineating the immeasurable variety of human experience, foibles and peccadilloes with unfaltering warmth and understanding… and without ever offending anybody. Baffled millions, perhaps, but offended… no.

It certainly went over the heads and around the hearts of far more than a few, but Krazy Kat was never a strip for dull, slow or unimaginative people: those who simply won’t or can’t appreciate the complex, multi-layered verbal and cartoon whimsy, absurdist philosophy or seamless blending of sardonic slapstick with arcane joshing. It is still the closest thing to pure poesy narrative art has ever produced.

George Joseph Herriman (August 22, 1880-April 25, 1944) was already a successful cartoonist and journalist in 1913 when a cat and mouse who’d been noodling about at the edges of his domestic comedy strip The Dingbat Family/The Family Upstairs graduated to their own feature. Mildly intoxicating and gently scene-stealing, Krazy Kat subsequently debuted in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal on Oct 28th 1913 and – by sheer dint of the overbearing publishing magnate’s enrapt adoration and direct influence and interference – gradually and inexorably spread throughout his vast stable of papers.

Although Hearst and a host of the period’s artistic and literary intelligentsia (such as Frank Capra, e.e. Cummings, Willem de Kooning, H.L. Mencken and more) adored the strip, many local and regional editors did not; taking every potentially career-ending opportunity to drop it from those circulation-crucial comics sections designed to entice joe public and the general populace.

Eventually the feature found its true home and sanctuary in the Arts and Drama section of Hearst’s papers. Protected there by the publisher’s unshakable patronage and enhanced with the cachet of enticing colour, Kat & Ko. flourished unhampered by editorial interference or fleeting fashion, running generally unmolested until Herriman’s death on April 25th 1944.

This final collection covers the final days of the feature as Herriman succumbed slowly and painfully to cirrhosis caused by Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eschewing the standard policy of finding a substitute to carry on the strip, Hearst decreed that Krazy Kat would die with its creator and sole ambassador.

It was no real sacrifice to profit, but the culmination to years of grand tribute to unique mastery. The strip had declined in syndication for years. By the 1930s it was featured in only 35 papers, but despite that the publisher – acting more as renaissance-era artistic patron than hard-bitten businessman – refused Herriman’s every earnest request that his salary be reduced to fit his dwindling circulation. In 1935 Hearst responded to the requests by promoting the feature to the full-page, full-colour glory it enjoyed until the end.

The epic’s basic premise is simple: Krazy is an effeminate, dreamy, sensitive and romantic feline, hopelessly in love with Ignatz Mouse; a venal everyman, rude, crude, brutal, mendacious and thoroughly scurrilous.

Ignatz is a truly, proudly unreconstructed male and early forerunner of the men’s rights movement: drinking, stealing, fighting, conniving, constantly neglecting his wife and innumerable children and always responding to Krazy’s genteel advances by clobbering the Kat with a well-aimed brick. These he obtains singly or in bulk from noted local brick-maker Kolin Kelly. The smitten kitten apparently always misidentifies these gritty gifts as tokens of equally recondite affection showered upon him in the manner of Cupid’s fabled arrows…

By the time of these tales it’s not even a response, except perhaps a conditioned one: the mouse still spends most of his time, energy and ingenuity in launching missiles at the mild moggy’s bonce. He can’t help himself, and Krazy’s day is bleak and unfulfilled if the hoped-for assault doesn’t happen. However, in these concluding episodes even that fiery warped passion has somewhat cooled: often attempted in perfunctory manner and frequently resulting in failure: just like any loving couple in their twilight years together…

The final critical element completing an anthropomorphic eternal triangle is lawman Offissa Bull Pupp: utterly besotted with Krazy, professionally aware of the Mouse’s true nature, yet hamstrung by his own amorous timidity and sense of honour from permanently removing his devilish rival for the foolish feline’s affections. Krazy is, of course, blithely oblivious to the perennially “Friend-Zoned†Pupp’s dolorous dilemma…

Secondarily populating an ever-mutable stage are a big supporting cast of inspired bit players such as terrifying deliverer of unplanned babies Joe Stork; unsavoury huckster Don Kiyoti, hobo Bum Bill Bee, portal-packing Door Mouse, self-aggrandizing Walter Cephus Austridge, inscrutable, barely intelligible Chinese mallard Mock Duck, dozy Joe Turtil and snoopy sagacious fowl Mrs. Kwakk Wakk, plus a host of other audacious animal crackers all equally capable of stealing the limelight and even supporting their own features.

The exotic, quixotic episodes occur in and around the Painted Desert environs of Coconino (patterned on the artist’s vacation retreat in Coconino County, Arizona) where surreal playfulness and the fluid ambiguity of the flora and landscape are perhaps the most important member of the cast.

The strips themselves are a masterful mélange of unique experimental art, cunningly designed, wildly expressionistic and strongly referencing Navajo art forms whilst graphically utilising sheer unbridled imagination and delightfully evocative lettering and language. This last is particularly effective in these later tales: alliterative, phonetically, onomatopoeically joyous with a compelling musical force and delicious whimsy (“goldin moom bims†or “there is a heppy lend, furfur away…â€).

Yet for all our high-fallutin’ intellectualism, these comic adventures are poetic, satirical, timely, timeless, bittersweet, self-referential, fourth-wall bending, eerily idiosyncratic, outrageously hilarious escapades encompassing every aspect of humour from painfully punning shaggy dog stories to riotous, violent slapstick. Kids of any age will delight in them as much as any pompous old git like me and you…

There’s been a wealth of Krazy Kat collections since the late 1970s when the strip was first rediscovered by a better-educated, open-minded and far more accepting generation. This bittersweet final chapter covers all the strips from 1943 to the middle of 1944 in a comfortably hefty (231 x 305 mm) softcover edition – and is also available as a suitably serene digital edition.

With far fewer strips to catalogue, this edition is bulked up with a veritable treasure trove of unique artefacts: plenty of candid photos, personal correspondence, vast stores of original strip art and many astounding examples of Herriman’s personalised gifts and commissions (gorgeous hand-coloured artworks featuring the cast and settings), as well as a section on the rare merchandising tie-ins and unofficial bootleg items.

Tribute, commentary and analysis is provided by Bill Blackbeard’s final Introduction ‘The Tragedy of a Man with an Absent Mind’ and Jeet Heer and Michael Tisserand’s heavily-illustrated essay ‘Herriman’s Last Days (or, All Kats are Gray in the Dark)’ offering superb analysis of the unique talent celebrated herein. This inevitably leads to those superb cartoons, resuming with January 3rd 1943 and a tumultuous exchanging of gifts between cast regulars…

Due to the author’s declining health and perhaps the several personal tragedies that afflicted him in later life, the story atmosphere is mostly ruminatory and philosophical. It is also tinged with topical anxieties as World War II touches even the distant hills and mesas of Coconino. The trials of torrid triangular romance still play out as painfully and hilariously ever, but are balanced by more considered gags. Oblique references to the real world abound: a tortoise named Tank shambles about, Krazy is castigated for growing pretty flowers in the Victory Garden, and Ignatz is perforce compelled to handle bricks on a rationed, time-shared basis…

The usual parade of hucksters and conmen still abound, but pell-mell action, devious schemes and frantic chase gradually give way to comfortable chats and the occasional debate before inevitably concluding at the jail house…

Ignatz endures regular incarcerations and numerous forms of exile and social confinement, but with Krazy aiding and abetting, these sanctions seldom result in a reduction of cerebral contusions, whereas the plague of travelling conjurors, unemployed magicians and shady clairvoyants still make life hard for the hard-pressed constabulary and the gullible fools they target. Perhaps because of Herriman’s own vintage, many regular characters share a greater appreciation of infirmity and loss of drive, often reflected in the reduction of Krazy to a bit player in many strips.

Pupp suffers with his age, repeatedly trying labour-saving new policing appliances such as electrically booby-trapped or glue-drenched bricks and termites trained to chew on fired clay, and as a steady stream of displaced royals from conquered lands set up in the desert paradise and the phenomenon of zoot-suiters manifests, the forces of law and order seem harder-pressed every day.

Aged busybody Mrs Kwakk Wakk further expands her role of wise old crone and sarcastic Greek Chorus; confirming her status as a leading player. She has a mean and spiteful beak on her too, and whilst laconic vagabonds such as Bum Bill Bee continue their scams and schemes, the primary cast-members seem inclined to sit back and let them all get on with it……

Welcomingly as ever, there is still a solid dependence on the strange landscapes and eccentric flora for humorous or inspiration or simple aesthetic gratification, while all manner of weather and terrain play a large part in inducing anxiety, bewilderment and hilarity. As arthritis, increasing migraines and age took some of the artist’s physical dexterity, it seemed to liberate his eyes and compositional sensibilities. The later strips are astounding sleek graphic exemplars of cunning design and hue on which the regulars play out their final lines…

The wonderment concludes with ore unearthed artistic treasures and one last instructional ‘Ignatz Mouse Debaffler Page’, providing pertinent facts, snippets of contextual history and necessary notes for the young and potentially perplexed.

Herriman’s epochal classic is a stupendous and joyous monument to gleeful whimsy: in all the arenas of Art and Literature there has never been anything like these strips which have inspired comics creators and auteurs in fields as disparate as prose fiction, film, dance, animation and music, whilst fulfilling its basic function: engendering delight and delectation in generations of wonder-starved fans.

If, however, you are one of Them and not Us, or if you actually haven’t experienced the gleeful graphic assault on the sensorium, mental equilibrium and emotional lexicon carefully thrown together by George Herriman from the dawn of the 20th century until the dog days of World War II, this astounding compendium is a most accessible way to do so.

© 2008, 2015 Fantagraphics Books. All rights reserved.