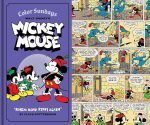

By Floyd Gottfredson, Ted Osborne, Ted Thwaites, Manual Gonzales, Al Taliaferro, Julius Svensden, Merrill De Maris, Bill Walsh, Roy Williams, Del Connell, Tony Strobl, Bill Wright & Chuck Fuson, Bob Grant & various: edited by David Gerstein & Gary Groth (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-686-7 (HB/Digital edition)

This book includes some Discriminatory Content produced during less enlightened times.

As collaboratively co-created by Walt Disney & Ub Iwerks, Mickey Mouse was first seen – if not heard – in silent cartoon Plane Crazy. The animated short fared poorly in a May 1928 test screening and was promptly shelved. That’s why most people who care cite Steamboat Willie – the fourth Mickey feature to be completed – as the debut of both the mascot mouse and co-star/paramour Minnie Mouse, since it was the first to be nationally distributed, as well as the first animated feature with synchronised sound. The astounding success of the short led to a subsequent and rapid release of fully completed predecessors Plane Crazy, The Gallopin’ Gaucho and The Barn Dance, once they too had been given soundtracks. From those timid beginnings grew an immense fantasy empire, but film was not the only way Disney conquered hearts and minds. With Mickey a certified solid gold sensation, the mighty mouse was considered a hot property and was soon inducted into America’s most powerful and pervasive entertainment medium – comic strips…

Floyd Gottfredson was a cartooning pathfinder who started out as just another warm body in the Disney Studio animation factory. Happily, he slipped sideways into graphic narrative and evolved into a pioneer of pictorial narratives as influential as George Herriman, Winsor McCay and Elzie Segar. Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse entertained millions – if not billions – of eagerly enthralled readers and helped shape the very way comics worked. Via some of the earliest adventure continuities in comics history he took a wildly anarchic animated rodent from slap-stick beginnings and transformed a feisty everyman underdog into a crimebuster, detective, explorer, lover, aviator and cowboy. Mickey was the quintessential two-fisted hero as necessity and locale demanded. In later years, as tastes – and syndicate policy – changed, Gottfredson steered that self-same wandering warrior towards a sedate, gently suburbanised lifestyle, employing crafty and clever sitcom gags suited to a newly middle-class and financially comfortable America: comprising a 50-year career generating some of the most engrossing continuities the comics industry has ever enjoyed.

Arthur Floyd Gottfredson was born in 1905 in Kaysville, Utah, one of eight siblings in a Mormon family of Danish extraction. Injured in a youthful hunting accident, Floyd whiled away a long recuperation drawing and studying cartoon correspondence courses. By the 1920s he had turned professional, selling cartoons and commercial art to local trade magazines and Big City newspaper the Salt Lake City Telegram. In 1928, he and wife Mattie moved to California where, after a shaky start, the compulsive doodler found work as an in-betweener with the burgeoning Walt Disney Studios. That was in April 1929, just before the Great Depression hit. Not long after that Gottfredson was personally asked by Walt to take over the newborn but already ailing Mickey Mouse newspaper strip. He would plot, draw and frequently script the strip across the next five decades: an incredible accomplishment by of one of comics’ most gifted exponents.

Veteran animator Ub Iwerks had initiated the print feature with Disney himself contributing, before artist Win Smith was brought in. The nascent strip was plagued with problems and young Gottfredson was only supposed to pitch in until a qualified regular creator could be found. His first effort saw print on May 5th 1930 (his 25th birthday) and Floyd just kept going for 50 years. On January 17th 1932, Gottfredson crafted the first colour Sunday page, which he also oversaw and often produced until retirement. At first he did everything, but in 1934 Gottfredson relinquished scripting, preferring plotting and illustrating the adventures to playing about with dialogue. Thereafter, collaborating wordsmiths included Ted Osborne, Merrill De Maris, Dick Shaw, Bill Walsh, Roy Williams & Del Connell. At the start and in the manner of a filmic studio system, Floyd briefly used inkers such as Ted Thwaites, Earl Duvall & Al Taliaferro, but by 1943 had taken on full art chores.

This superb archival compendium – part of a magnificently ambitious series collecting the creator’s entire canon – continues with his efforts from his thirties heyday to retirement in 1976. Initially – just like the daily feature – the Sunday strip was treated like an animated feature (and frequently promoted screen stories by adapting or continuing movies on the page) with diverse hands working under a “director” and each episode seen as a full gag with set-up, delivery and a punchline, usually all in service to an umbrella story or theme. Such was the format Gottfredson inherited from Walt Disney, and by the time of the material re-presented here it had evolved into a highly efficient system for delivering fun and adventure thanks to the tireless efforts of master storyteller, who knew how to spin out and embellish a yarn…

Following David Gerstein’s Introduction and a truly massive table of Contents, the show opens with preliminary features Setting the Stage. Unbridled fun and incisive revelations begin with J.B. Kaufman’s model-sheet stuffed Foreword ‘Mickey’s Sunday Best: Moving On’ introducing us to the pressures of this unique graphic world before Tom Neely’s equally image-packed Appreciation ‘Of Blots and Stressed-Out Bodies’ tells us more about Gottfredson himself, prior to the glories of the spoken picture as the comics delights begin with The Sundays: Mickey’s Rival and Helpless Helpers and Gag Strips: subdivided into ‘The Sundays, (Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse Stories)’ and each proudly preceded by Joe Torcivia’s Introductory Notes, starting with ‘Balancing Acts – And When Helpfulness Lacks’.

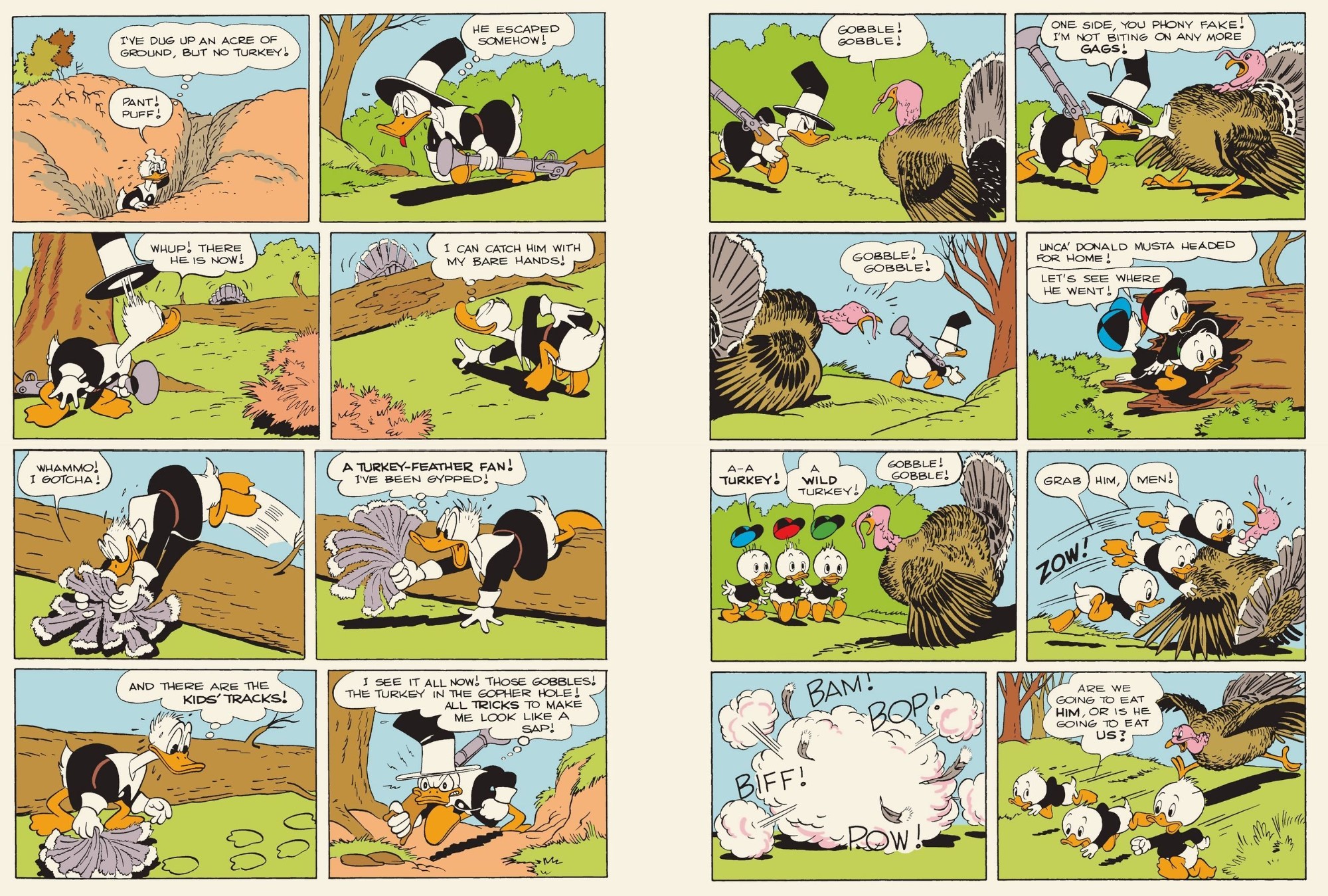

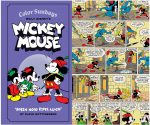

Then, spanning January 5th – 26th 1936, ‘Mickey’s Rival’ introduces our hero’s dark mirror antithesis in a sequence written by Ted Osborne, pencilled by Gottfredson and inked Ted Thwaites. Here a most manly, not to say thuggish and vulgar, fellow rodent named Mortimer makes major inroads courting Minnie and a month of escalating escapades – and even stern advice from Goofy – are ineffective. Ultimately, low cunning and unsportsmanlike tricks clear the path of true love and Mortimer is sent packing…

Done-in-one ‘Gag Strips’ run from February 2nd to 23rd with Al Taliaferro joining the creative trio mid-month: with Mickey and faithful hound Pluto dodging dog catchers, failing to open cans and bottles, falling foul of ice and snow and even street racing old cars with Donald Duck. Mickey then helps Goofy & Donald catastrophically “fix-up” Minnie’s house in themed sequence ‘Helpless Helpers’ (March 1st to 22nd) in advance of more ‘Gag Strips’ spanning March 29th to April 19th with the Mouse meeting burglars, bandits and floods whilst avoiding the dentist he really needs to see…

Stefano Priarone’s introductory text ‘Postmodern Times’ then ushers readers into compelling extended fantasy romp ‘The Robin Hood Adventure’ (April 19th to October 4th, with plot & pencils by Gottfredson, an Osborne script and Taliaferro inking): a story-within-a-story as ardent gardener Mickey is transported via beanstalk and magic book back to Sherwood Forest to for dashing derring-do, comical capers, swashbuckling swipes and satirical jibes.

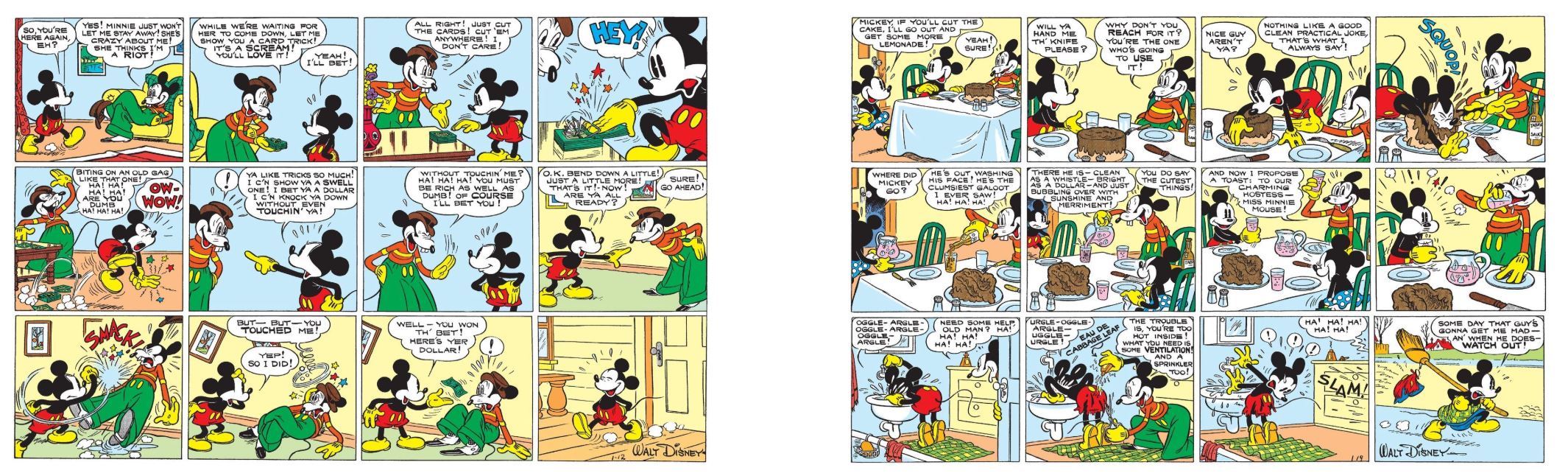

Essay ‘Growing Up, Growing Down’ leads to a sequence demonstrating Mickey’s gifts as ‘The Ventriloquist’ (11th October – 8th November) with Gottfredson & Taliaferro limning another Osborne extended script with the rascally rodent exhibiting his voice throwing gifts – and puckish sense of prankery – to Pluto, Goofy, Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow before inevitably suffering a major reversal of fortune…

Many, many more ‘Gag Strips’ follow (November 15th 1936 to May 9th 1937) as Osborne, Gottfredson, Thwaites & Taliaferro carry readers into a new year and beyond with slapstick hijinks about injury, infirmity, house, garden and motorcar maintenance, domestic spats, pets, circuses, playing practical jokes, and inescapable retaliation, pickpockets, panhandling, and snow. Bad weather, hunting and jail figure heavily too, as does love, with charmed simpleton Goofy’s unique point of view increasingly making Mickey the straight man in an enduring new relationship.

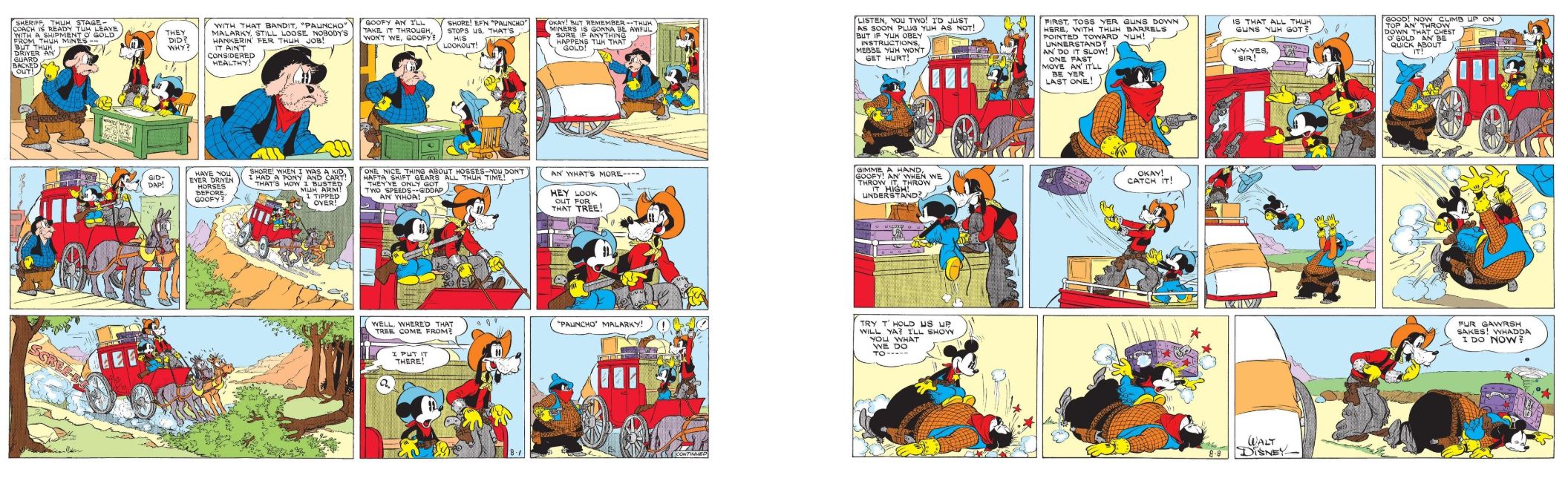

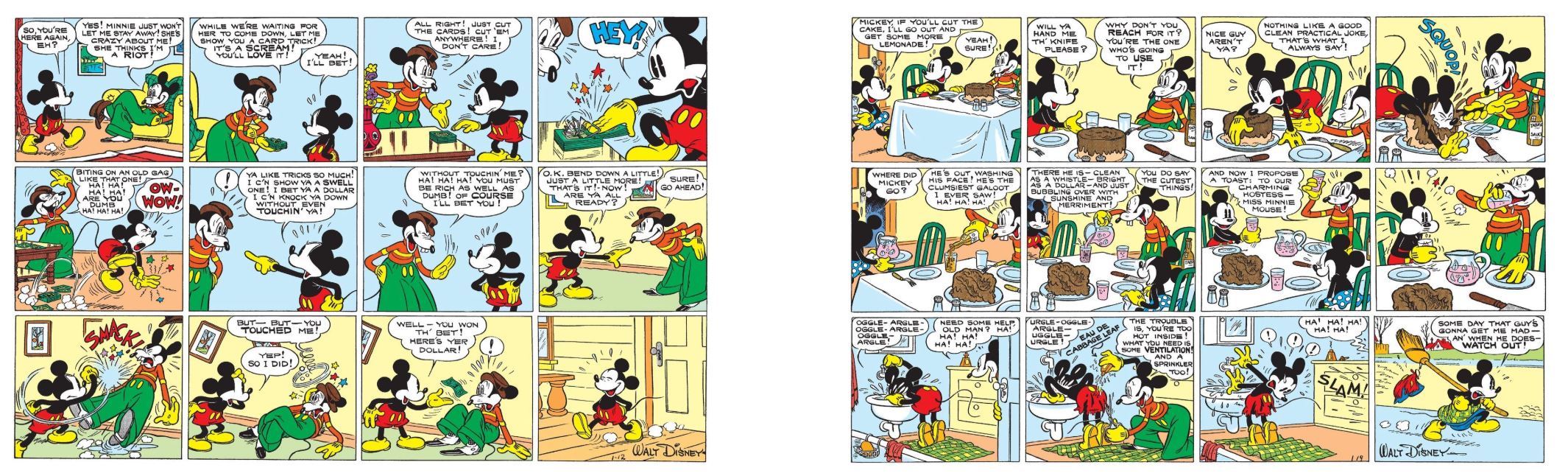

Halting momentarily to enjoy a Gottfredson private commission of the Mouse in cowboy mode from the 1980s, this compilation then heads west, only pausing to absorb more background and context via Francisco Stajano & Leonardo Gori’s essay ‘The Good, the Bad, and the Sunday’ Then Osborne scripts another gem for sagebrush devotee Gottfredson and inker Taliaferro in ‘Sheriff of Nugget Gulch’, running from May 16th to October27th. Here over-enthusiastic tenderfeet (tenderfoots?) Mickey & Goofy take a holiday of sorts after Minnie informs them of a gold strike near her uncle’s ranch. Sadly en route to Nugget Gulch, their rowdy excitement convinces everyone that they are deadly gunslingers: the toughest desperadoes since the Dalton Gang and both faster on the trigger than Bill Hickock…

The comedy of errors fully unfolds as the utterly unproven reputations of “Big Poison” & “Little Poison” continues to mount, with bandits pre-emptively heading for the hills and a terrified populace making them the new lawmen. Sadly that doesn’t count for much with genuine bad seed Pauncho Malarky, but eventually justice, goodness and blind luck carry the day and the railroad carries our heroes home…

Palate cleansing ‘Gag Strips’ from Osborne, Gottfredson, Thwaites & Taliaferro sustained readers between October 31st 1937 and 27th February 1938, with favoured themes like car trouble, house repairs, fancy dress, fashion, crop harvesting, bug infestation, family illness (Minnie’s nephew Manfred), construction crises and plain old surreal slapstick situations. Thanks to time of year, snow ice and inclement weather proved to timeless and reliable standbys, as were street crime, obnoxious cops and neighbours and household chores, with Minnie’s other rapscallion nephews (Mortimer and Ferdinand – AKA Morty & Ferdie – Fieldmouse) increasingly becoming the voice and faces of wayward youth in sneaky revolt…

Preceded by Gori & Stajano’s lecture ‘With Friends Like These’ continued sequence ‘Service with a Smile’ spans March 6th to April 10th with Merrill De Maris scripting for Gottfredson, Taliaferro, Manuel Gonzales & Thwaites. Her Mickey briefly manages his uncle’s gas service station, and between dealing with the public decides to go after delinquent clients and outstanding bills – with disastrous consequences. That chaos neatly transits to another tranche of stand-alone ‘Gag Strips’ (April 17th – August 21st 1938) by De Maris, Gottfredson, Taliaferro, Gonzales & Thwaites encompassing, bed-making, house cleaning, museum visits with Morty & Ferdie, fence-building with Goofy, hat-hunting with Minnie, more neighbour nonsense, car buying, chore-dodging, aviation antics, pet shenanigans and picnicking. As always many of these result in jail time – especially for Goofy and Mickey…

Another momentary diversion offers a Gottfredson inspired Goofy pinup/poem by Bob Grant from Mickey Mouse Magazine #59 (1940) comes in advance of movie inspired madness and mayhem again preceded by an essay. Thad Komorowski’s ‘Tailoring a Better Mouse’ explores Mickey’s declining film fanbase in lieu of rising stars Donald, Pluto & Goofy and how the Disney Studio remedied that with a new movie epic, suitably tied in and promoted to Gottfredson’s still hale and hearty newspaper strip. Albeit now a feature primarily supervised by Floyd and handled by Manual Gonzales, the strip actually saw print before the cinematic release of Brave Little Tailor.

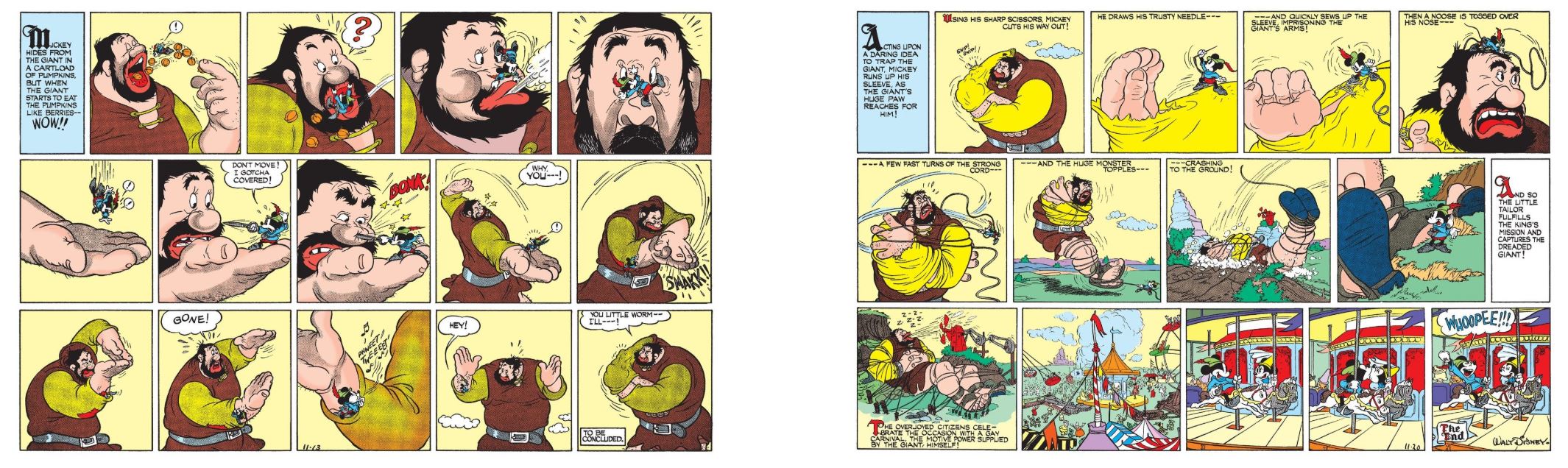

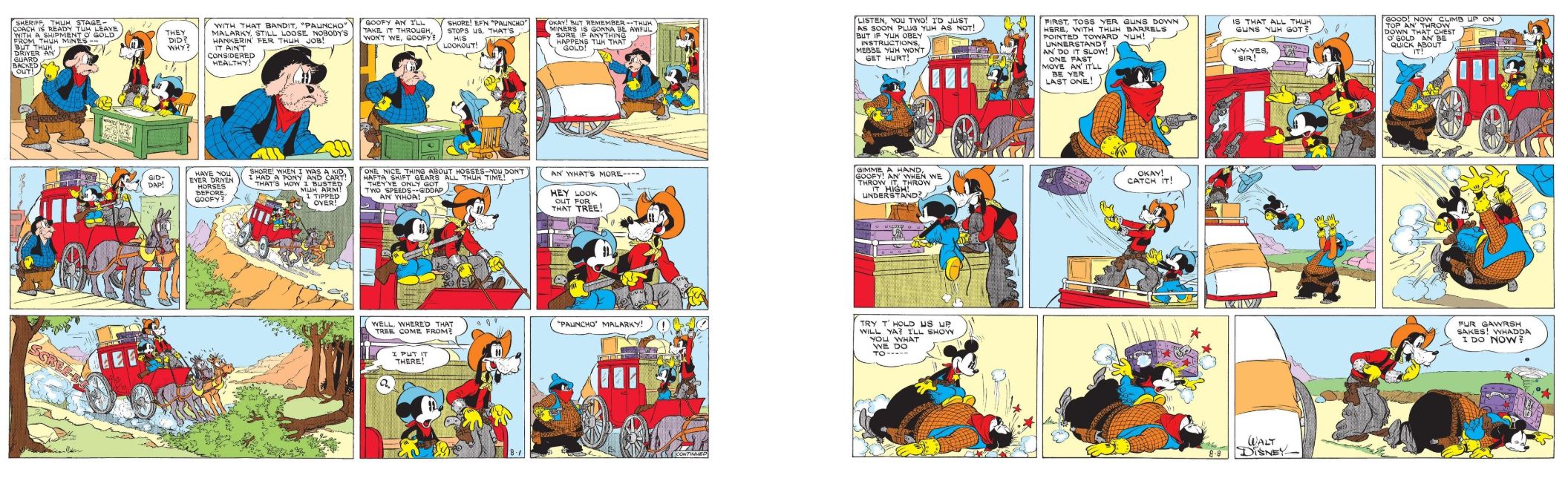

Running from August 28th to November 27th 1938, ‘The Brave Little Tailor’ began and ended with original framing episodes written by De Maris, who also adapted the film’s script which was realised by Gottfredson & Gonzales & inked by Thwaites. Here actor Mickey Mouse joins an epic in production and the fairy tales immediately becomes utterly real, as out unassuming hero is swept along in a rush to kill a giant, marry a princess and save an embattled kingdom…

De Maris, Gottfredson, Gonzales & Thwaites stuck around to produce more ‘Gag Strips’ spanning December 4th to 25th 1938, involving the film’s premier and Goofy’s growing prominence after which Gottfredson’s involvement was curtailed by his promotion to manager of the prodigious Comic Strip Department, addressed here in Later Years: Gottfredson Fill-Ins (June 17th 1956- September 19th 1976), through essay ‘Mouse Soup’. From the end of 1938, Gottfredson oversaw Gonzales on the Sunday feature until the mid-1940s when he gifted Frank Reilly with his managerial duties and took on “Special Projects”.

The period lasted until his retirement in 1976 and is represented here with a selection of delightful oddments beginning with more ‘Gag Strips’ starring a far more sedate and suburban Mouse and traversing June 17th 1956 to September 19th 1976, with stories by Bill Walsh, Roy Williams, & Del Connell, and pencilled and/or inked by Floyd with Tony Strobl. The content is lovely but no longer in any way subversive: detailing swimming pool and gardening woes, ice cream parlor perils, entertaining bored kids, sports, decorating, fashion, camping, pets… and snow…

The remainder of the comics content concerns other Disney stalwarts graced by the master storyteller’s touch. ‘Gottfredson Guest Stars: Donald Duck and Treasury of Classic Tales’ shows stories of other Disney strip features and comes with its own briefing in context confirming ‘Calling All Characters!’ From there it’s a small hop to ‘Donald Duck Gag Strips’ by Osborne, Taliaferro & Gottfredson as seen in the Silly Symphonies feature for October 3rd & 10th 1937. Here the mad as heck mallard goes hunting with Pluto as his gun dog and deeply regrets pranking Goofy with a peashooter…

Walt Disney’s Treasury of Classic Tales extended and adapted other studio screen gems and Gottfredson lustrated many of them, beginning here with Frank Reilly’s interpretation of ‘Lambert the Sheepish Lion’ which ran from August 5th to September 30th 1956. It’s followed by ‘The Seven Dwarfs and the Witch Queen’ (March 2nd – April 27th, 1958) with Gottfredson writing and lettering a saga illustrated by Julius Svensden. The team reunited for the film adaptation of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ from August 3rd to December 28th 1958, and Gottfredson’s last hurrah here was laying out Reilly’s adaptation of ‘101 Dalmatians’ (January 1st to March 26th 1961) for pencillers Bill Wright & Chuck Fuson. The eclectic but buzzy result was inked by Wright & Gonzales.

The joyous cartoon fun is complimented by another mini-moment: this one discussing the rarely seen pre-US Mickey Mouse Sunday strips published in Britain’s Sunday Pictorial from July 13th 1930, and how they never should have been released at all…

Although the comics conclude here there’s still plenty to see and learn as The Gottfredson Archives: Essays and Special Features section follows with a plethora of picture packed articles. Kicking off is ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Mickey’s Rival and Helpless Helpers’ with overseas edition depicting ratty rogue Mortimer as seen in Italy’s Topolino and Germany’s Mickey Maus Mini-Comic Klassiker, with ‘The Cast: Mortimer’ by Gerstein giving a full assessment of the love-rat before segueing into the expert’s review of Otto Englander’s film storyboards of a most influential unfinished epic in ‘Behind the Scenes: Interior Decorators (Again!)’.

A Gottfredson painting offers visual refreshment in ‘Mickey Mouse Adventures with Robin Hood Adventure’ prior to ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: The Robin Hood Adventure’ sharing international interpretations of the tale from Yugoslavia, Italy and Brazil. Then Gerstein appraises recycled Earl Hurd storyboards in ‘Behind the Scenes: Mickey’s Garden’, whilst ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Gags of 1936-1938’ depicts international collections of the auteur’s single page strips published in the US and Italy, before Gerstein deconstructs ‘The Inventive Goof’ and Alberto Becattini & Gerstein share the story of a late arriving collaborator in ‘Sharing the Spotlight: Julius Svensden’.

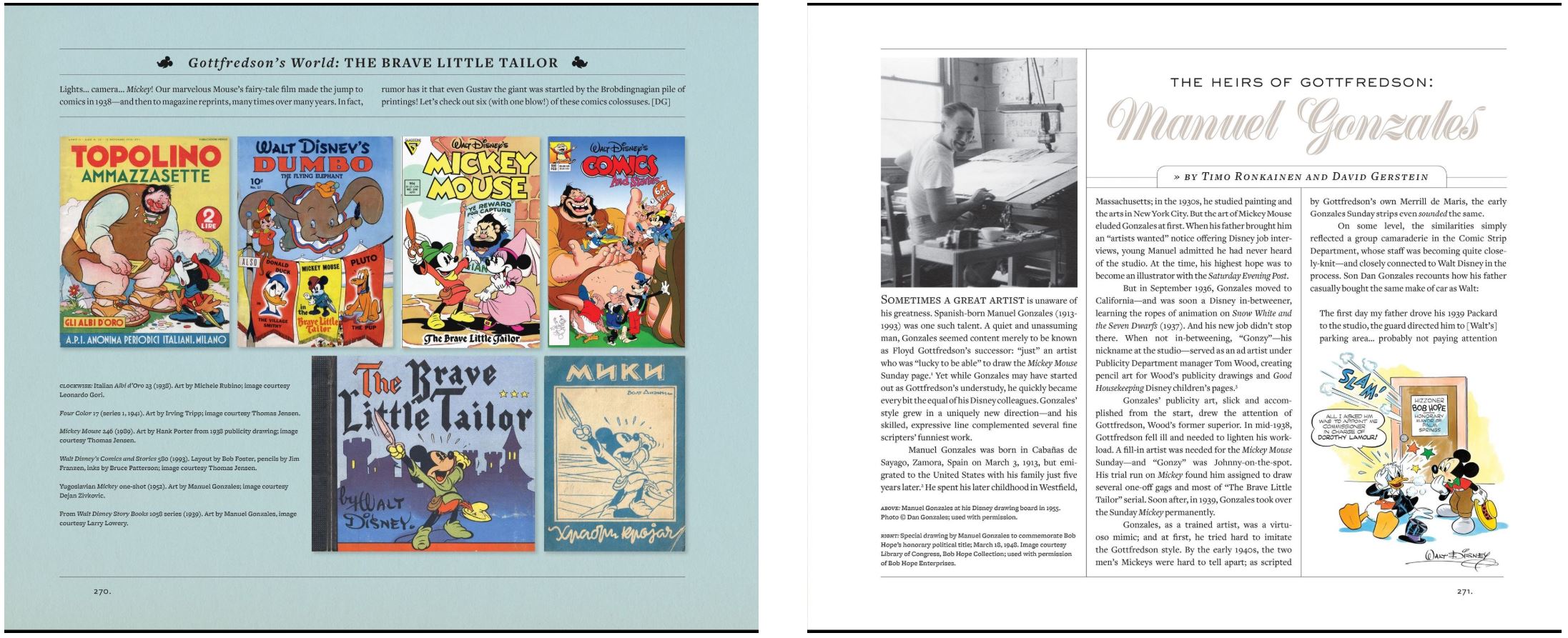

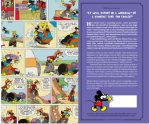

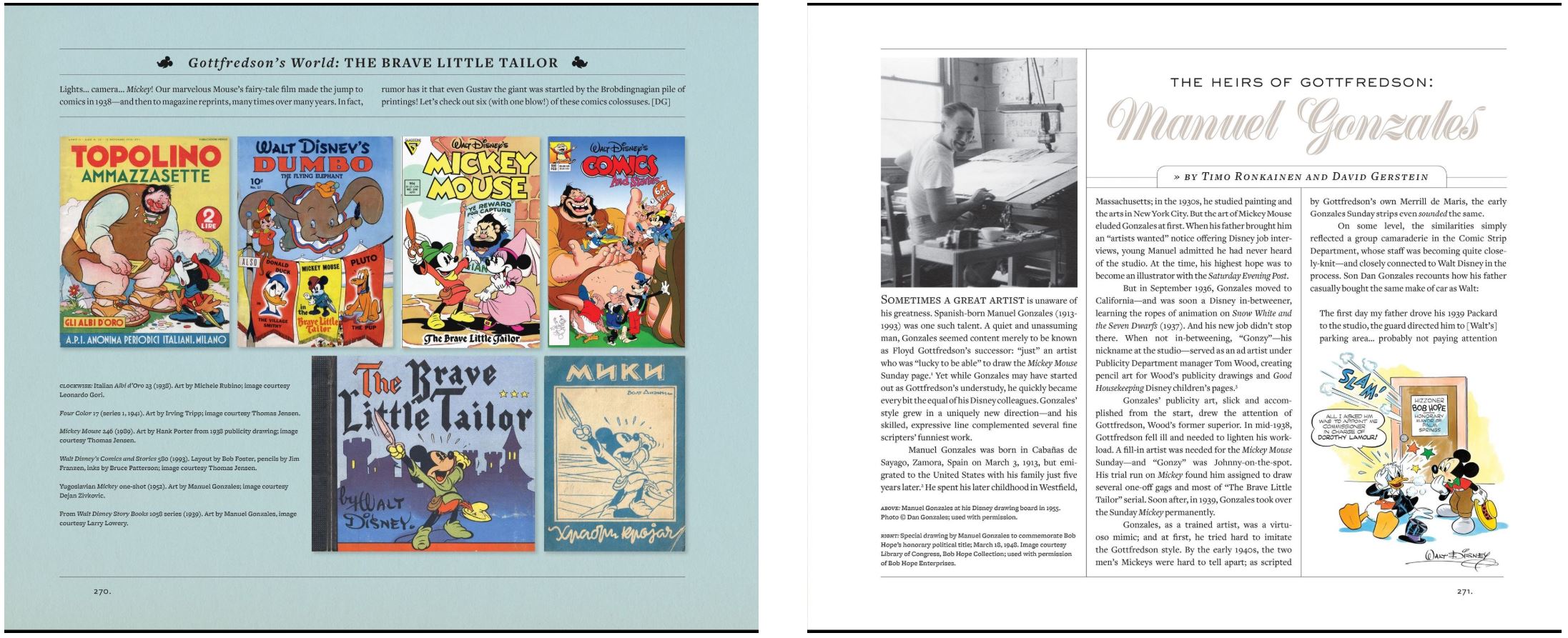

Fully focused on cowboy fun ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Sheriff of Nugget Gulch’ depicts some of the numerous compilations of the western classic from America and France, whilst six versions from Italy, the US and Yugoslavia illuminate a follow up ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: ‘The Brave Little Tailor’. Then Timo Ronkainen & Gerstein again highlight a Mickey mainstay in ‘The Heirs of Gottfredson: Manuel Gonzales’ before a last dose of strip silliness comes via Gag Strips (A Mickey Supplement): selections from August 25th 1940 to 18th February 1951 by De Maris, Walsh, Gonzales, and Wright.

The glee finally stops with a lovely sketch from Floyd entitled ‘Al [Taliaferro] came into the studio…’, a pertinent cover from California Magazine and biographies of the hard-working editors involved on this splendid tome…

Floyd Gottfredson’s influence on not just Disney’s canon but sequential graphic narrative itself is inestimable: he was among the very first to produce long continuities and “straight” adventures, pioneered team-ups and invented some of the art form’s first “super-villains”.

When Disney killed their continuities in 1955, dictating henceforth strips would only contain one-off gags, Floyd adapted seamlessly, working until retirement in 1975. His last daily appeared on November 15th with the final Sunday included here published on September 19th 1976.

Like all Disney’s creators, Gottfredson worked in utter anonymity, until, in the 1960s, his identity was revealed and the roaring appreciation of previously unsuspected hordes of devotees led to interviews, overviews and public appearances, leading to subsequent his reprinting in books, comics and albums which now all carried a credit for the quiet, reserved master. Floyd Gottfredson died in July 1986.

Thankfully we have these Archives to enjoy, inspiring us and hopefully a whole new generation of inveterate tale-tellers.…

Still, isn’t there more we could find for a third book?

Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Color Sundays volume 2 “Robin Hood Rides Again” © 2013 Disney Enterprises, Inc. Text of “Mickey’s Sunday Best: Moving On” by J.B. Kaufman is © 2013 by J.B. Kaufman. Text of “Of Blots and Stressed-Out Bodies” by Tom Neely is © 2013 by Tom Neely. All contents © 2013 Disney Enterprises unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.