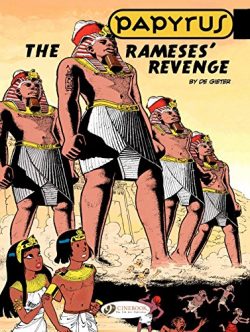

By Lucien De Gieter, translated by Luke Spear (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-1- 905460-35-9

British and European Comics have always been keener on historical strips than our American cousins, and the Franco-Belgian contingent in particular have made an art form out of combining the fascinations of past lives with drama, action and especially broad humour in a genre uniquely suited to beguiling readers of all ages and tastes.

Papyrus is the astoundingly addictive magnum opus of Belgian cartoonist Lucien de Gieter. Launched in 1974 in legendary weekly Le Journal de Spirou, it eventually ran to 35 collected albums and spawned a wealth of merchandise, a TV cartoon series and video games.

De Gieter was born in Etterbeek, Belgium on September 4th 1932 and, after attending Saint-Luc Art Institute in Brussels, worked as an industrial designer and interior decorator before moving into comics in 1961.

Initially he worked on inserts (fold-in half-sized-booklets known as ‘mini-récits‘) for Spirou, such as the little cowboy Pony, and produced scripts for established Spirou creators such as Kiko (Roger Camille), Jem (Jean Mortier), Eddy Ryssack and Francis (Bertrand). He then joined Peyo’s (Pierre Culliford) studio as inker on Les Schtroumpfs – which you’ll know as The Smurfs – and soloed as latest creator on long-running newspaper comic cat strip Poussy.

After originating mermaid strip T̫̫̫t et Puit in 1966 and seeing Pony graduate to the full-sized pages of Spirou in 1968, De Gieter relinquished his Smurfs gig, but kept himself busy producing work for Le Journal de Tintin and Le Journal de Mickey. From 1972-1974 he assisted Flemish cartooning legend Arthur Berckmans (AKA Berck) on comedy science-fiction series Mischa for the German Rolf Kauka Studios anthology magazine Primo, whilst preparing the serial which would occupy his full attention Рas well as that of millions of avid fans Рfor the next four decades.

The annals of Papyrus encompass a huge range of themes and milieu; mixing Boy’s Own adventure with historical fiction, fantastic action and interventionist mythology. The enthralling Egyptian epics gradually evolved from standard “Bigfoot†cartoon style and content to a more realistic, dramatic and authentic iteration. Each tale also deftly incorporated the latest historical theories and discoveries into the beguiling yarns.

Papyrus is a fearlessly forthright young fisherman favoured by the gods who rises against all odds to become an infallible champion and friend to Pharaohs. As a youngster the plucky Fellah (peasant or agricultural labourer, fact fans) was singled out and given a magic sword courtesy of the daughter of crocodile-headed Sobek before winning similar boons and blessings from many of the Twin Land’s potent pantheon.

The youthful champion’s first accomplishment was liberating supreme deity Horus from imprisonment in the Black Pyramid of Ombos and restoring peace to the Double Kingdom, but it was as nothing compared to his current duties: safeguarding Pharaoh’s wilful, high-handed and insanely danger-seeking daughter Theti-Cheri – a dynamic princess with an astounding knack for finding trouble …

The Rameses’ Revenge is actually the seventh collected album, originally released on the Continent in 1984 as La Vengeance des Ramsès and finds Papyrus en route to the newly finished temple at Abu-Simbel on a royal barge; part of a vast flotilla destined to commemorate the magnificent Tomb of Rameses II.

Although his sedate Nile journey is plagued with frightful dreams, great friend and companion Imhotep tells him not to worry. Nevertheless, the boy hero dutifully consults a priest and is deeply worried when the sage declares the dreams are a warning…

That tension only grows when headstrong, impatient Theti-Cheri informs him that she has permission to go on ahead of the Pharaoh’s retinue in a small, poorly-armed skiff. Unable to dissuade her, Papyrus is furious when she imperiously orders him to remain behind. As they set off, the Princess and Imhotep are blissfully unaware that a member of her small guard has been replaced by a sinister impostor…

The vessel is well underway before they discover Papyrus has stowed away, but before the furious girl can have him thrown overboard, the boat is hit by an implausibly sudden storm and attacked by a pair of monsters.

Although boy hero Papyrus valiantly drives them away with his sword, Theti-Cheri sees nothing, having been knocked out in the storm. Still seething, she refuses to believe him or Imhotep and orders the expedition onward to Abu-Simbel. The next morning Papyrus and the guards are missing…

Pressing on anyway, the Princess and her remaining attendants reach the incredible edifice only to be seized by the band of brigands who have captured it. They want the enormous treasure hidden within the sprawling complex and already hold Papyrus prisoner.

If Theti-Cheri or the hostage Temple Priests won’t hand over the booty, the boy will die horribly…

The repentant Princess cannot convince the clerics to betray their holy vows, however, and in desperation declares that she will surrender herself instead. Appalled and moved by her noble intention, High Priest Hapu determines that only extreme measures can avenge the bandits’ sacrilegious insult and calls on mighty Ra to inflict the vengeance of the gods upon them…

The astounding, spectacular, terrifying result perfectly concludes this initial escapade and will thrill and delight lovers of fantastic fantasy and bombastic adventure.

Papyrus is another superb addition to the all-ages pantheon of continental champions who combine action and mirth with wit and charm, and even though UK publisher Cinebook haven’t released a new adventure since The Amulet of the Great Pyramid in 2015, anybody who has worn out their cherished Tintin, Spirou and Fantasio, Lucky Luke and Asterix collections would be well rewarded by checking out the six epic volumes still available (in paperback or eBook editions) and even harassing the publishers to start translating the rest of the fantastic canon…

© Dupuis, 1984 by De Gieter. All rights reserved. English translation © 2007 Cinebook Ltd.