By Robert Crumb and Charles Crumb (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-0-93019-343-0 (HB vol 1) 978-0-93019-362-8 (TPB vol 1)

ISBN: 978-0-93019-373-7(HB vol 2) 978-0-93019-362-1 (TPB vol 2)

These books employ Discriminatory Content for comedic and dramatic effect.

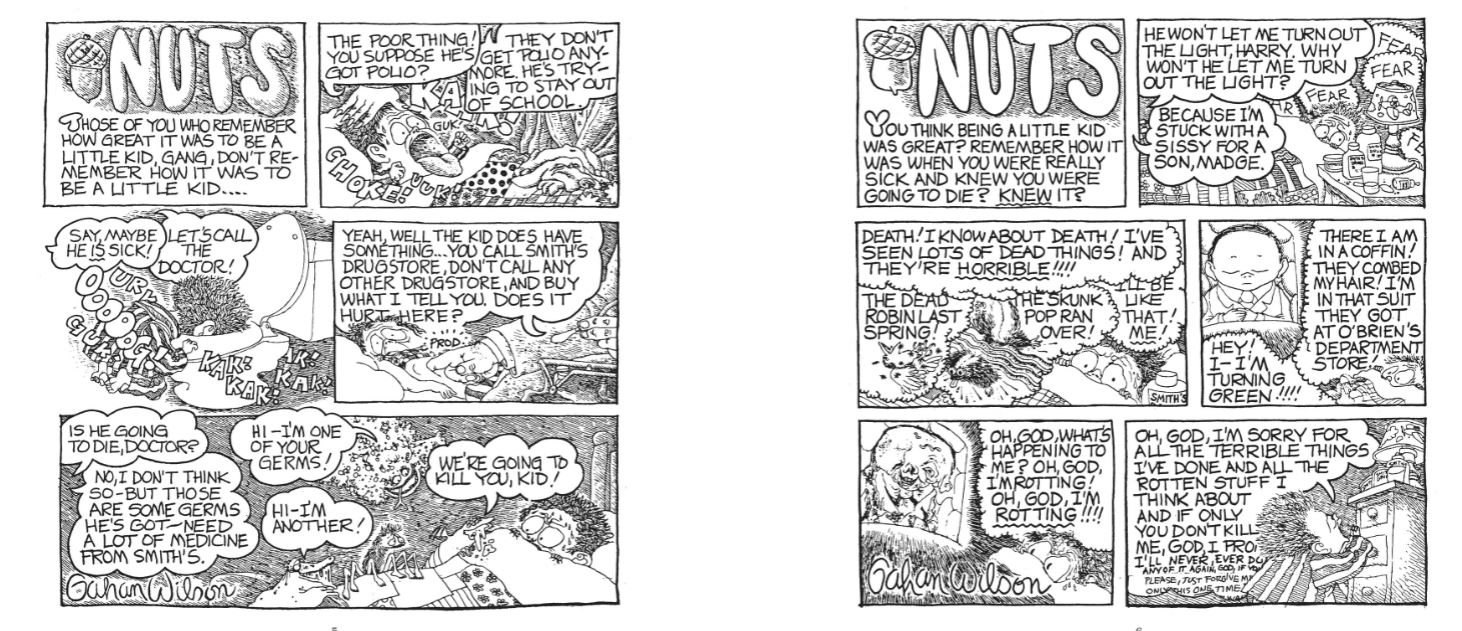

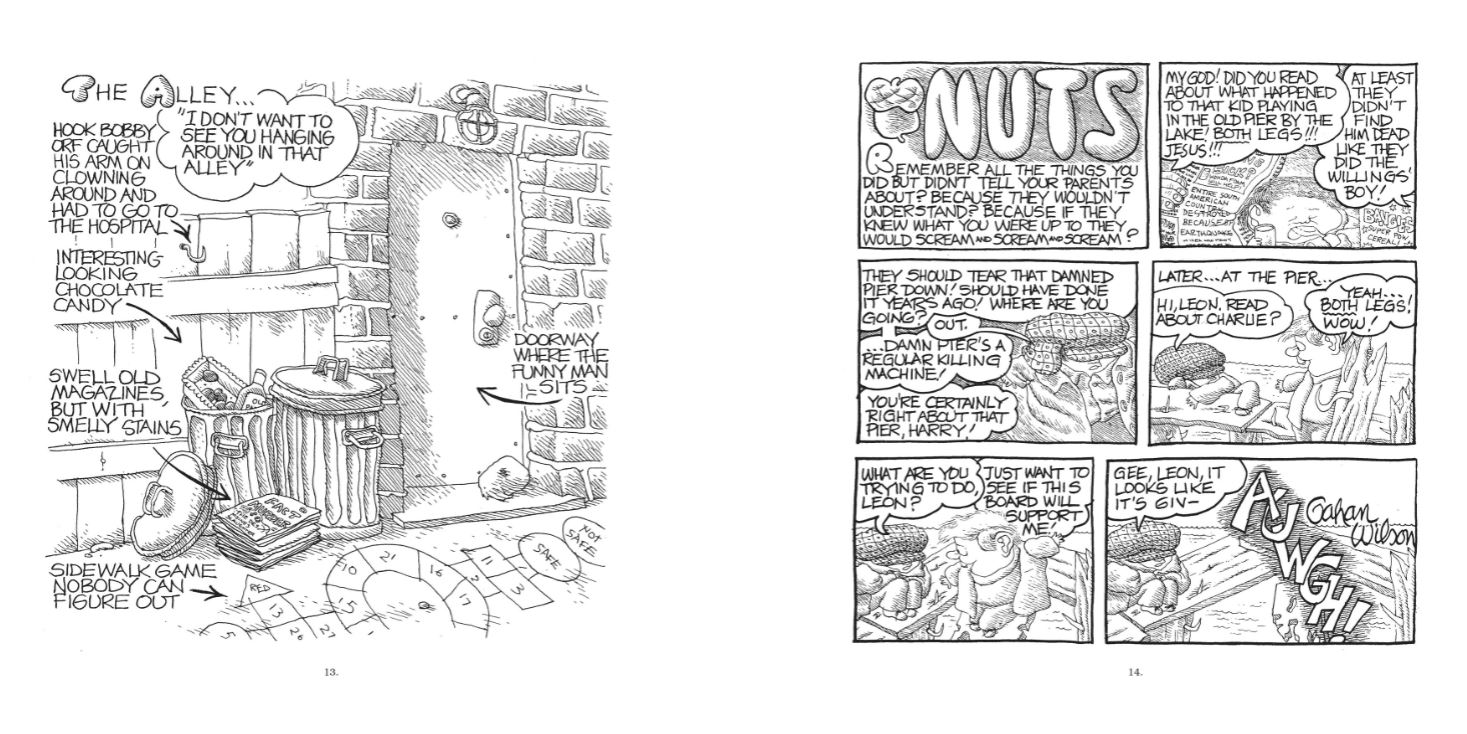

Immensely divisive but a key figure in the evolution of comics as an art form, Robert Crumb was born today 81 years ago. He is a unique creative force in the world of cartooning with as many detractors as devotees. His uncompromising, excoriating, neurotic introspections, pictorial rants and invectives unceasingly picked away at societal scabs and peeked behind forbidden curtains for his own benefit, but he has always happily shared his unwholesome discoveries with anybody who takes the time to look. Last time I looked, he’s still going strong…

In 1987 Fantagraphics Books began the nigh-impossible task of collating, collecting and publishing the chronological totality of the artist’s vast output. The earliest volumes have been constantly described as the least commercial and, as far as I know, remain out of print, but contrary as ever, I’m reviewing them anyway before the highly controversial but inarguably art-form enfant terrible/bête noir/shining hope finally puts down his pens forever. A noted critic of Donald Trump, he might well be hanging on just for the sheer satisfaction of outliving ol’ Taco-scabby paws…

The son of a career soldier, Robert Dennis Crumb was born in Philadelphia in 1943 into a functionally broken family. He was one of five kids who all found different ways to escape their parents’ shattering problems and comics were always paramount amongst them.

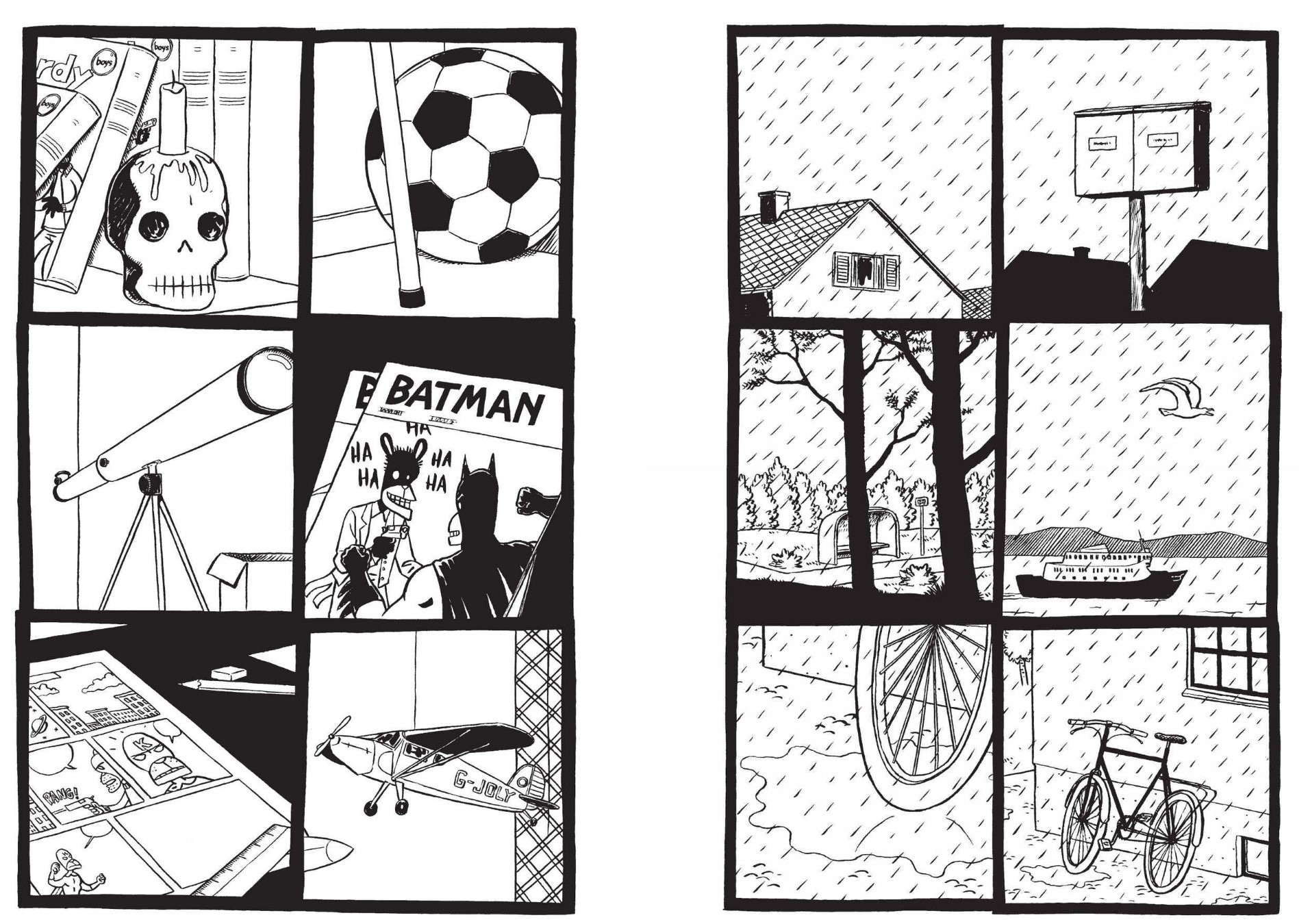

As had his older brother Charles, Robert immersed himself in strips and cartoons of the day; not simply reading but feverishly creating his own. Harvey Kurtzman, Carl Barks and John Stanley were particularly influential, but so were newspaper artists like E.C. Segar, Gene Ahern, Rube Goldberg, Bud (Mutt and Jeff) Fisher, Billy (Barney Google), De Beck, George (Sad Sack) Baker and Sidney (The Gumps) Smith, as well as illustrators like C.E. Brock and the wildly imaginative and surreal 1930’s Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies animated shorts.

Defensive and introspective, young Robert pursued art and slavish self-control through religion with equal desperation. His early spiritual repression and flagrant, hubristic celibacy constantly warred with his body’s growing needs…

Escaping a stormy early life, he married young and began working in-house at the American Greeting Cards Company. He discovered like minds in the growing counterculture movement and discovered LSD. In 1967 Crumb relocated to California to become an early star of Underground Commix. As such he found plenty of willing hippie chicks to assuage his fevered mind and hormonal body whilst reinventing the very nature of cartooning with such creations as Mr. Natural, Fritz the Cat, Devil Girl and a host of others. The rest is history…

Those tortured formative years provide the meat of first volume The Early Years of Bitter Struggle, which, after ‘Right Up to the Edge’ – a comprehensive background history and introduction from lifelong confidante Marty Pahls – begins revealing the troubled master-in-waiting’s amazingly proficient childhood strips from self-published Foo #1-3 (a mini-comic project passionately produced by Robert and older brother Charles from September to November 1958).

Rendered in pencils, pens and whatever else was handy; inextricably wedded to those aforementioned funnybooks, strips and animated shorts cited above, the mirthful merry-go-round opens with ‘Report From the Brussels World’s Fair!’ and ‘My Encounter With Dracula!’: frantic, frenetic pastiches of the artists’ adored Mad magazine material, with Robert already using a graphic avatar of himself for narrative purposes. Closely following are the satirical ‘Clod of the Month Award’, ‘Khrushchev Visits U.S.!!’ and ‘Noah’s Ark’.

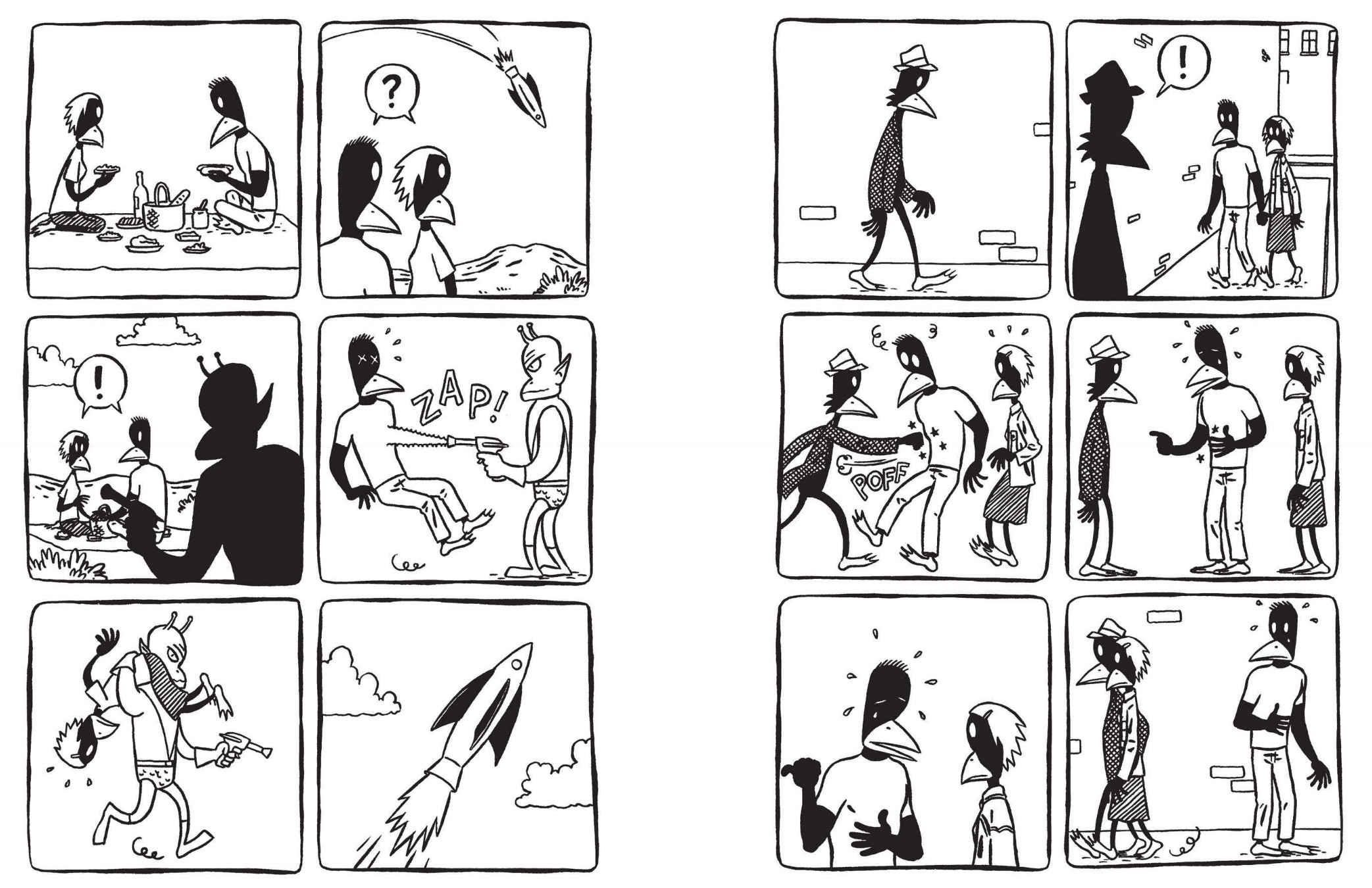

From 1959, ‘Treasure Island Days’ is a rambling gag-encrusted shaggy dog Russian Roulette experiment created by the lads each concocting a page and challenging the other to respond and continue the unending epic, after which ‘Cat Life’ followed family pet Fred’s fanciful antics from September 1959 to February 1960 before morphing (maybe “anthropomorphing”) into an early incarnation of Fritz the Cat in ‘Robin Hood’…

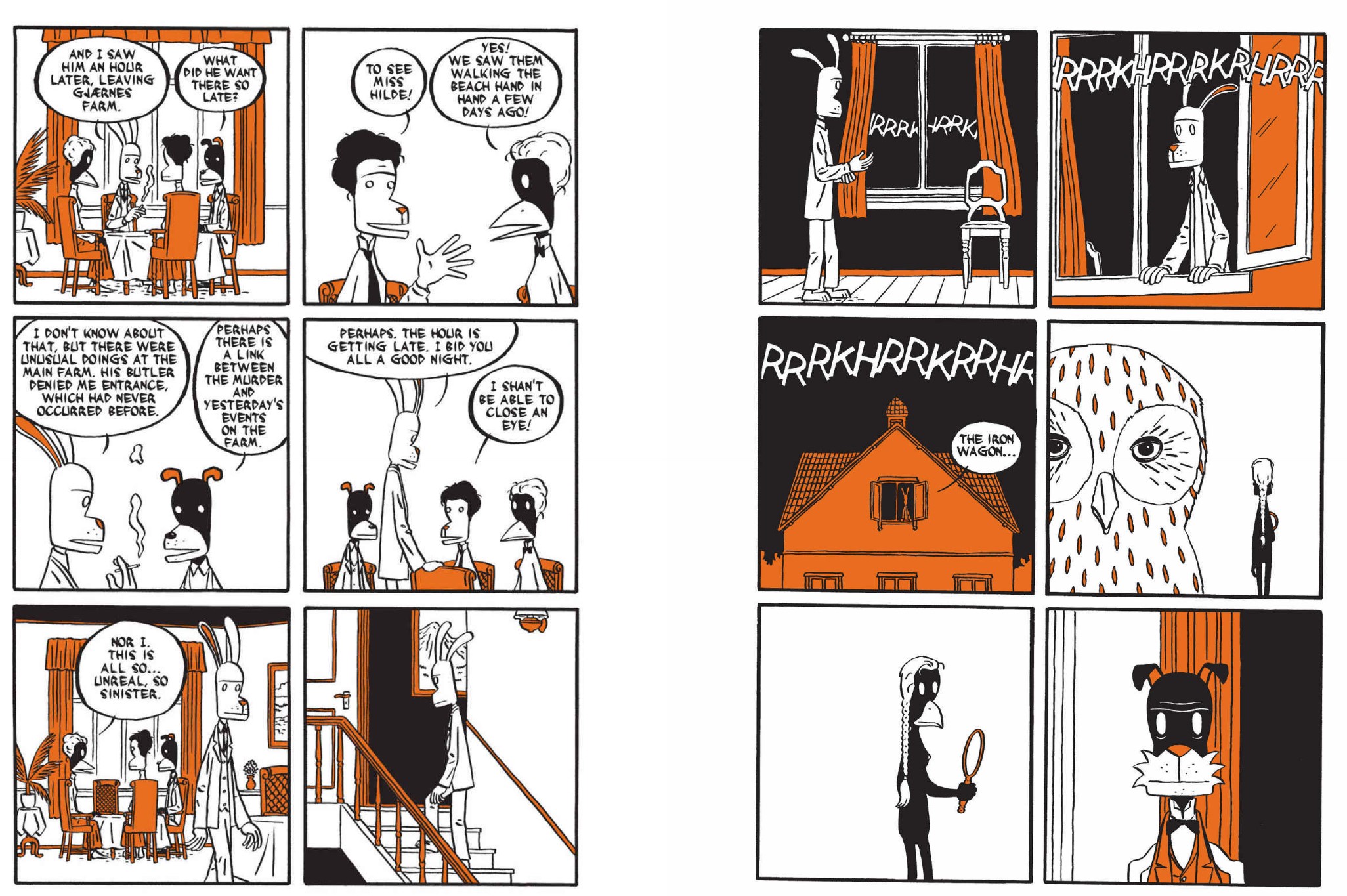

That laconic stream of cartoon-consciousness resolved into raucous, increasingly edgy saga ‘Animal Town’ followed here by a very impressive pin-up ‘Fuzzy and Brombo’, before a central full-colour section provides a selection of spoof covers. Four ‘R. Crumb Almanac’ images – all actually parts of letters to Pahls – are complemented by three lovely ‘Arcade’ covers, swiftly followed by a return to narrative monochrome and ‘A Christmas Tale’ which saw Crumb’s confused and frustrated sexuality begin to assert itself in his still deceptively mild-mannered work.

A progression of 11 single-page strips produced between December 1960 – May 1961 precedes 3 separate returns to an increasingly mature and wanton ‘Animal Town’ – all slowly developing the beast who would become Crumb’s first star, until Fritz bows out in favour of ‘Mabel’ – a prototypical big and irresistible woman of the type Crumb would legendarily have trouble with – before this initial volume concludes with another authorial starring role in the Jules Feiffer/Explainers-inspired ‘A Sad Comic Strip’ from March 1962.

Second volume Some More Early Years of Bitter Struggle continues the odyssey after another Pahls reminiscence – ‘The Best Location in the Nation…’ describes a swiftly maturing deeply unsatisfied Crumb’s jump from unhappy home to the unsatisfying world of work. ‘Little Billy Bean’ (April 1962) returns to the hapless, loveless nebbish of ‘A Sad Comic Strip’ whilst ‘Fun with Jim and Mabel’ revisits Crumb’s bulky, morally-challenged amazon prior to focus shifting to her diminutive and feeble companion ‘Jim’.

Next, an almost fully-realised ‘Fritz the Cat’ finally gets it on in a triptych of saucy soft-core escapades from R. Crumb’s self-generated Arcade mini-comic project. From this point on, the varied and exponentially impressive breadth of Crumb’s output becomes increasingly riddled with his frequently hard-to-embrace themes and declamatory, potentially offensive visual vocabulary as his strips grope towards a creator’s long-sought personal artistic apotheosis.

His most intimate and disturbing idiosyncrasies regarding sex, women, ethnicity, personal worth and self-expression all start to surface here…

Therefore, if intemperate language, putative blasphemy, cartoon nudity, fetishism and comedic fornication are liable to upset you or those legally responsible for you, stop reading this review right here and don’t seek out the book.

Working in the production department of a vast greetings card company gave the insular Crumb access to new toys and new inspiration as seen in the collection of ‘Roberta Smith, Office Girl’ gag strips from American Greetings Corporation Late News Bulletins (November 1963 – April 1964), followed here by another Fritz exploit enigmatically entitled ‘R. Crumb Comics and Stories’ which includes just a soupcon of raunchy cartoon incest, so keep the smelling salts handy…

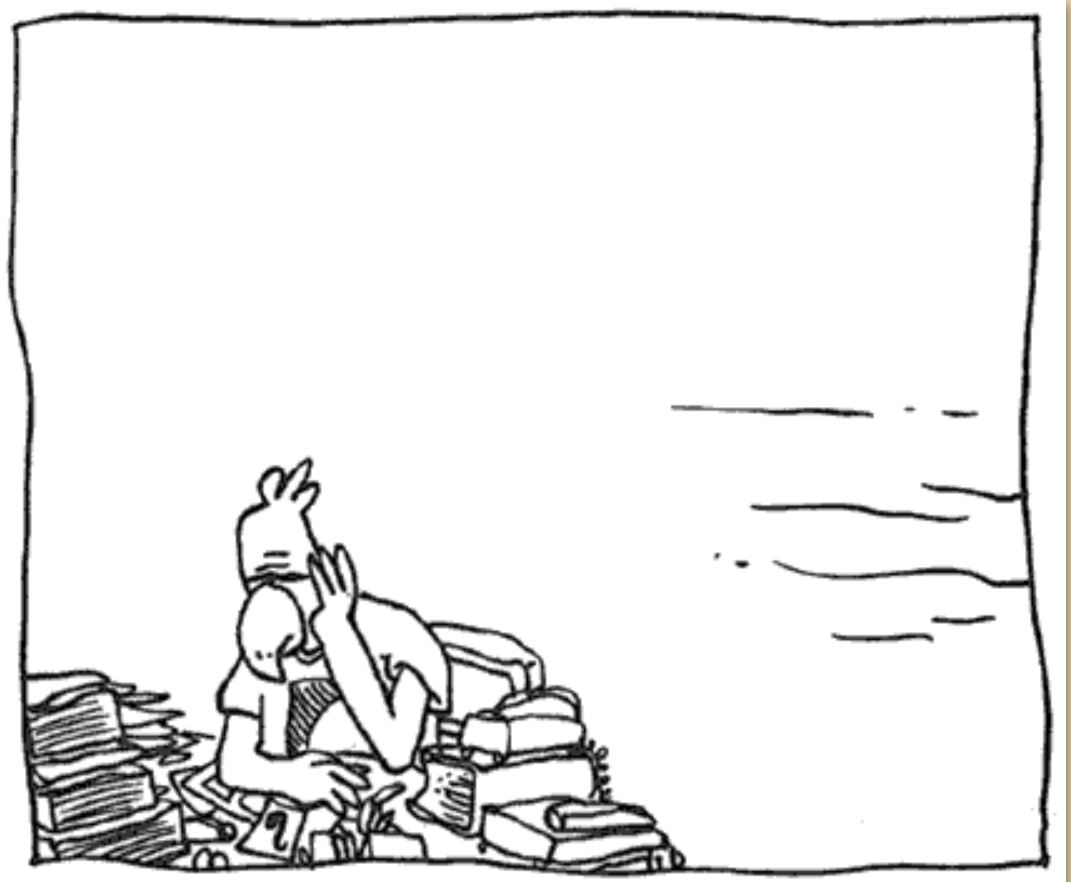

A selection of beautiful sketchbook pages comes next and a full-colour soiree of faux covers: letters to Pahls and Mike Britt disguised as ‘Farb’ and ‘Note’ front images as well as a brace of Arcade covers and the portentously evocative front of R. Crumb’s Comics and Stories #1 from April 1964. The rest of this pivotal collection is given over to 30 more pages culled from the artist’s sketchbooks: a vast and varied compilation ably displaying Crumb’s incredible virtuosity and proving that if he had been able to suppress his creative questing Robert could easily have settled for a lucrative career in any one of a number of graphic disciplines from illustrator to animator to jobbing comic book hack.

Crumb’s subtle mastery of his art form and obsessive need to expose his most hidden depths and every perceived defect – in himself and the world around him – has always been an unquenchable fire of challenging comedy and riotous rumination, and these initial tomes are the secret to understanding the creative causes, if not the artistic affectations of this unique craftsman and auteur.

This superb series charting the perplexing pen-and-ink pilgrim’s progress was the perfect vehicle to introduce any (over 18) newcomers to the world of grown up comics. And if you need a way in yourself, seek out these books and the other fifteen as soon as conceivably possible. Or, just perhaps, Fantagraphics could unleash them all again and include digital editions for these artistic pearls of immeasurable price…

Report From the Brussels World’s Fair!, My Encounter With Dracula!, Clod of the Month Award, Khrushchev Visits U.S.!! & Noah’s Ark © 1980 Robert and Charles Crumb. Other art and stories © 1969, 1974, 1978, 1987, 1988 Robert Crumb. All rights reserved.