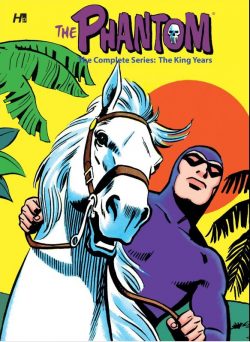

By Bill Harris, Dick Wood & Bill Lignante, Giovanni Fiorentini & Senio Pratesi & various (Hermes Press)

ISBN: 978-1-61345-009-3

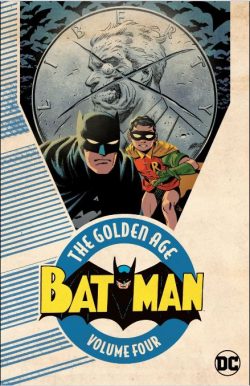

In the 17th century a British sailor survived an attack by pirates, and, washing ashore in Africa, swore on the skull of his murdered father to dedicate his life and that of all his descendants to destroying all pirates and criminals. The Phantom fights crime and injustice from a base deep in the jungles of Bengali, and throughout Africa is known as the “Ghost Who Walksâ€.

His unchanging appearance and unswerving quest for justice have led to him being considered an immortal avenger by the credulous and the wicked. Down the decades one hero after another has fought and died in an unbroken family line, and the latest wearer of the mask, indistinguishable from the first, continues the never-ending battle…

Lee Falk created the Jungle Avenger at the request of his syndicate employers who were already making history, public headway and loads of money with his first strip sensation Mandrake the Magician…

Although technically not the first ever costumed hero in comics, The Phantom was the prototype paladin to wear a skin-tight body-stocking and the first to have a mask with opaque eye-slits.

He debuted on February 17th 1936 in an extended sequence that pitted him against a global confederation of pirates called the Singh Brotherhood. Falk wrote and drew the daily strip for the first two weeks before handing over the illustration side to artist Ray Moore. The Sunday feature began in May 1939.

For such a successful, long-lived and influential series, in terms of compendia or graphic novel collections, The Phantom has been very poorly served by the English language market.

Various small companies have tried to collect the strips – one of the longest continually running adventure serials in publishing history – but in no systematic or chronological order and never with any sustained success.

But, even if it were only of historical value (or just printed for Australians, who have long been manic devotees of the implacable champion) surely “Kit Walker†is worthy of a definitive chronological compendium series?

Happily, his comic book adventures have fared slightly better – at least in recent times…

Between 1966 and 1967 King Features Syndicate dabbled with a comicbook line of their biggest stars – Flash Gordon, Mandrake and The Phantom – developed after the Ghost Who Walks had enjoyed a solo-starring vehicle under the broad and effective aegis of veteran licensed properties publisher Gold Key Comics.

The Phantom was no stranger to funnybooks, having been featured since the Golden Age in titles such as Feature Book and Harvey Hits, but only as straight reformatted strip reprints. The Gold Key exploits were tailored to a big page and a young readership, a model King maintained for their own run.

This splendid full-cover hardcover – or eBook for the modern minded – gathers the contents of The Phantom #19-28 (originally released between November 1966 and December 1967) as well as four back-up vignettes from Mandrake #1-4, spanning September 1966 to January 1967.

Following fascinating Introduction ‘The Phantom, the King Years’ from fans and scholars Pete Klaus and Howard S. Gesbeck (which includes some splendid unseen art and candid photos) the procession of classic wonders resumes.

As with the Gold Key issues, the majority of the stories are scripted by Bill Harris or Dick Wood and drawn in comicbook format by Bill Lignante, with cover by or based on images from the daily strip as limned by Sy Barry.

Opening the King archive is a fabulously wry romp as a coterie of crooks inveigles their way into the Phantom’s jungle home, intent on stealing ‘The Treasure of the Skull Cave’. Over the centuries the Ghost Who Walks has amassed the most fantastic hoard of legendary loot and astounding artefacts, but the trio of crooks can’t agree on what is or isn’t valuable and soon pay the price for their folly and genocidal intent…

Issue #19 tapped into the global excitement as America neared its first manned moonshots with ‘The Astronaut and the Pirates’ finding the Phantom hunting the seagoing brigands who abduct and ransom an American spaceman after his off-course splashdown lands him in very hot water…

The second tale in the issue relies on more traditional themes as ‘The Masked Emissary’ intervenes in a civil war; protecting an ousted democratic leader from a tyrannical despot, until liberty can be restored to the people.

The Phantom #20 – cover dated January 1967 – led with a bold departure from tradition. Scripted by Pat Fortunato ‘The Adventures of the Girl Phantom’ delved into the meticulous family chronicles to reveal how, a few generations previously, the feisty twin sister of a former Ghost Who Walked took her brother’s place to police the jungles of Bengali after he was laid low.

Counterpointing that radical drama is a moody mad science thriller as the current masked marvel battles old enemy Dr. Krazz and aliens from the Earth’s interior in ‘The Invisible Demon’…

In #21 ‘The Treasure of Bengali Bay’ finds the Phantom battling bandits using their own fake ghost to secure sunken loot after grudge-bearing Indian Prince Taran lures our hero to the sub-continent as fodder for specially trained animal assassin ‘The Terror Tiger’.

Full-length drama ‘The Secret of Magic Mountain’ pits The Immortal Avenger against sly witch doctor Tuluck who mixes misconceived ancient history and a freshly-active volcano to turn the local tribes against The Phantom, whilst in #23 merciless pirate ‘Delilah’ takes the place of a Peace Corps worker to get lethally close to the guardian of the jungle.

However, her devious wiles, brainwashing techniques and super-submarine prove of little use against the dauntless and implacable Ghost Who Walks…

Girl Phantom Julie steals the show again in #24 as she and faithful friend Maru challenge the forces of darkness to defeat a vicious manipulator in ‘The Riddle of the Witch’…

Writer Giovanni Fiorentini and illustrator Senio Pratesi tackle #25 as the modern hero and famous athlete and sportswoman (and prospective wife) Diana Palmer frustrate slave-taking diamond smugglers intent on subjugating ‘The Cold Fire Worshippers’ before issue #26 marks a return to double story instalments.

Lignante’s ‘The Lost City of Yiango’ sees the Phantom compelled to solve a 50-year old mystery and prevent a resurgence of tribal warfare, after which he answers a desperate plea to safeguard an irreplaceable treasure and goes undercover to thwart ‘The Pearl Raiders’…

The Phantom #27 reveals the origins of the African Avenger’s wonder-horse as ‘The Story of Hero’ discloses how he once rescued kidnapped Princess Melonie of Kabora and how – following ‘The Long Trip Home’ – he was thanked with a most marvellous equine gift…

The Phantom’s King chronicles concluded in #28 ‘Diana’s Deadly Tour’ as the celebrity embarks on a global exhibition jaunt and is targeted by ruthless spies. Not only must her enigmatic paramour keep her safe but also solve the bewildering mystery of why they keep trying to kill her…

Wrapping up the issue is an ultra-short yarn as a frustrated world champion boxer hunts the Ghost Who Walks determined to prove who’s the toughest guy in ‘The Big Fight’…

As mentioned above the Phantom guested in vignettes in Mandrake #1-4. Those ‘Back-Up Stories’ round out the comics cavalcade here beginning with ‘SOS Phantom’ as the Guardian Ghost responds to secret drum signals to quell an outbreak of fever, whilst ‘SOS Phantom: The Pirate Raiders’ finds him answering similar “threat tomtoms†to tackle and terrify superstitious coastal raiders…

Those self-same drums are crucial in thwarting a murderous criminal mastermind intent on penning the Phantom in ‘The Magic Ivory Cage’ and the flurry of little epics ends with another outing for ‘The Girl Phantom’ who here outwits a brutal strongman whose brawn and belligerence are no match for cool head…

Sprinkled liberally with original art, unused cover designs for the never-printed issues #29 and 30, examples from foreign editions and a wealth of original art pages by Jim Aparo (from forthcoming volume The Phantom: The Complete Series: The Charlton Years: volume 1) this another nostalgia drenched triumph: straightforward, captivating rollicking action-adventure that has always been the staple of comics fiction.

If that sounds like a good time to you, this is a traditional action-fest you can’t afford to miss…

The Phantom® © 1966-1967 and 2012 King Features Syndicate, Inc. ® Hearst Holdings, Inc. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.