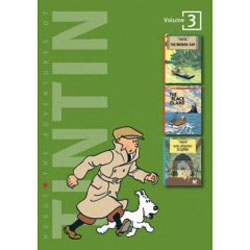

By Hergé, translated by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper & Michael Turner (Egmont UK)

ISBN 13: 978-1-4052-2897-8

Hergé was approaching his mastery when he began The Broken Ear: His characterisations were firm in his mind, he was creating a memorable not to say iconic supporting cast, and the balance between crafting satisfactory single instalments and building a cohesive longer narrative was finally being established.

The version reprinted in this delightfully handy hardback compendium was repackaged by the artist and his studio in 1945, although the original ran in two page weekly instalments from 1935-1937, and there are still evident signs of his stylistic transition in this hearty, exotic mystery tale that makes Indiana Jones look like a boorish amateur.

Back from China, Tintin hears of an odd robbery at the Museum of Ethnography, and rushing over finds the detectives Thompson and Thomson already on the case in their own unique manner. A relatively valueless carved wooden Fetish Figure made by the Arumbaya Indians has been taken from the South American exhibit. Bafflingly, it was returned the next morning, but the intrepid boy reporter is the first to realise that it’s a fake, since the original statue had a broken right ear. And a minor sculptor is found dead in his flat…

So begins a frenetic and enthralling chase to find not just who has the real statue but also why a succession of rogues attempts to secure the dead sculptor’s parrot, with the atmospheric action encompassing the urban metropolis, an ocean-going liner and the steamy and turbulent Republic of San Theodoros, where the valiant lad becomes embroiled in an on-again, off-again Revolution. Eventually though, the focus moves to the deep Jungle as Tintin finally meets the Arumbayas and a lost explorer, getting one step closer to solving the mystery.

Whilst unrelenting in my admiration for Hergé I must interject a necessary note of praise for translators Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner here: Their light touch has been integral to the English-language success of Tintin, and their skill and whimsy is never better seen than in their dialoguing of the Arumbayas. Just read aloud and think Eastenders…

The slapstick and mayhem build to a wonderfully farcical conclusion with justice served all around, and a solid template is set for many future yarns, especially those that would perforce be crafted without a political or satirical component during Belgium’s grim occupation by the Nazis.

However, Hergé’s developing social conscience and satirical proclivities are fully exercised here in a telling sub-plot when rival armaments manufacturers gull the leaders of both San Theodoros and its neighbour Nuevo-Rico into a war simply to increase their sales, and once again oil speculators would have felt the sting of his pen – if indeed they were capable of any feeling…

The Black Island followed. It ran from 1937-1938, (although this is the revised version released in 1956) and the doom-laden atmosphere that was settling upon the Continent even seeped into this dark tale of espionage and criminality. When a small plane lands in a field, Tintin is shot as he offers help. Visited in hospital by Thompson and Thomson, he discovers they’re en route to England to investigate the crash of an unregistered plane. Discharging himself and with Snowy in tow he catches the boat-train but is framed for an assault and becomes a fugitive. Despite a frantic pursuit he makes it to England, still pursued by the murderous thugs who set him up as well as the authorities.

He is eventually captured by the gangsters – actually German spies – and uncovers a forgery plot, which leads him to the wilds of Scotland and a (visually stunning) “haunted†castle on an island in a Loch. Undaunted, he investigates and discovers the gang’s base, which is guarded by a monstrous ape.

This superb adventure, powerfully reminiscent of John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, highlight the theme that as always virtue, pluckiness and a huge helping of comedic good luck lead to a spectacular and thrilling denouement.

Older British readers have reason to recall the final tale in this tome. Many of them had an early introduction to Tintin and his dog (then called Milou, as in the French editions) when the fabled Eagle comic began running King Ottokar’s Sceptre in translated instalments on their prestigious full-colour centre section in 1951. Originally created by Hergé in 1938-1939, this tale was one of the first to be revised (1947) when the political fall-out settled after the war ended.

Hergé continued to produce comic strips for Le Soir during the Nazi Occupation (Le Petit Vingtième, the original home of the strip was closed down by the Nazis), and in the period following Belgium’s liberation was accused of being a collaborator and even sympathiser. It took the intervention of Resistance hero Raymond Leblanc to dispel the cloud over Hergé, which he did by simply vouching for the cartoonist and by providing the cash to create the magazine Tintin which he published. The anthology comic swiftly achieved a weekly circulation in the hundreds of thousands.

The story itself is pure escapist magic as a chance encounter via a park-bench leads our hero on a mission of utmost diplomatic importance to the European kingdom of Syldavia. This picturesque Ruritanian ideal stood for a number of countries such as Czechoslovakia that were in the process of being subverted by Nazi insurrectionists at the time of writing.

Tintin becomes a surveillance target for the enemy agents and after a number of life-threatening near misses flies to Syldavia with his new friend. The sigillographer Professor Alembick is an expert on Seals of Office and his research trip coincides with a sacred ceremony wherein the Ruler must annually display the fabled sceptre of King Ottakar to the populace or lose his throne. When the sceptre is stolen it takes all of Tintin’s luck and cunning to prevent an insurrection and the overthrow of the country by enemy agents.

Full of dash, as compelling as a rollercoaster ride, this is classic adventure story-telling to match the best of the cinema’s swashbucklers and as suspenseful as a Hitchcock thriller, balancing insane laughs with moments of genuine tension. As the world headed into a new Dark Age, Hergé was entering a Golden one.

These ripping yarns for all ages are an unparalleled highpoint in the history of graphic narrative. Their constant popularity proves them to be a worthy addition to the list of world classics of literature.

The Broken Ear: artwork © 1945, 1984 Editions Casterman, Paris & Tournai.

Text © 1975 Egmont UK Limited. All Rights Reserved.

The Black Island: artwork © 1956, 1984 Editions Casterman, Paris & Tournai.

Text © 1966 Egmont UK Limited. All Rights Reserved.

King Ottokar’s Sceptre: artwork © 1947, 1975 Editions Casterman, Paris & Tournai.

Text © 1958 Egmont UK Limited. All Rights Reserved.