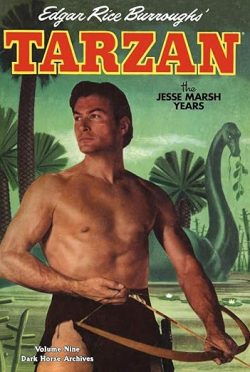

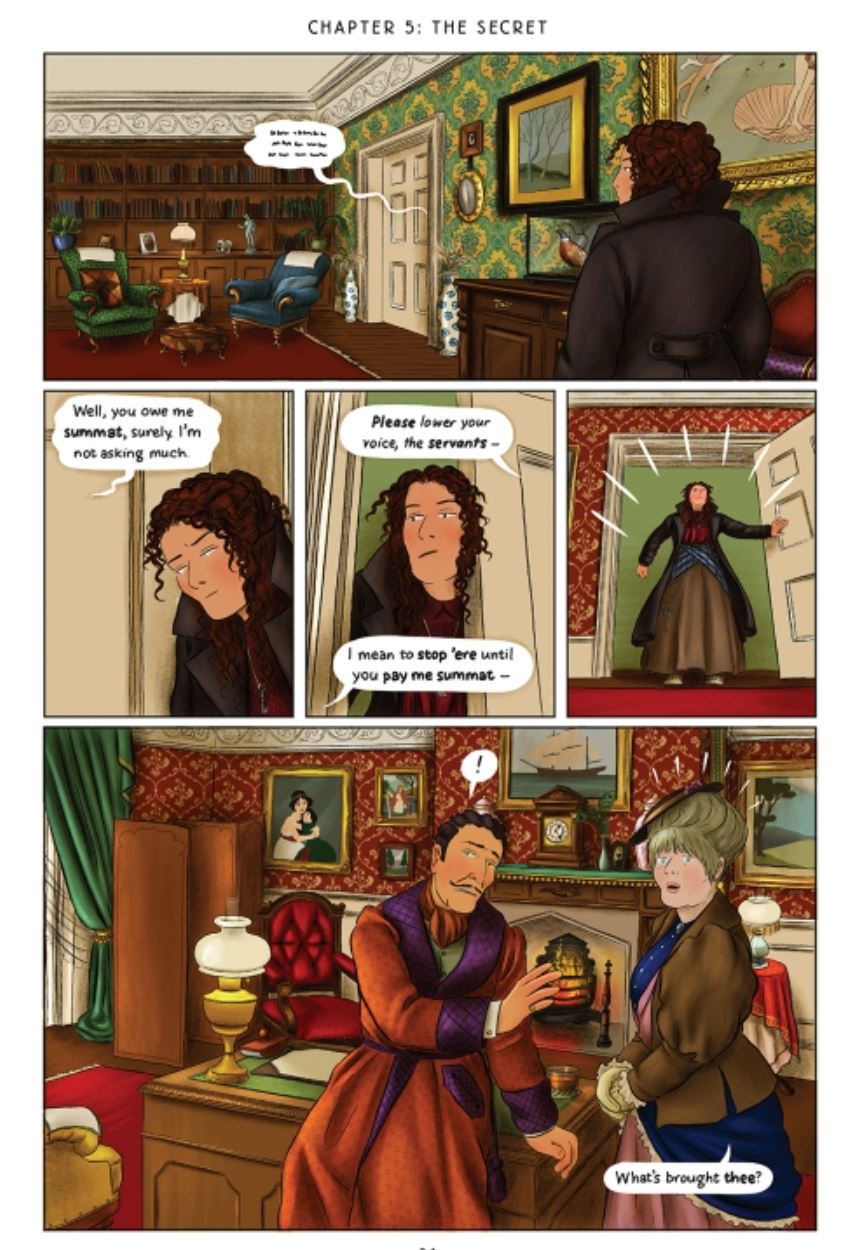

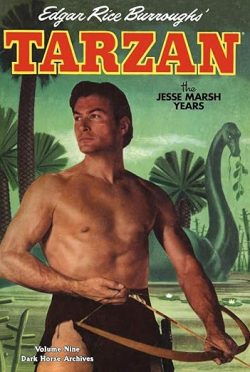

By Gaylord DuBois & Jesse Marsh (Dark Horse Books)

ISBN: 978-1-59582-649-7 (HB)

This book includes Discriminatory Content produced in less enlightened times.

Win’s Christmas Gift Recommendation: Primal fantasy Adventure… 8/10

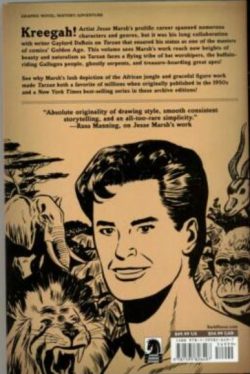

I don’t know an awful lot about Jesse Marsh, other than that he was born on 27th July 1907 and died far too young: on April 28th 1966 from diabetic complications at the height of a TV Tarzan revival he was in large part responsible for. What I do know, however, is that to my unformed, pre-fanboy, kid’s mentality, his drawings were somehow better than most of the other artists and that every other kid who read comics in my school disagreed with me.

There’s a phrase we used at 2000 AD that summed it up: “Artist’s artist”, which usually meant someone whose fan-mail divided equally into fanatical raves and bile-filled hate-mail. It seems there are some makers of comic strips that many readers simply don’t get.

It isn’t about the basic principles or artistic quality or even anything tangible – although you’ll hear some cracking justifications: “I don’t like his feet” (presumably the way he draws them) and “it just creeps me out” being my two favourites. Never forget in the 1980s DC were told by the Comics Code Authority that Kevin O’Neill’s entire style and manner of Drawing was unacceptable to American readers!

I got Jesse Marsh. He was another Disney animator (beginning in 1939) who moved sideways – in 1945 – to become a full-time narrative illustrator for the studio’s comic book licensee Whitman Publishing. Marsh never looked back and became the go-to guy for other ERB adaptations such as John Carter of Mars.

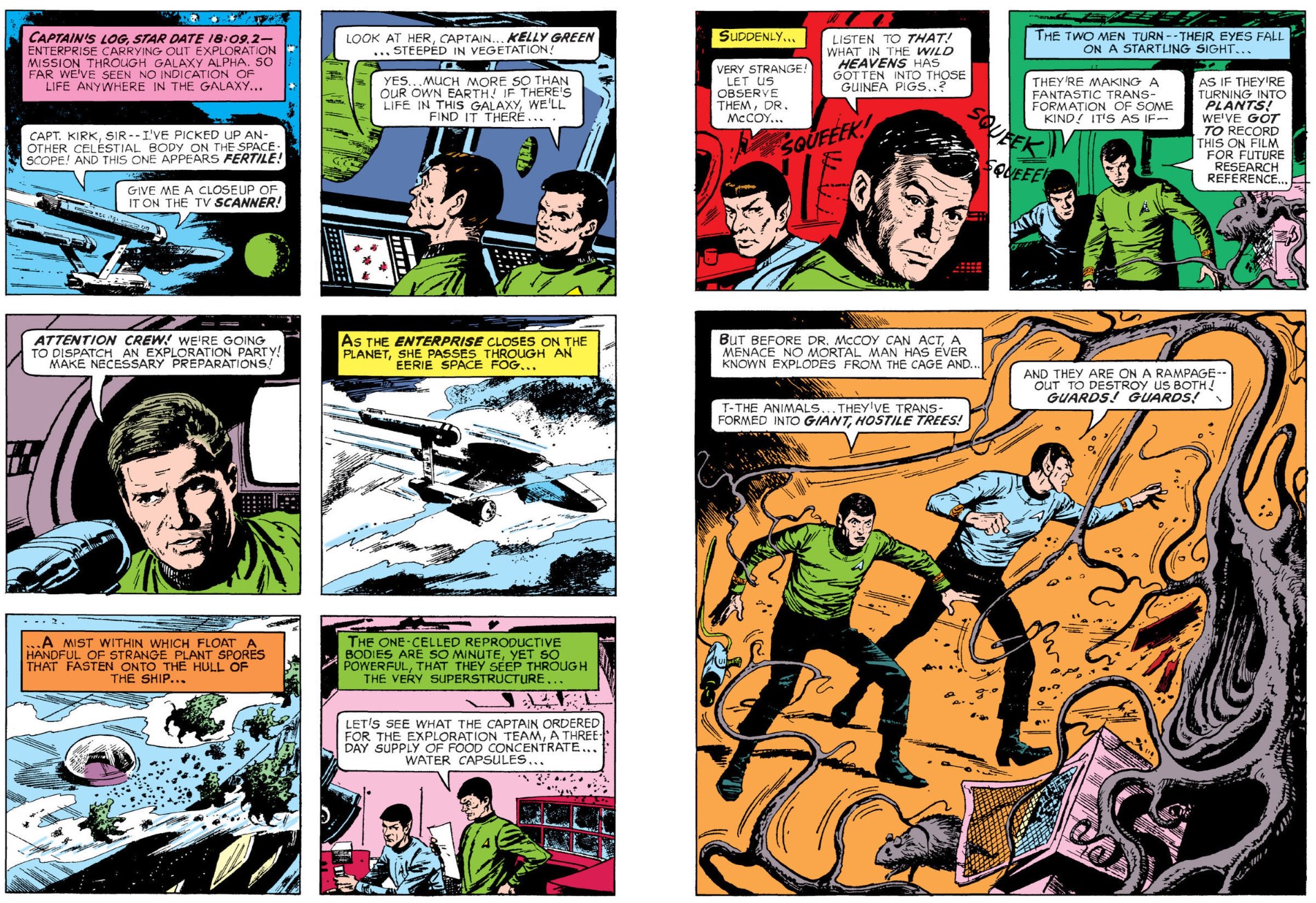

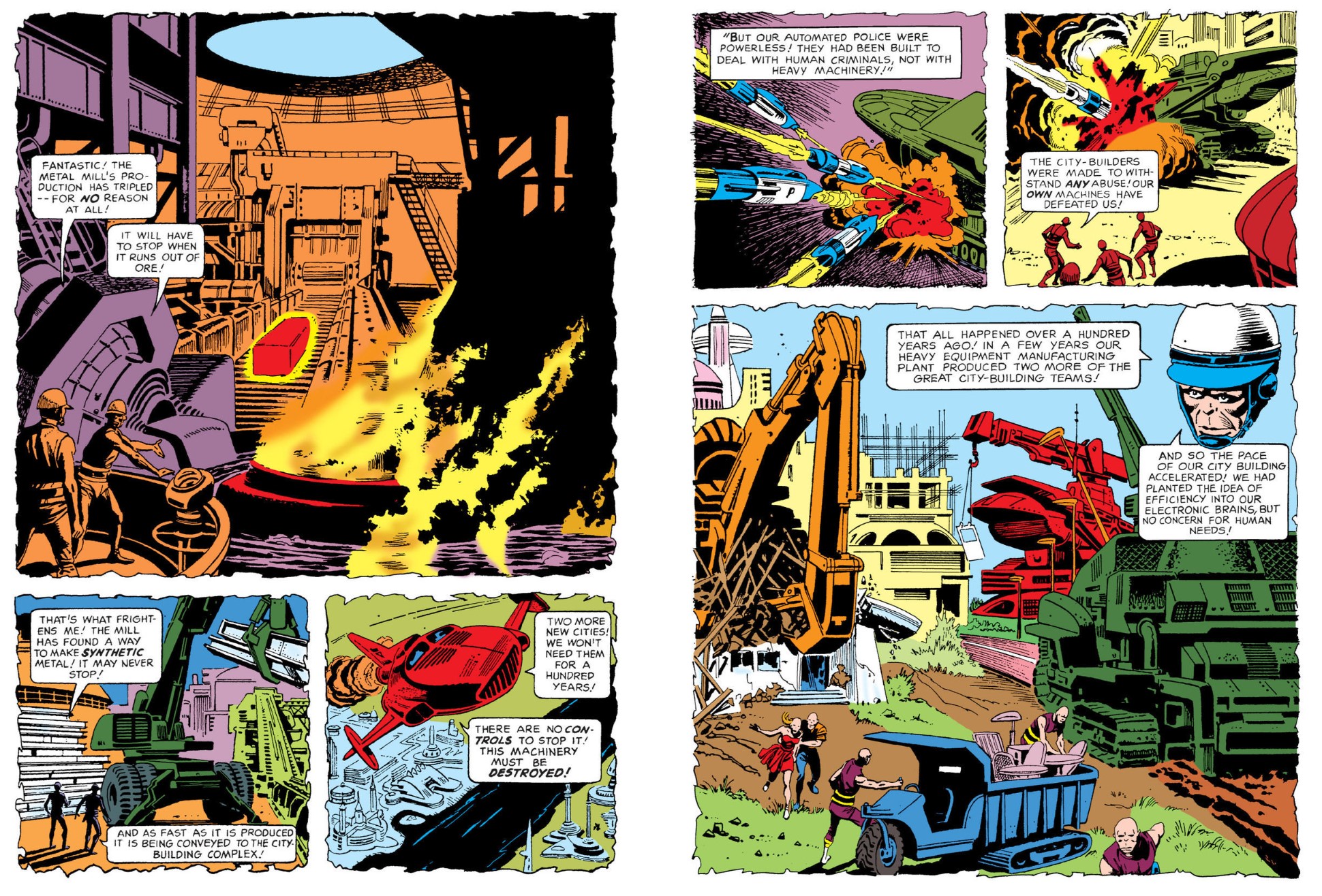

Situated on the West Coast, Western’s Dell/Gold Key imprints rivalled DC and Marvel at the height of their powers, and the licensee famously never capitulated to the wave of anti-comics hysteria that resulted in the crippling self-censorship of the 1950s. No Dell Comics ever displayed a Comics Code Authority symbol on the cover – they never needed to…

Marsh jobbed around adapted movie properties – mostly westerns like Gene Autry – until 1948 when Dell introduced the first all-new Tarzan comic book. The newspaper strip had run since 1929 and all previous funnybook releases had featured expurgated and modified reprints of those adventures. That all changed with Dell Four Color Comic #134 (February 1947) which featured a lengthy, captivating tale of the Ape-Man scripted by Robert P. Thompson, who also wrote both the Tarzan radio show and the aforementioned syndicated strip (as you can see in Tarzan and the Adventurers).

The comic was very much in the Burroughs tradition: John Clayton, Lord Greystoke and his friend Paul D’Arnot aid a young woman in rescuing her lost father from a hidden tribe ruled over by a monster. The engrossing yarn was made magical by the simple, underplayed magic of a heavy brush line and absolutely unmatched design sense. Marsh was unique in the way he positioned characters in space, using primitivist forms and hidden shapes to augment his backgrounds, and as the man was a fanatical researcher, his trees, rocks, and constructions were 100% accurate. His animals and natives, especially children and women, were all distinct and recognisable; not the blacked-up stock figures in grass skirts even the greatest artists so often resorted to.

He also knew when to draw big and draw small: the internal dynamism of his work is spellbinding. His Africa became mine, and of course the try-out comic book was an instant hit. Marsh and Thompson’s Tarzan returned with two tales in Dell Four Color Comic #161, cover-dated August 1947. This was a remarkable feat: Four Colour was a catch-all title showcasing in rotation literally hundreds of different licensed properties, often as many as ten separate issues per month. So rapid a return engagement meant pretty solid sales figures…

Bolstered by a healthy and extremely popular film franchise and those comics strips, within six months, bimonthly Tarzan #1 was released (January/February 1948). It was a swansong for Thompson, but another unforgettable classic for Marsh – and the first of an unbroken run that would last until 1965: over 150 consecutive issues. Moreover there were also spin-offs featuring other ERB character adaptations and gigantic specials like the Annual that opens this collected volume.

Prior to that, the collection – reprinting material from 1953 from Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan #44-46 and monumental bonus book Tarzan’s Jungle Annual #2 – opens with Foreword ‘Looking for Jesse Marsh’: a heartfelt appreciation and appraisal of the secretive genius by publisher Dan Nadel, packed with information about the enigmatic master. Then, cover-dated August 1953 and on sale from 16th July, that colossal bonus book delivers a painted cover by Morris Gollub (not featuring then current big screen Tarzan Lex Barker) in advance of a beguiling trip to an Africa that never was…

A monochrome Jungle World frontispiece revels in an idyllic quiet moment for the Ape-Man and faithful pachyderm pal Tantor, before main event ‘Tarzan in the Valley of Towers’ transports the Jungle Lord and pilot/scientist Professor Alexander MacWhirtle to a distant unexplored region in aid of a girl who sent a plea for help in a tiny parachute woven from spider-webs…

As always this yarn (and everything else including puzzles) was written by Gaylord DuBois. Editor and prolific scripter (Lone Ranger, Lost in Space, Turok, Son of Stone, Brothers of the Spear and many more) he was Marsh’s creative collaborator for nearly 20 years.

Flying into the great desert, Tarzan and “Professor Mac” soon find Heather Day laid out as a sacrifice on a towering limestone altar, left for giant carnivorous bats by debased humans who have turned themselves into flying/gliding predators in their image. The battle to overthrow the petty tyrants of the sky takes them from the highest peaks to deepest subterranean depths, but inevitably Tarzan triumphs and returns Hearther to the outer world.

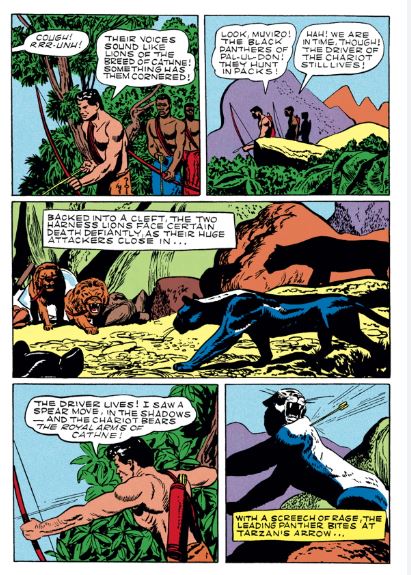

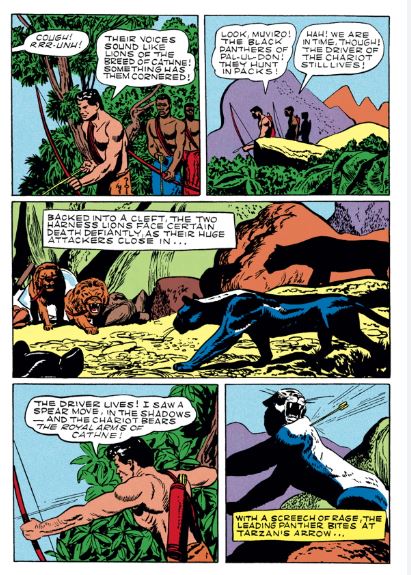

Back then, entertainment was full on and informative, so this Annual was packed with fact and activity features. First up, and still all Marsh in vision, is potted travelogue ‘Jungle Trails’ augmented by a simple method for ‘Making Maps’ and a clever rebus message from Tarzan to his ‘Jungle Village’. Then it’s back to action as ‘Tarzan and the Cannibals of Kando-Mor’ finds the Ape-Man and his Waziri friend Chief Muviro traversing the fearsome Great Swamp when the party is captured by man-eating men. Their escape brings the wanders fully into Burroughs’ rich fantasy-scape as they discover another isolated and embattled outpost of lost land Pal-Ul-Don (introduced in 8th novel Tarzan the Terrible) and befriend the buffalo-worshipping Gallugos. The event is quite timely as the ever-encroaching cannibals have almost completed their extended scheme to eliminate the cow-lovers…

Almost…

Illustrated sheet music provides long-distance lessons for ‘Dancing Feet’ to cavort at a ‘Moonlight Marriage’ ceremony, whilst ‘Happy Warrior’ shares the secrets of kite-making before ‘Boy Stands by a Friend’ offers another intimate peek at the formative years of Greystoke’s African family when Boy – later called Korak – and ape pal Zorok stow away on a riverboat and nearly end up as zoo exhibits. ‘Letters from Boy’ to the readers feature next, as ‘Jungle Hunt’ details how to make an inner tube popgun and water canteens, prior to an adventure with elephants as ‘The Troubles of Tantor’ seen the herd patriarch go to extraordinary lengths to rescue wayward calves captured by angry farmers.

Picture essays detail the secrets of MacWhirtle’s plane and the domain of dinosaurs in ‘Boys Air Adventure to the Valley of Monsters’ after which a touch of old-fashioned racial profiling describes native characteristics in ‘Jungle Tribes’ and ‘Jungle Woman’ before embracing romance as final story ‘Tarzan Trails the Brothers of the Barracuda’ sees the Ape-Man reunite shipwrecked and separated young lovers by hunting down the slave traders who have seized and sought to sell her…

Wrapping up with a load of lexicons, ‘Jungle Language: Swahili-English’ and ‘Jungle Language: Ape-English’ provides illustrated dictionaries that come in handy for the puzzle pages and crossword, before monochrome endpiece ‘Jungle World’ explores the violent existence of bugs and minibeasts.

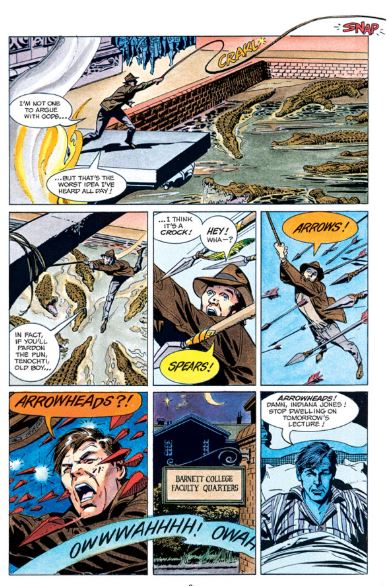

Cover-dated May 1953, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan #44 sees the Jungle Lord enjoying a quiet ride over vast hidden Pal-Ul-Don on his giant eagle Argus when he saves a tiny shepherd from a vulture as big as the mighty raptor Tarzan rides. In ‘Tarzan and the Little Spearmen’ this good deed soon sours. Coro of Saparta is grateful and desperate and happy in turn as the benevolent giant and his equally immense pal Muviro hunt down the ferocious carrion feeders who find living little people more tasty than corpses. Sadly, the interaction sparks civil war between the farming fraternity and now-unemployed spearman clan who used to defend them, especially after Tarzan teaches them the high-tech marvel of archery…

Pathos and nostalgia hit hard in second saga ‘Tarzan and the Strange Balu’ as a she-ape finds a human baby and replaces her own dead newborn with him. Poor, grieving Kalahari will not surrender the infant, leaving the Ape-Man in a double bind: finding the child’s real family and saving the mother surrogate from heartbreak…

The task is made even harder but more gratifying when Tarzan discovers vile slavers have been transporting a white woman to market…

The issue ends with a stunning pinup of Argus and a GIANT-giant vulture and contemporary house ad before ERBT #45 (June 1953) opens with ‘Tarzan and the Haunted Plantations’ wherein the Ape-Man visits old friend Chief Buto and learns his warrior comrade is plagued by devils and ghosts. A little careful investigation then reveals the fields where his people hire out as croppers are coveted by a bandit with knowledge of unexploited resources beneath that fruitful dirt, and Razan devises a sneaky scheme…

‘Boy and the Shamba Raider’ again focuses on the exploits of Korak-to-come as the kid and his pal Dombie take executive action to trap rogue water buffalo raiding crops and attacking workers. They wouldn’t have had to if the adult warriors had listened to them in the first place…

Epic fantasy follows in ‘Tarzan Returns to Cathne’ when the Jungle Man and Waziri’s Pal-Ul-Don explorations bring them into conflict with sabretooth tigers attacking the war-lions of Queen Elaine of Cathne. The staunch friend and ally is a fugitive now as her husband King Jathon is gone and usurper Timon rules. The madman is unstoppable and seeks to conquer sister city Athne, but Tarzan has other ideas and the wits to implement them…

The issues closes with another house ad and ‘Tarzan’s World’ pinup of the Dangina (Cape Hunting Dog) before we segue into final entry Tarzan #46 .

Dated July 1953 it begins with ‘Tarzan Defends a City’ as the Ape-Man and not-dead Jathon (surprise!) trek back to Cathne with super-colossal war lion Goliath, only to find the citadel under siege by crocodile-riding Terribs from the Great Swamp. Things look bleak until the Gallugos – freshly fled from the cannibal Kando-Mors – arrive and turn the muddy tide. All they want in return is land to build their new city…

Back in regular Africa, ‘Boy Faces the Fangs of the Mamba’ after Matusi witchdoctor Ungali – having failed to kill Tarzan – frames his annoying spawn Boy for theft and orchestrates a lethal trial by snake. Sadly for the villain, Ape-Man arrives just in time…

This titanic tome terminates with whimsical mystery ‘Tarzan and the Treasure of the Apes’ as brutal unscrupulous white hunters discover the great apes dubbed “mangani” are all bedecked in priceless jewels. Ruthlessly stalking the vain bedazzled beasts the safari killers even manage to wound Tarzan, before he convinces the apes to surrender their “pretty stones” in favour of something better: something edible.

The Jungle King then delivers a unique judgement that might not look like justice but truly is nothing but…

Although these are tales from a far-off, simpler time they have lost none of their passion, inclusivity and charm, whilst the artistic virtuosity of Jesse Marsh looks better than ever. Perhaps this time a few more people will “get” him…

Edgar Rice Burroughs® Tarzan®: The Jesse Marsh Years volume 9 © 1953, 2011, Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. Tarzan ® Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. All rights reserved.

In 1952 Jack of all comics trades Keith Giffen was born. We haven’t reviewed Ambush Bug, Legion of Super-Heroes or his Doom Patrol yet, so why not recall gleeful glory days with Justice League International volume 1?

In 1978 screen writer and comics luminary Robert Kirkman was born. You probably know him best for Walking Dead volume 1: Days Gone Bye.