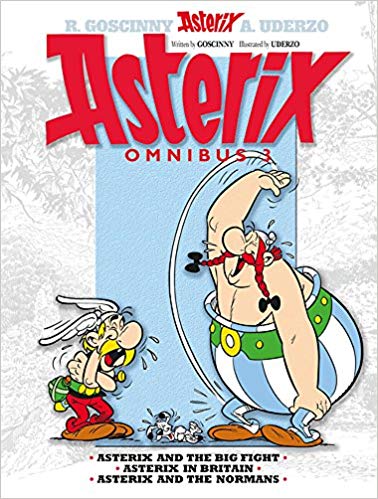

By René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Orion)

ISBN: 978-1-44400-427-4 (HB)Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 978-1-44400-475-5 (PB)

Asterix the Gaul is one of Europe’s – more specifically France’s – most exciting and rewarding contributions to global culture: a cunning little paragon of the underdog spirit who resists the iniquities, experiences the absurdities and observes the myriad wonders of Julius Caesar’s Roman Empire with brains, bravery and a magic potion bestowing incredible strength, speed and vitality. The savvy smarts are all his own…

One of the most-read comics in the world, his chronicles have been translated into more than 100 languages (including Latin and ancient Greek for educational purposes); with 14 live-action and animated movies, 55 board and video games and even into his own theme park (Parc Astérix, near Paris).

More than 370 million copies of 37 Asterix books have sold worldwide, making Goscinny & Uderzo France’s bestselling international authors.

The diminutive, doughty hero was created by two of the art-form’s greatest masters, René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo who were already masters of the form and at the peak of their creative powers. Although their perfect partnership ended in 1977 with the death of the terrifying prolific scripter Goscinny, the creative wonderment still continues – albeit at a slightly reduced rate of rapidity.

Asterix launched in 1959 in the very first issue of Pilote (with a teaser premiere page appearing a week earlier in a promotional issue #0). The feature was a massive hit from the start. Initially Uderzo continued working with Charlier on Michel Tanguy, (Les Aventures de Tanguy et Laverdure), but soon after the first epic escapade was collected as Astérix le gaulois in 1961, it became clear that the series would demand most of his time – especially as the incredible Goscinny never seemed to require rest or run out of ideas (after the writer’s death the publication rate dropped from two books per year to one volume every three to five).

By 1967 the strip occupied all Uderzo’s time and attention. In 1974 the partners formed Idéfix Studios to fully exploit their inimitable creation and when Goscinny passed away three years later Uderzo was, after much effort, convinced to continue the adventures as writer and artist, producing a further ten volumes.

Like all great literary classics, the premise works on two levels: younger readers enjoy an action-packed, lavishly illustrated comedic romp of sneaky, bullying baddies getting their just deserts whilst crustier readers enthuse over the dry, pun-filled, sly and witty satire, enhanced for English speakers by the brilliantly light and innovative touch of master translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who played no small part in making the indomitable Gaul so palatable to the Anglo-Saxon world.

The stories were set on the tip of Uderzo’s beloved Brittany coast in the year 50 BCE, where a small village of redoubtable warriors and their families resist all efforts of the Roman Empire to complete their conquest of Gaul. Unable to defeat these Horatian hold-outs, the Empire resorts to a policy of containment and the little seaside hamlet is perpetually hemmed in by the heavily fortified garrisons of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.

The Gauls don’t care: they daily defy the world’s greatest military machine by just going about their everyday affairs, protected by a magic potion provided by the resident druid and the shrewd wits of a rather diminutive dynamo and his simplistic best friend…

By the time Asterix and the Big Fight first ran in Pilote #261-302 in 1964 (originally entitled Le Combat des chefs or ‘The Battle of the Chiefs’) the feature was a fixture in millions of lives.

Here another Roman scheme to overwhelm the hirsute hold-outs begins when Totorum’s commander Centurion Nebulus Nimbus and his aide-de-camp Felonius Caucus try using an old Gaulish tradition to rid themselves of the rebels.

The Big Fight is a hand-to-hand duel between chiefs, with the winner becoming ruler of the loser’s tribe. All the Romans have to do is find a puppet, have him defeat fat, old Vitalstatistix and their perennial problem goes away for good. Luckily, just such a man is Cassius Ceramix: chief of Linoleum, a hulking brute and, most importantly, a keen lover of all things Roman…

Even such a cunning plan is doomed to failure whilst Vitalstatistix uses magic potion to increase his strength, but what if the Druid Getafix is taken out first?

When the Romans attempt to abduct the old mage, Obelix (who fell into a vat of potion as a baby and grew into a genial, permanently superhuman, eternally hungry goliath) accidentally bounces a large menhir off the druid’s bonce, causing amnesia and a touch of insanity…

Although not quite what they intended, the incapacitation of Getafix emboldens the plotters and the Gallo-Roman Ceramix’s challenge is quickly delivered and reluctantly accepted. With no magic potion, honour at stake and the entire village endangered, desperate measures are called for. Asterix and Obelix consult the unconventional sage (even for druids) Psychoanalytix – who specialises in mental disorders – and Vitalstatistix is forced to diet and begin hard physical training!

Unfortunately, when Obelix shows Psychoanalytix how Getafix sustained his injury the net result is two crazy druids, who promptly begin a bizarre bout of magical one-upmanship. As the crucial combat begins and Vitalstatistix valiantly battles his hulking, traitorous nemesis, Getafix accidentally cures himself, which is lucky as the treacherous Nebulus Nimbus and Felonius Caucus have no intention of losing and have perspicaciously brought along their much-abused Legions to crush the potion-less Gauls, should Ceramix let them down…

Manic and deviously cutting in its jibes at the psychiatric profession, this wildly slapstick romp is genuinely laugh-a-minute and one of the very best Goscinny tales.

Following the established pattern, after a “home†adventure our heroes went globe-trotting in their next exploit -although not very far…

Asterix in Britain originated in 1965 (Pilote#307-334) and followed Caesar’s conquest of our quirky country. It was never a fair fight: Britons always stopped in the afternoon for a cup of hot water and a dash of milk and never at the weekend, so those were the only times the Romans attacked…

Just so’s you know: by this time the Gallic wonders were already fairly well known on our foggy shores. The strips had been appearing in UK weekly anthology Valiant since November 1963, graduating to Ranger (1965-66) and Look & Learn (1966). Set in Britain circa 43 AD and entitled Little Fred and Big Ed, Little Fred, the Ancient Brit with Bags of Grit, Beric the Bold, Britons Never, Never, Never Shall Be Slaves! and In the Days of Good Queen Cleo. The first true Asterix album was subsequently released in 1969 by Brockhampton Press, with all names and locations just as we know them today.

After the conquest, in Cantium (Kent) one village of embattled Britons hold out against the invaders and they send Anticlimax to Gaul where his cousin Asterix has successfully resisted the Romans for absolutely ages. Always happy to oblige, the Gauls whip up a barrel of magic potion and the wily warrior and Obelix accompany Anticlimax on the return trip. Unfortunately, during a brief brouhaha with a Roman galley in the channel, the invaders discover the mission and begin a massive hunt for the rebels and their precious cargo…

As the trio make their perilous way to Cantium, the entire army of occupation is hard on their heels and it isn’t long before the barrel goes missing…

Simply stuffed with good natured jibes about British cooking, fog, the Tower of Londinium, warm beer, council estates, the still un-dug Channel tunnel, boozing, the Beatles (it was the swinging Sixties, after all), sport, fishing and our national beverage, this action-packed, wild frenetic chase yarn is possibly the funniest of all the Asterix books… if you’re British and possess our rather unique sense of humour, eh, wot…?

Asterix and the Normans debuted in Pilote #340-361 (1966) and showed how Vikings (who would eventually colonise parts of France as Northmen or “Normansâ€) first encountered our heroic Gauls and learned some valuable lessons…

The action opens with Chief Vitalstatistix reluctantly taking charge of his spoiled teenaged nephew Justforkix, intending to make a man of the flashy brat from Lutetia (Paris). The country girls go for his style and modern music (spoofing Elvis Presley in the original and the Rolling Stones in the English translation) and the lad’s glib tongue even convinces the Bard Cacofonix that his “unique†musical talent would be properly appreciated in the big city…

Meanwhile, a shipload of Vikings have fetched up on the beach, looking for the answer to a knotty question.

Rough, tough and fierce, the Scandinavians have no concept of fear, but since they have heard that the emotion can make people fly, they’re determined not to leave until they have experienced terror first hand…

They’ve met their match in the Gaulish villagers, but Justforkix is a different matter. The once-cool lad is a big ball of cowardy-custardness when confronted by the Normans, so the burly barbarians promptly snatch him, insisting he teach them all about that incomprehensible emotion…

Canny Asterix knows fighting Normans is a waste of time, but reasons the only way to get rid of them is to teach them what fear is like. If violence won’t work then what’s needed is something truly horrible… but Cacofonix and his assorted musical instruments are already on their way to fame and fortune in Lutetia. If only Obelix and Dogmatix can find him and save the day…

Daft and delicious, this superbly silly tale abounds with comedy combat and confusion; a perfect mix of gentle generational jibing and slaphappy slapstick with a twist ending to boot…

Outrageously fast-paced, funny and magnificently illustrated by a supreme artist at the very peak of his form, these historical high jinks cemented Asterix’s growing reputation as a world treasure and as these albums are available in a wealth of differing formats and editions – all readily available from a variety of retail and internet vendors or even your local charity shop – there’s no reason why should miss out on all the fun.

Asterix is sublime comics storytelling and if you’re still not au fait with these Village People you must be as Crazy as the Romans ever were…

© 1964-1965 Goscinny/Uderzo. Revised English translation © 2004 Hachette. All rights reserved.