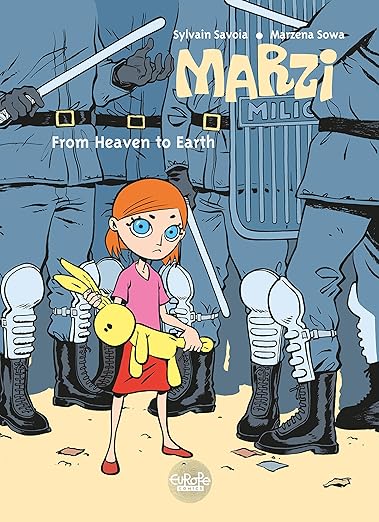

By Marzena Sowa & Sylvain Savoia, translated by Anjali Singh/Mediatoon Licensing (Europe Comics)

ISBN: 979-1-03280-391-2 (digital edition only) ASIN: ?B0C1JLQFMV

As you’re surely aware by now, our Continental cousins are exceeding adept at exploring humanity’s softer, more introspective sides through comics. Here is another autobiographical tome, detailing the life of a little Polish girl growing up in an era of massive social change: a masterclass in emotive, evocative, vibrantly funny and ruthlessly sensitive storytelling to delight our senses by quietly affirming people everywhere are basically the same…

Originally released in France in 2006 as Marzi, tome 2: Sur la terre comme au ciel, this charming episodic collation continued a sequence of seven cartoon memoires by writer Marzena Sowa and her work/life partner Sylvain Savoia. They first met when she came to Paris from Poland as an exchange student, and he – a successful cartoonist and graphic novelist – quickly realised the potential of her family anecdotes as she spoke of growing up in a subjugated Soviet satellite nation at the tumultuous tail end of the Cold War…

Their published collaborations were a hit in Europe, and first translated into English for DC/Vertigo in 2011 (still available if you prefer physical books). At that time, media hype concentrated on the political aspects, but if you can, when reading this version, try to ignore that just as the creators did. It’s a shaping element and plot point – albeit a omnipresent and potent one – like boarding at Hogwarts or growing up in the Teen Titans, but the setting is almost never what the stories are about. These are tales of childhood and finding comfort. Inspiration and happiness wherever you can, not a fabricated kid’s adventure like Emil and the Detectives or a historical testament like The Diary of Anne Frank…

Marzna Sowa was born in Stalowa Wola, Podkarpackia, Poland on April 8th 1979. She grew up mostly ordinary like all her friends and family, but after achieving maturity during some of the most eventful years of the last century, changed her life path in 2001 when she left Jagiellonian University, Krakow for Bordeaux’s Michel de Montaigne University to complete studies in Literature. The how and why will become great comics in later volumes, You’ll just have to be patient or buy all the books now.

On meeting Savoia, mutual attraction became a working partnership with the first Marzi tome Petite Carp published in 2005. The last to date was released in 2017. Her other award-winning tales include N’embrassez pas qui voulez (Don’t Kiss Who You Want – 2013, art by Sandrine Revel) and Tej nocy dzika paprotka, (with Berenika Kolomycka). After further schooling to become a videographer, Sowa moved into Cinema, writing screenplays and directing documentaries while still scripting comics like La Grande Métamorphose de Théo (2022 with Geoffrey Delinte) and La Petite Évasion (2022 with Dorothée de Monfreid).

Savoia was born in 1969 in Reims and initially studied at the Saint Luc Institute in Brussels. In 1993 he co-founded art workshop 510TTC, crafting his first comics – Reflets Perdus – from a Jean-David Morvan script before beginning their extended series Nomad. Later hits included Al’Togoat (2003), Les Esclaves oubliés de Tromelin and Henri Cartier-Bresson, Allemagne 1945, supplemented by poster making, advertising art and training manual design and illustration.

Since 2018 he has helmed educational series Le Fil de l’Histoire raconté par Ariane & Nino (On the History Trail), enjoying further success with Sowa in Les esclaves oubliés de Tromelin and Petit Pays. In 2020 Savoia was made a Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters.

Previous book Little Carp introduced 7-year-old Marzi, growing up in a Soviet-built apartment block. There are always shortages and long queues at the housing estate store, but somehow the market always has most of what people need. Dad works with Zdzich in the Huta Stalowa Wola, the city’s only factory, which has its own perks and perils…

Smart and observant but perhaps thinking too much, Marzi’s also – to her excitably loud and frequently angry mum’s consternation – a very picky eater, only barely aware of the effort dad must make to support them. Of course daughter is grateful, but also deeply concerned about so many things she can’t change…

State-controlled housing is short on amenities and variety (there are only two kinds of apartment available – small or bigger) with no play facilities, so kids cluster around the elevator on her floor (the fifth) to play their games vertically. Favourite is messing with lift buttons so the carriage stops at every floor. They also like ringing doorbells and running away. Marzi is great at the latter but hampered in the former as she’s afraid to ride the grim grey box and will always use the stairs if she can…

She has a strong bond with Andrzej, Magda, both Anias and especially feisty Monika, who always leads at everything, like that time Ania (1) and Andrzej’s mother pierced all their ears (except Andrzej and baby Magda!) and Monika’s mum gave them all their first earrings…

Here, we resume her ruminations on December 13th 1981, with ‘The state of fear’ as – aged 2½ – she recalls how appointed head of state General Wojciech Jaruzelski was on their intermittently-working television declaring “Poland is in a State of War!” There were tanks in the streets and everybody whispered and avoided telephones. It would be years before she understood, but her parents did right away and were really, really scared…

Marzi is a little older as ‘Reality TV’ details a world of shortages where everyone hides what cash money they have. When the little lass sees colour TV for the first time and begins agitating to get one, she sees more of a world where everything is rationed and controlled by the Kupon (coupon system) dictating the dissemination of goods and foodstuffs…

Although dictatorial by diktat and “Communist” by command, Poland remained devoutly Catholic throughout Russian rule and we jump to the most important event in a child’s life in ‘God loves me’. Mama is manically devout and goes into nuclear mode as her only daughter simply cannot get with the program and do what priests and teachers demand as her class prepare for their first Holy Communion. She just can’t understand all the fuss and her First Confession is a disaster, but this day and life-change is just inescapable…

Marzi is luckier than most of her friends as Dad has an official garden (in Britain we’d call it an allotment) and her Aunt Niusia lives on an actual farm. The family always have access to extra – fresh – food and can even make extra, under-the-table cash selling produce on the openly-ignored food black market. However, the day-dreaming child’s visits to either are always fraught with unacknowledged but pragmatic brutality. Marzi has met cows, pigs, turkeys, chickens, cats, dogs and other creatures and fully understands why mum says you shouldn’t give animals names, but it can’t stop her trying to form bonds or leave food on her plates…

A weekend at Niusia’s and a new white dress for Mass on Sunday inevitably draws calamity and catastrophe when Marzi gets on the wrong side of cart horse Baska, but her “punishment” in ‘What’s bred in the bone comes out in the flesh’ is a real gift from God, after which ‘Bad grass’ sees the family stocking up on fruit & veg from the urban spread for a quick money bonanza. Sadly, after being forbidden a go on the scythe, Marzi gets caught up in observing ants at work and lets down her folks yet again…

When (relatively) rich girl Justyna joins the class, all her American bought clothes and cosmetics prove that ‘Money does smell (good)’ whereas Marzi’s new – incontinent – guinea pig ‘Perelka’ just does not, and comes to an inevitable end in the family flat. Marzi really wanted a dog anyway…

Hinting at exotic things to come, an impromptu but welcome trip to the farm in Skowierzyn results from a distant aunt (born and raised in France!) wanting to reconnect with her roots. However, the glamour promised by ‘Oh la la Elen!’ isn’t what the little dreamer was expecting, although that disappointment was then eradicated by a 15-day stay in fabulous metropolis Krakow with grandmother Jdzia, Aunt Dzidzia and Uncle Metek…

Her first extended taste of freedom supercharges Marzi’s imagination as modernity, history, fantasy and romance collide, especially after hearing the legend and seeing the statue of the dragon ‘Smok Wawelski’. Our tiny tourist is far less enamoured of patent herbal medicines like Amol, ruthlessly dispensed when she’s deemed to have overdone things…

Despite all her gripes and doubts about everything – even God is on her “unproven” list – the life of Marzi and her pals is pretty good and generally happy, but that suddenly changes in chilling final episode ‘Breathing can be hazardous to your health’. Here, Marzi is on the farm and revelling in the mucky joys of the countryside when suddenly the adults all start acting crazy. Now, no kid can go outside, eat vegetables (no loss there!) or drink milk. The trip ends suddenly and Dad drives them back to the flat in hurry. Soon every kid is having to take nasty medicine from the hospital and all outside activities are stopped. It’s spring 1986 and slowly reports are emerging that there has been an accident in a place called Chernobyl…

A skilfully shaped, enticingly enthralling paean to growing up in interesting times (and aren’t they all?), From Heaven to Earth is a celebration of independent thought: blending pranks and misunderstanding, new fun with familial strangers and with doing tedious stuff adults tell you to. Making fun where you can as your awareness deepens and a mature world is built by ever-expanding experience, and how we all grow up to be our parent in unbalanced doses of imitation and utter rejection…

Marzi is definitely about independence and freedom, but it’s personal not national and inherently hopeful: the tale of a fish out of water learning to swim her own way. If you want polemical condemnation and confirmation of your own prejudices, look elsewhere. Better yet, stick around to see how a delightful and unique individual lived her own best life…

© 2017 – DUPUIS – SOWA & SAVOIA. All rights reserved.