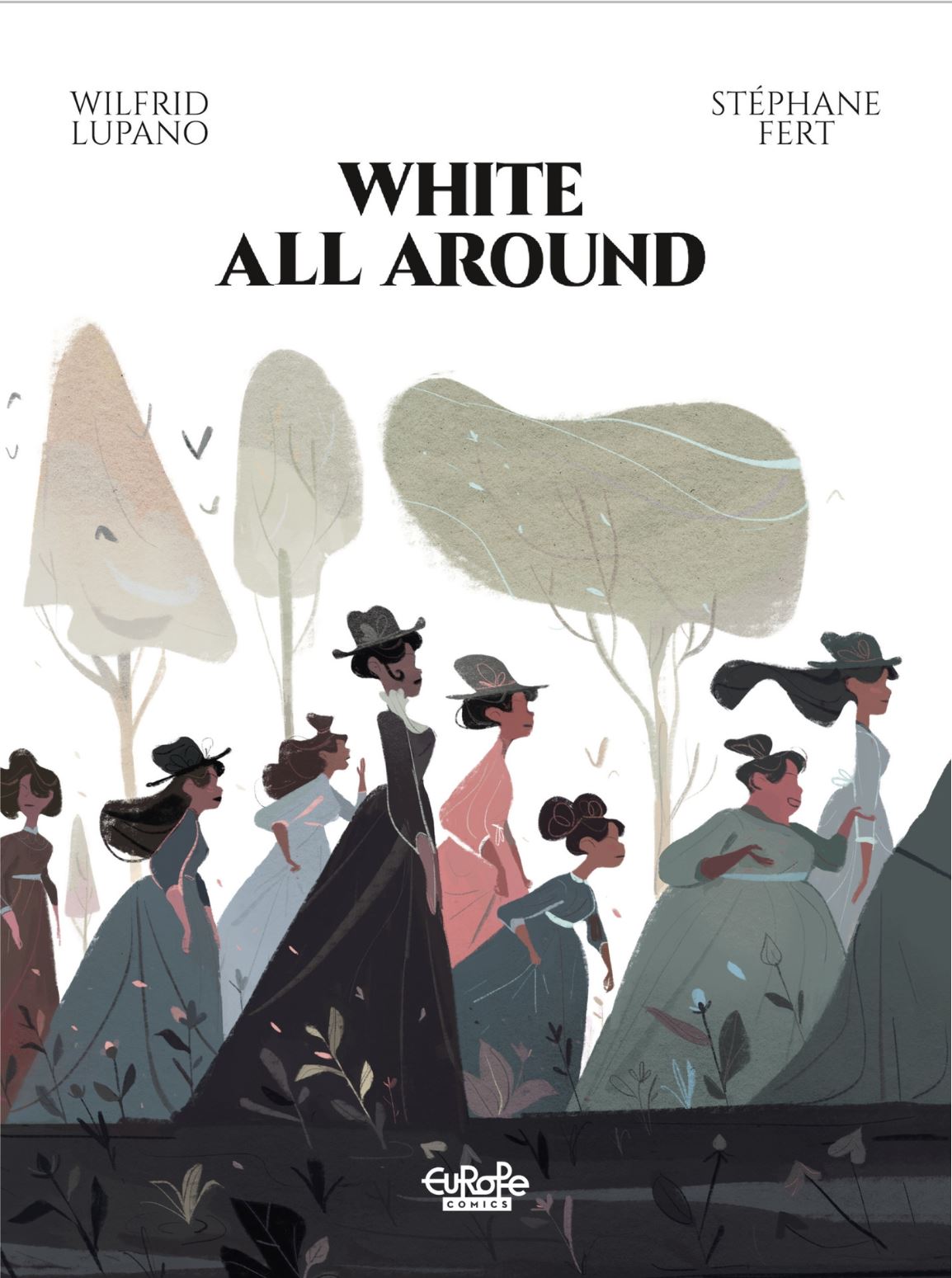

By Wilfrid Lupano & Stéphane Fert, translated by Montana Kane (Europe Comics)

No ISBN: digital only edition

When we actually get to hear it, history is an endlessly fascinating procession of progress and decline that plays out eternally at the behest of whoever’s in power at any one time. However, don’t be fooled. It’s never about “opinions” or “alternative facts”: most moments of our communal existence generally happened one way with only the reasons, motivations and repercussions shaded to accommodate a preferred point of view.

The best way to obfuscate the past is to tell everyone it never happened and pray nobody goes poking around. So much you never suspected has been brushed under a carpet and erased by intervening generations proceeding without any inkling…

Entire sections of society have been unwritten in this manner but always there have been pesky troublemakers who prod and probe, looking for what’s been earmarked for forgetting and shine a light on the history that isn’t there.

One such team of investigators are Wilfrid Lupano & Stéphane Fert who in 2020 released a sequential graphic narrative account of a remarkable moment of opportunity that was quashed by entrenched bigotry, selfish privilege and despicable intolerance…

The translated Blanc autour is available to English-reading audiences only in a digital format thus far and opens with a context-filled Foreword before we meet servant girl Sarah Harris as she is tormented by ruffian child Feral, reading to her from an infamous new book…

Set one year after Nat Turner’s doomed black uprising of August 21st 1831 (in Southampton County, Virginia), this true tale took place in a land still reeling and terrified.

New preventative measures to control and suppress the slave population included banning black gatherings of three or more people, an increase in public punishments like floggings, lynchings and ferocious policing if not outright outlawing of negro literacy. The posthumous publishing of Thomas R. Gray’s The Confessions of Nat Turner had created a best seller that further outraged and alarmed Americans…

Even in 1832, and hundreds of miles north in genteel Canterbury, Connecticut black people were careful to mind their place. It might be a “Free State”, where slavery was illegal but even here Negros were an impoverished underclass…

Sarah, however, is afflicted with a quick, agile and relentlessly questioning mind. She craves knowledge and understanding the way her fellow servants do food, rest and no trouble. One day, fascinated by the way water behaves, she plucks up her courage and asks the local school teacher to explain.

Prudence Crandall is a well-respected and dedicated educator diligently shepherding the young daughters of the (white) citizenry to whatever knowledge they’ll need to be good wives and mothers, but when the brilliant little servant girl quizzes her, the teacher is seized by an incredible notion…

When a new term starts Sarah is the latest pupil, and despite outraged and increasingly less polite objections from the civic great and good – all proudly pro negro advancement, but not necessarily here or now – Miss Crandall is adamant that she should remain. When parents threaten to remove their children, she goes on the offensive, declaring the school open for the “reception of young ladies and little misses of color”…

Her planned curriculum includes reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, natural and moral philosophy, history, drawing and painting, music on the piano, and the French language, and by sending it along with her intentions to Boston Abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, Crandall declare war on intolerance and ignorance in her home town. Sadly, her proud determination unleashes an unstoppable wave of sabotage, intimidation, sly exclusion, social ostracism and naked hatred against herself and her negro student…

She even tried to defend the move at the Municipal Assembly, only to learn that only men were allowed to speak there…

Crandall’s response is to make her Canterbury Female Boarding School exclusively a place for a swiftly growing class of black girls. All too soon, politicians and lawmakers got involved and harassment intensified to the point of terrorism and murder. Connecticut even legislated that it was illegal to educate coloured people from out of State…

The school became another piece in the complex political game between abolitionists and slave-owing states but still managed to enhance the lives and intellects of its boarders, until 1834 when Prudence Crandall stood trial for the crime of teaching black children. When she was exonerated, the good people of Canterbury took off the kid gloves…

Although this war was never going to be won, Crandall’s incredible stand for tolerance, inclusivity and universal education was a minor miracle of enlightenment, attracting students from across America and countering the long-cherished “fact” that blacks and females had no need or even capacity for learning. Moreover, though the bigots managed to drive her out, she and her extraordinary pupils retrenched to continue the good work in another state: one more willing to risk the status quo…

This amazing story is delivered as a fictionalised drama made in a manner reminiscent of a charming and stylish Disney animated feature, but the surface sweetness and breezy visuals are canny subterfuge. Scripter Wilfred Lupano (Azimut; Little Big Joe; Valerian & Laureline: Shingouzlooz Inc.; The Old Geezers; Vikings dans la brume) and illustrator Stéphane Fert (Morgane; Axolot; Peau de Mille Bêtes) deploy a subtle sheen of beguiling fairy tale affability to camouflage their exposure of a moving, cruel and enraging sidebar to accepted history: one long overdue for modern reassessment.

The creators also wisely leaven the load with delightful, heart-warmingly candid moments exploring the feelings and connections of the students, and balance tragedy with moments of true whimsy and life-affirming fantasy: but please beware – it does not end well for all…

The book also includes an Afterword by Joanie DiMartino – Curator of the Prudence Crandall Museum – tracing in biographical snippets, the eventful lives, careers and achievements of eleven of the boldly aspirational scholars of the Crandall School’s first class.

White All Around is a disturbing yet uplifting story that every concerned citizen should read and remember. After all, learning is a privilege, not a right… unless we all defend and advance it…

© 2021 DARGAUD BENELUX, (Dargaud-Lombard s. a.) – LUPANO & FERT. All rights reserved. English translation © 2009 Cinebook Ltd.