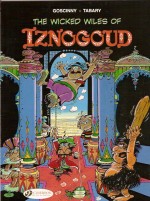

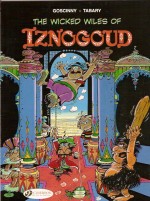

By René Goscinny & Jean Tabary, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-905460-46-5

René Goscinny was one of the most prolific, and therefore remains one of the most read, writers of comic strips the world has ever seen. Born in Paris in 1926, he was raised in Argentina where his father taught mathematics. From an early age he showed artistic promise, and studied fine arts, graduating in 1942.

While working as junior illustrator in an ad agency in 1945 an uncle invited him to stay in America, where he found work as a translator. After his National Service in France he settled in Brooklyn and pursued an artistic career becoming in 1948 an assistant for a little studio that included Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Jack Davis and John Severin as well as European giants-in-waiting Maurice de Bévère (“Morris”, with whom he produced Lucky Luke from 1955-1977) and Joseph Gillain (Jijé). He also met Georges Troisfontaines, head of the World Press Agency, the company that provided comics for the French magazine Spirou.

After contributing scripts to Belles Histoires de l’Oncle Paul and ‘Jerry Spring’ Goscinny was made head of World Press’Paris office where he met his life-long creative partner Albert Uderzo (Jehan Sepoulet, Luc Junior) as well as creating Sylvie and Alain et Christine (with “Martial”- Martial Durand) and Fanfan et Polo (drawn by Dino Attanasio).

In 1955 Goscinny, Uderzo, Charlier and Jean Hébrard formed the independent Édipress/Édifrance syndicate, creating magazines for general industry (Clairon for the factory union and Pistolin for a chocolate factory). With Uderzo he produced Bill Blanchart, Pistolet and Benjamin et Benjamine, and himself wrote and illustrated Le Capitaine Bibobu.

Goscinny seems to have invented the 9-day week. Using the pen-name Agostini he wrote Le Petit Nicholas (drawn by Jean-Jacques Sempé), and in 1956 he began an association with the revolutionary magazine Tintin, writing stories for many illustrators including Signor Spagetti (Dino Attanasio), Monsieur Tric (Bob De Moor), Prudence Petitpas (Maréchal), Globule le Martien and Alphonse (both by Tibet), Modeste et Pompon (for André Franquin), Strapontin (Berck) as well as Oumpah-Pah with Uderzo. He also wrote strips for the magazines Paris-Flirt and Vaillant.

In 1959 Édipress/Édifrance launched Pilote, and Goscinny went into overdrive. The first issue starred his and Uderzo’s instant masterpiece Asterix the Gaul, and he also re-launched Le Petit Nicolas, Jehan Pistolet/Jehan Soupolet and began Jacquot le Mousse and Tromblon et Bottaclou (drawn by Godard). When Georges Dargaud bought Pilote in 1960, Goscinny became editor-in-Chief, but still found time to add new series Les Divagations de Monsieur Sait-Tout (Martial), La Potachologie Illustrée (Cabu), Les Dingodossiers (Gotlib) and La Forêt de Chênebeau (Mic Delinx).

He also wrote frequently for television. In his spare time he created a little strip entitled Les Aventures du Calife Haroun el Poussah for Record (first episode January 15th 1962) illustrated by a Swedish-born artist named Jean Tabary. A minor success, it was re-tooled as Iznogoud when it transferred to Pilote.

Goscinny died – probably of well-deserved pride and severe exhaustion – aged 933, in November 1977.

Jean Tabary was born in Stockholm, and began his comics career in 1956 on Vaillant, illustrating Richard et Charlie, before graduating to the hugely popular boy’s adventure strip Totoche in 1959. The engaging head of a kid gang, Totoche spawned a spin-off, Corinne et Jeannot, and as Vaillant transformed into Pif, the lad even got his own short-lived comic; Totoche Posche. Tabary drew the series until 1976, and has revived it in recent years under his own publishing imprint Séguinière /Editions Tabary.

In 1962 he teamed with René Goscinny to produce imbecilic Arabian potentate Haroun el-Poussah but it was the villainous foil, power-hungry vizier Iznogoud that stole the show – possibly the little rat’s only successful plot.

With the emphasis shifted to the shifty shrimp the revamped series moved to Pilote in 1968, becoming a huge favourite, spawning 27 albums to date, a long-running TV cartoon show and even a live action movie in 2005. Following their success Goscinny and Tabary created Valentin, and Tabary also wrote Buck Gallo for Mic Delinx to draw. When Goscinny died in 1977 Tabary took over writing Iznogoud as well, moving to book length complete tales, rather than the compilations of short stories that typified their collaboration.

So what’s it all about?

Like all the best comics it works on two levels: as a comedic romp of sneaky baddies coming a cropper for younger readers, and as a pun-filled, sly and witty satire for older, wiser heads, much like its more famous cousin Asterix – and translated here with the brilliantly light touch of master translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who made the indomitable little Gaul so very palatable to the English tongue.

Iznogoud is Grand Vizier to Haroun Al Plassid, Caliph of Ancient Baghdad, but the sneaky little tyke has loftier ambitions, or as he is always shouting it “I want to be Caliph instead of the Caliph!”

The vile vizier is “aided” – and that’s me being uncharacteristically kind – in his schemes by his bumbling assistant Wa’at Alahf, and in this first album they begin their campaign with ‘Kissmet’, wherein pandemonium ensues after a talking frog is revealed to be an ensorcelled Prince who can only regain human form if kissed by a human. Iznogoud sees an opportunity if he can only trick the simple-minded Caliph into puckering up; unfortunately he forgets that he’s not the only ambitious man in Baghdad…

‘Mesmer-Eyezed’ finds him employing a surly stage hypnotist to remove the Caliph whilst ‘The Occidental Philtre’ sees him employ a flying potion obtained from a lost, jet-lagged western sorcerer, each with hilarious but painfully counter-productive results.

Tabary drew himself into ‘The Time Machine’ as a comic artist desperate to meet his deadlines who falls foul of a mystical time cabinet, but when he meets the vizier, that diminutive dastard can clearly see its Caliph-removing potential – to his eternal regret… In ‘The Picnic’ Iznogoud takes drastic action, luring Haroun Al Plassid into the desert, but as usual his best-laid plans aren’t, and the book concludes with ‘Chop and Change’ as the villain gets hold of a magic goblet which can switch the minds of any who drink from it, forgetting that Caliphs are important people who employ food-tasters…

Snappy, fast-paced slapstick and painfully delightful word-play abound in these mirthfully infectious tales and the series has become a household name in France; said the name has even entered French Political life as a term for a certain type of politician: over-ambitious, unscrupulous – and usually short.

Eight albums were translated in the 1970s and 1980s, but made little impact here: hopefully this new incarnation of gloriously readable and wonderfully affordable comedy epics will finally find an appreciative audience among British kids of all ages. I’m certainly going to be one of them…

© 1967 Dargaud Editeur Paris by Goscinny & Tabary. All Rights Reserved.