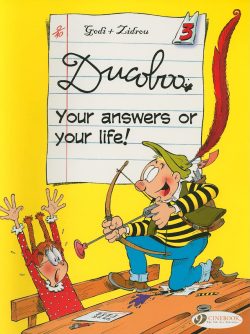

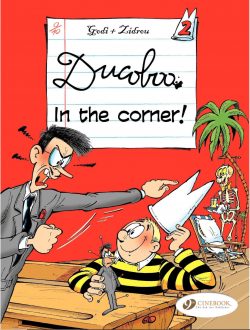

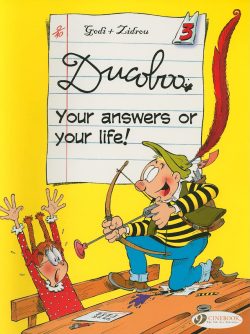

By Godi & Zidrou, coloured by Véronique Grobet & translated by Luke Spear (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-1-905460-28-1 (Album PB/Digital edition)

Back to school countdown begins now!

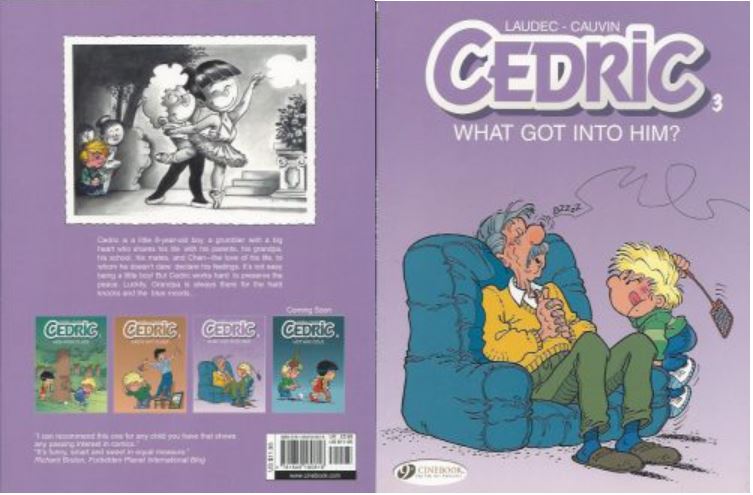

School stories and strips of every tone about juvenile fools, devils and rebels are a lynchpin of modern western entertainment and an even larger staple of Japanese comics – where the scenario has spawned its own wild and vibrant subgenres. However, would Dennis the Menace (ours and theirs), Komi Can’t Communicate, Winker Watson, Don’t Toy with Me, Miss Nagatoro, Power Pack, Cédric or any of the rest be improved or just different if they were created by former teachers rather than ex-kids or current parents?

It’s no surprise the form is evergreen: schooling (and tragically, sometimes, a lack of it) takes up a huge amount of children’s attention no matter how impoverished or privileged they are, and their fictions will naturally address their issues and interests. It’s fascinating to see just how much school stories revolve around humour, but always with huge helpings of drama, terror, romance and an occasional dash of action…

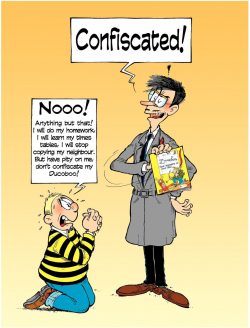

One of the most popular European strips employing those eternal but basic themes and methodology began in the last fraction of the 20th century, courtesy of scripter Zidrou (Benoît Drousie) and illustrator Godi. Drousie is Belgian, born in 1962 and for six years a school teacher prior to changing careers in 1990 to write comics like those he probably used to confiscate in class.

Other mainstream successes in a range of genres include Petit Dagobert, Scott Zombi, La Ribambelle, Le Montreur d’histoires, African Trilogy, Shi, Léonardo, a superb revival of Ric Hochet and many more. However, his most celebrated and beloved stories are the Les Beaux Étés sequence (digitally available in English as Glorious Summers) and 2010’s sublime Lydie, both illustrated by Spanish artist Jordi Lafebre. Zidrou began his comics career with what he knew best: stories about and for kids, including Crannibales, Tamara, Margot et Oscar Pluche and, most significantly, a feature about a (and please forgive the charged term) school dunce: L’Elève Ducobu…

Godi is a Belgian National Treasure, born Bernard Godisiabois in Etterbeek in December 1951. After studying Plastic Arts at the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels he became an assistant to comics legend Eddy Paape in 1970, working on the strip Tommy Banco for Le Journal de Tintin whilst freelancing as an illustrator for numerous comics and magazines. He became a Tintin regular three years later, primarily limning C. Blareau’s Comte Lombardi, but also working on gag strip Red Rétro by Vicq, with whom he also produced Cap’tain Anblus McManus and Le Triangle des Bermudes for Le Journal de Spirou in the early 1980s. He also soloed on Diogène Terrier (1981-1983) for Casterman.

Godi moved into advertising cartoons and television, cocreating with Nic Broca the animated TV series Ovide. He only returned to comics in 1991, collaborating with newcomer Zidrou on L’Elève Ducobu for Tremplin magazine. The strip launched in September 1992 before transferring to Le Journal de Mickey, and collected albums began in 1997 – 25 so far in French, Dutch, Turkish and for Indonesian readers.

When not immortalising modern school days for future generations, Godi diversified, co-creating (1995 with Zidrou) comedy feature Suivez le Guide and game page Démon du Jeu with scripter Janssens. The series spawned a live action movie franchise and a dozen pocket books plus all the usual attendant merchandise paraphernalia. English-speakers’ introduction to the series (5 volumes only thus far) came courtesy of Cinebook with 2006’s initial release King of the Dunces – in actuality the 5th European collection L’élève Ducobu – Le roi des cancres.

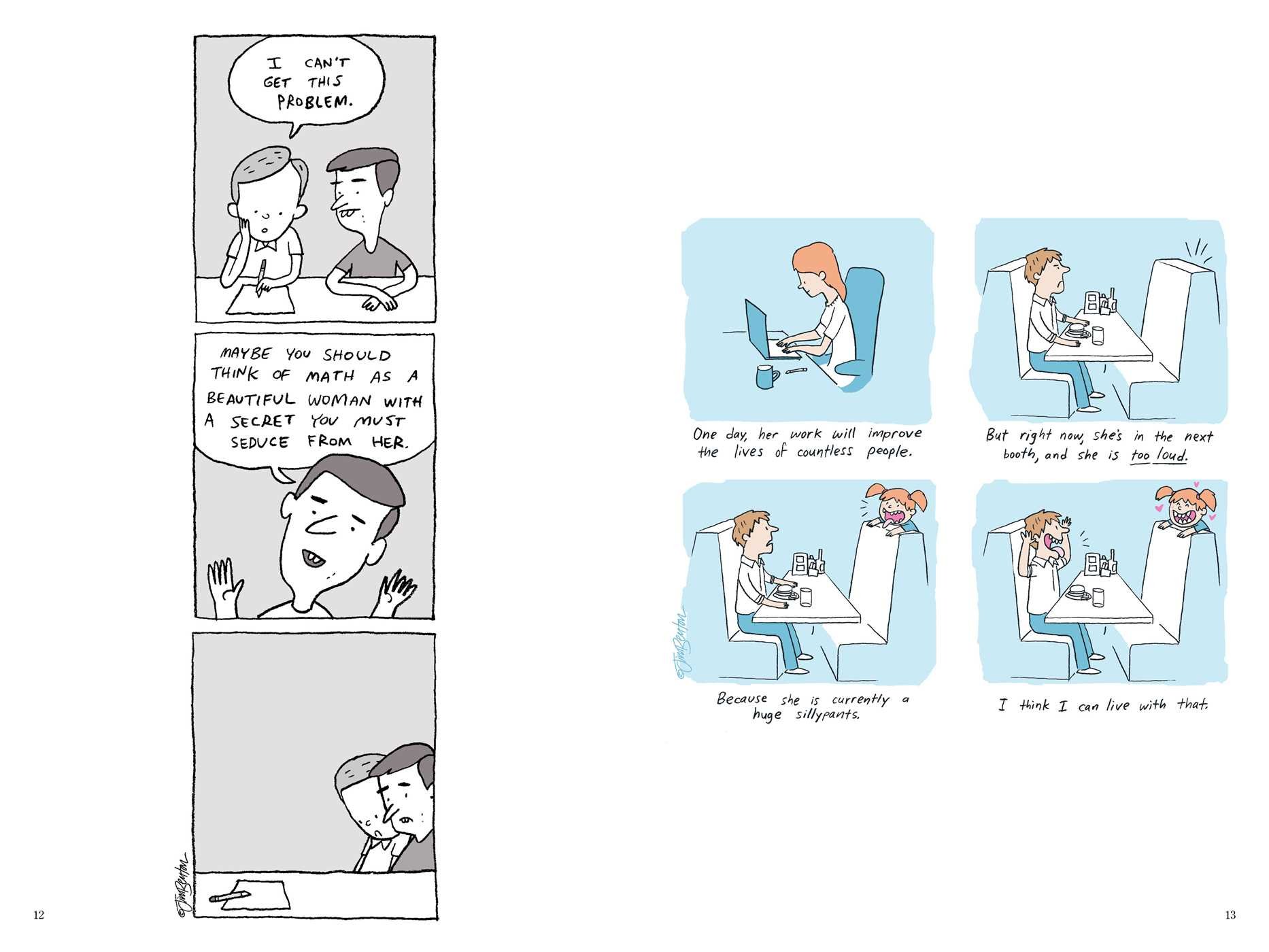

The unbeatable format comprises short – most often single page – gag strips like you’d see in The Beano, involving a revolving cast -well established albeit also fairly one-dimensional and easy to get a handle on.

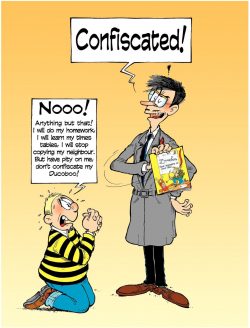

Our star is a well-meaning, good natured but terminally lazy young oaf who doesn’t get on with school. He’s sharp, inventive, imaginative, inquisitive, personable and not academical at all. We might today put him on a spectrum or diagnose a disorder like ADHD, but at heart he’s just not interested and can always find better – or at least more interesting – things to do…

Dad is a civil servant and Mum left home when Ducoboo was an infant, but then there’s a lot of that about. Leonie Gratin – the girly brainbox from whom he constantly copies answers to interminable written tests – only has a mum.

Ducoboo and his class colleagues attend Saint Potache School and are mostly taught and tested by ferocious, impatient, mushroom-mad Mr Latouche. He’s something of humourless martinet, and thanks to him, Ducoboo has spent so much time in the corner with a dunce cap on his head that he’s struck up a friendship with the biology skeleton. He (She? They!) answer to Skelly – always ready with a theory or suggestion for fun and frolics…

Released in 1999, Les Réponse ou la vie? was the third collected album: a compendium of classic clowning about that begins with another new term and Ducoboo doing his utmost to not be there.

Tracing a year in the life of all concerned, the skiver’s early antics to get illicit answers include feigning blindness, sleight of hand, outright rebellion, time-bending and stealing the keys to the small safe Leonie keeps her completed exam papers in. The champion cheat even hires private detectives and surveillance teams and tries playing poker with a fixed deck but again underestimates his swotty nemesis…

The brief blessed interlude of Christmas offers little respite before a new term brings an extended crisis. When the classroom is scheduled to get a new sink, the prime position can only be the corner almost permanently occupied by the dunce and Skelly. Appalled to be losing his second home, the boy begins a campaign of resistance. The plumber doesn’t mind: as he keeps reminding everyone, he’s paid by the hour…

With Leonie gleefully reporting ‘News from the Frontline’ the war grinds on for weeks with neither side gaining ground until a diplomatic breakthrough allows the sink to be installed. However, the plumber is still paid by the hour and has inspired Ducoboo with his proficient mien, lack of urgency and dearth of credentials. The boy now has a new dream for his future…

With labours glacially proceeding all term long, some measure of abnormality eventually returns to class, but the workman’s appeal has spread to the normal kids by the time the job is finally done. Moreover, by the time the exorbitant bill arrives, Ducoboo has engineered one last extravagant flourish…

As he and Leonie resume their eternal dance of deception, the regular, always relevant riffs episodically return: museum visits, failed bluffs (focussed on geography lessons), and other imaginative distractions allowing Ducoboo to copy answers, but they are mere preamble to the dawn of a new era as the kids discover simultaneously, the wonders and infinite temptations and potential of laptop computers…

The escalation proves so ferocious and terrible that Leonie even attempts the unthinkable: teaching Ducoboo herself…

Somehow, everyone lives to the end of another year and vacation time beckons, but even here poor Latouche cannot escape the effects of his most difficult pupil…

Wry, witty and whimsical whilst deftly recycling constant and adored childhood themes, Ducuboo is an up-tempo, upbeat addition to the genre every parent or pupil can appreciate and enjoy. If your kids aren’t back from school quite yet, why not anticipate keeping them occupied when that happens with Your answers or your life! and consider that there are kids far more demanding than even yours…

© Les Editions du Lombard (Dargaud- Lombard) 1999 by Godi & Zidrou. English translation © 2008 Cinebook Ltd.