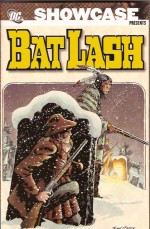

By Sergio Aragonés, Denny O’Neil, Nick Cardy & various (DC Comics)

ISBN: 978-1-4012-2295-6

By 1968 the glory-days of comic-books as a cheap mass-market entertainment were over. Spiralling costs, “free” alternatives like television and an increasing inability to connect with the mainstream markets were leaving the industry at the mercy of dedicated fan-groups with specialised, even limited, interests and worse yet, dependent on genre-trends to bolster sales.

Editorial Director Carmine Infantino, a thirty-year veteran, looked for ways to bolster DC business (already suffering a concerted attack by the seemingly unstoppable rise of Marvel Comics) and clearly remembered the old publisher’s maxim “do something old, and make it look new”. Although traditional cowboy yarns (which had ruled both TV and cinema screens since the 1950s) were also in decline, novel alternatives such as Wild, Wild West and Italian “Spaghetti Westerns” were popular, and would be a lot easier to transform into comics material than the burgeoning Supernatural craze that would come to dominate the next half-decade – but only after the repressive and self-inflicted Comics Code was re-written.

Thus Spanish/Mexican cartoonist and actor Sergio Aragonés was asked by Infantino and Editor Joe Orlando to add some unique contemporary twists to a cowboy hero they had concocted with the aid of the legendary Sheldon Mayer. Although many hands had stirred the plot, Aragonés, with dialogue provider Denny O’Neil, rendered the world-weary lonely saddle-tramp archetype into a completely fresh and original character – at least in comic-book terms – by making him a seemingly amoral wanderer with an aesthete’s sensibilities, a pacifist’s good intentions, and the hair-trigger capabilities of a top gun-for-hire. …And they played him for sardonic, tongue-in-cheek laughs.

Roguish, sexually promiscuous and always getting into trouble because his heart was bigger than his charlatan’s façade; Bat Lash caroused, cavorted and killed his way across the West – and Mexico – in one Showcase try-out (#76, August 1968) and seven bi-monthly issues (October/November 1968 – October/November 1969) before poor sales and a changing marketplace finally brought him low. Now this slim black and white tome (only 240 pages) collects those ahead-of-their-times adventures and also includes later revivals from DC Special Series #16 and a short run from the back of rival and fellow controversial cowboy Jonah Hex.

None of the Bat Lash stories had a title – which makes reviewing them a mite harder – but their strength was always that they took traditional plots and added a sardonic spin and breakneck pace to keep them fairly rattling along. It also didn’t hurt that the majority of the art was produced by that unsung genius Nick Cardy, whose light touch and unparalleled ability to draw beautiful women kept young male readers (those who bothered to try the comic) glued to the pages.

The drama begins with the Showcase introduction in which the flower-loving nomad wanders into the town of Welcome in search of a fancy feed only to find a gang of thugs and a mystery poisoner in the process of driving out the entire populace. Bat Lash #1 carried on the episodic hi-jinks as the laconic Lothario narrowly escaped a lynching only to stumble into the murder of a monk carrying part of a treasure map. Was it his finer instincts seeking retribution for the holy man, the monk’s stunning niece or the glittering temptation of Spanish gold that prompted the rootin’ tootin’ action that followed?

Issue #2 began with a shotgun wedding, ensued as the drifter became unwilling guardian to a little girl orphaned by gun-runners and brilliantly climaxed with unexpected poignancy – and calamitous gunplay…

A radical departure – even for this series – occurred in #3 when the easy Epicurean – whilst trying out the temporary role of Deputy Sheriff – encountered a hanging judge who thought he was a Roman Emperor, before Lash crossed the border into revolutionary Mexico in issue #4 to become embroiled in an assassination plot; a tale as much gritty as witty which displayed the emotional depths of the rambling man.

Still in Mexico for #5 the creative team pitted the dashing rogue against his near-equal in raffish charm and gunplay when he met the deadly bandito Sergio Aragones. Of course they were both outmatched by the delightfully deadly Senorita Maribel…

Mike Sekowsky pencilled most of issue #6 for Cardy to ink: a dark, tragic origin tale which revealed the anger and tears behind the laughter, whilst Bat Lash #7 set the far-from-heroic wanderer on the trail of a younger brother he had believed dead for ten years…

And that’s where it was left for nearly a decade. In 1978 the giant sized anthology comic DC Special Series (#16) produced a Western-themed issue for which O’Neil and artist George Moliterni crafted a slick, sly murder-mystery set in San Francisco where an older Bat Lash was a professional gambler enveloped in a deadly war between Irish gangs and Chinese immigrant workers. This compelling, enjoyable yarn eventually led to a four-issue run as back-up in Jonah Hex #49-52 (June-September 1981) wherein the charming chancer won a New Orleans bordello in a river-boat card game and despite numerous attempts to kill him took possession of the Bourbon Street Social Club.

Was he that hungry for lazy luxury and female companionship, or was it perhaps that he knew a million dollars in Confederate gold was hidden there in the dying days of the Civil War – and never found?

Scripter Len Wein and the incomparable Dan Spiegle concluded this criminally under-appreciated character’s solo exploits in fine style; which only leaves it to you to buy this brash and bedazzling book to convince DC’s powers-that-be to give the foppishly reluctant gunslinger another crack at the big time – and no, I’m not forgetting the recent, ill-conceived make-over miniseries…

Enchanting, exciting, wry and wonderful, this is a book for all readers of fun fiction and a superb example of comics’ outreach potential.

© 1968, 1969, 1978, 2006 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved.