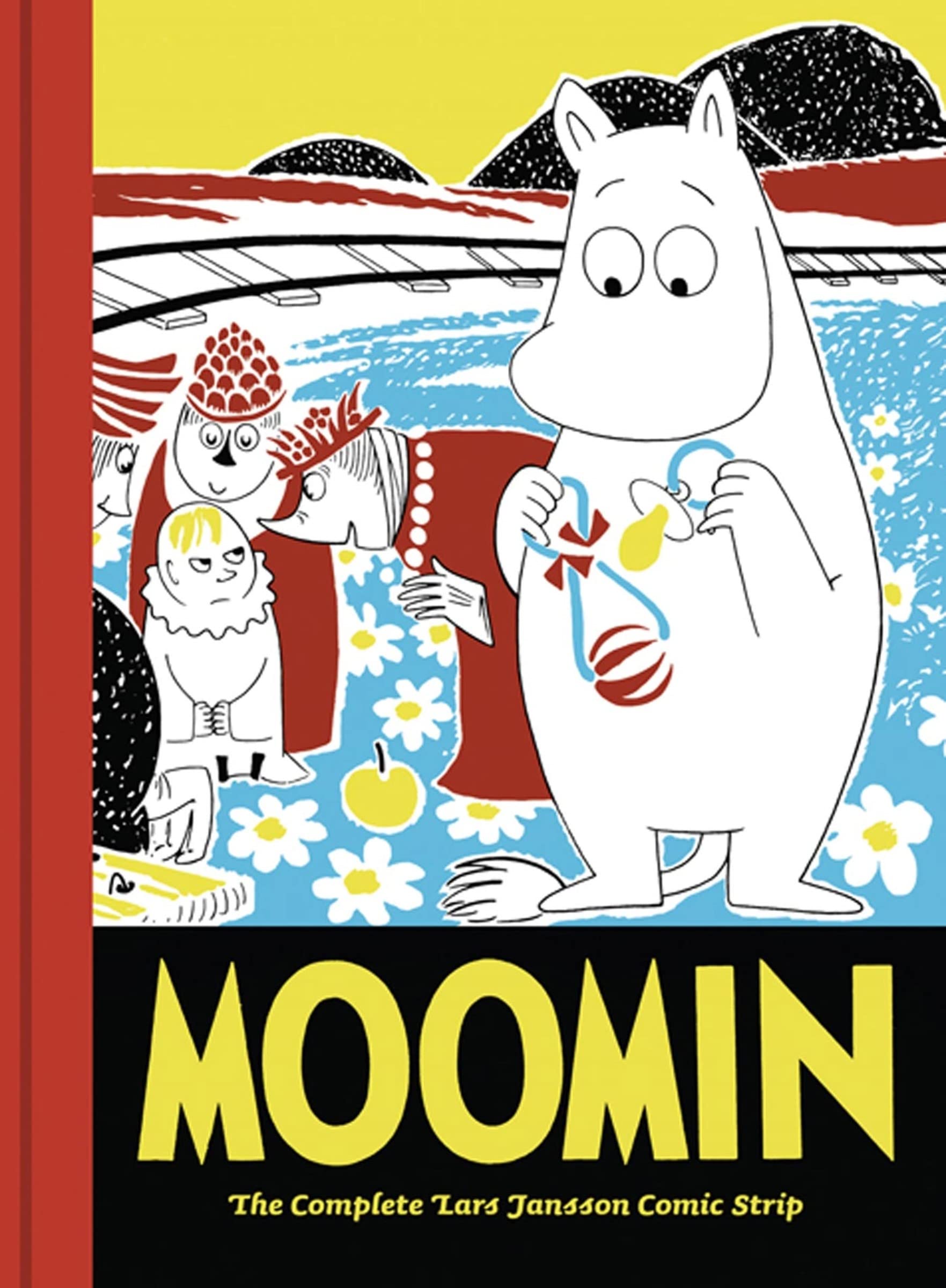

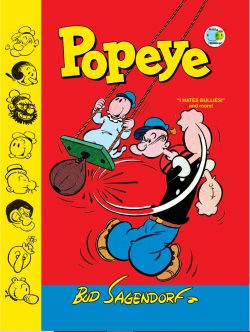

By Elzie Crisler Segar with Kevin Huizenga & various (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1- 68396-668-5 (TPB/digital edition)

Popeye embarked in the Thimble Theatre comic feature with the instalment for January 17th 1929. The strip was an unassuming vehicle that had launched on 19th December 1919: one of many newspaper cartoon funnies to parody, burlesque and mimic the era’s silent movie serials. Its more successful forebears included C.W. Kahles’ Hairbreadth Harry or Ed Wheelan’s Midget Movies/Minute Movies – which Thimble Theatre replaced in media mogul William Randolph Hearsts’ papers.

All the above-cited strips employed a repertory company of characters playing out generic adventures based on those expressive cinema antics. Thimble Theatre’s cast included Nana and Cole Oyl, their gawky, excessively excitable daughter Olive, diminutive-but-pushy son Castor and Olive’s sappy, would-be beau Horace Hamgravy.

The series ticked along nicely for a decade: competent, unassuming and always entertaining, with Castor and Ham Gravy (as he became) tumbling through get-rich-quick schemes, frenzied, fear-free adventures and gag situations until September 10th 1928, when explorer uncle Lubry Kent Oyl gave Castor a spoil from his latest exploration of Africa.

It was the most fabulous of all birds – a hand-reared Whiffle Hen – and was the start of something truly groundbreaking…

Whiffle Hens are troublesome, incredibly rare and possessed of fantastic powers, but after months of inspired hokum and slapstick shenanigans, Castor was inclined to keep Bernice – for that was the hen’s name – as a series of increasingly peculiar circumstances brought him into contention with ruthless Mr. Fadewell, world’s greatest gambler and king of the gaming resort dubbed ‘Dice Island’.

Bernice clearly affected and inspired writer/artist E.C. Segar, because his strip increasingly became a playground of frantic, compelling action and comedy during this period…

When Castor and Ham discovered that everybody wanted the Whiffle Hen because she could bestow infallible good luck, they sailed for Dice Island to win every penny from its lavish casinos. Big sister Olive wanted to come along, but the boys planned to leave her behind once their vessel was ready to sail. It was 16th January 1929…

The next day, in the 108th episode of the saga, a bluff, brusquely irascible, ignorant, itinerant and exceeding ugly one-eyed old sailor was hired by the pathetic pair to man the boat they had rented, and the world was introduced to one of the most iconic and memorable characters ever conceived.

By sheer surly willpower, Popeye won readers hearts and minds: his no-nonsense, grumbling simplicity and dubious appeal enchanting the public until, by the end of the tale, the walk-on had taken up full residency. He would eventually make Thimble Theatre his own…

The Sailor Man affably steamed onto the full-colour Sunday Pages forming the meat of this curated collection covering March 6th 1932-November 26th 1933. This paperback prize is the second of four that will contain Segar’s entire Sunday canon: designed for swanky slipcases. Spiffy as that sounds, the wondrous stories are also available in digital editions if you want to think of ecology or mitigate the age and frailty of your spinach-deprived “muskles”…

Elzie Crisler Segar was born in Chester, Illinois on 8th December 1894, son of a handyman. Elzie’s early life was filled with the solid, earnest blue-collar jobs that typified his generation of cartoonists. The younger Segar worked as a decorator and house-painter, and played drums accompanying vaudeville acts at the local theatre and – when the town got a movie house – he played for the silent films. This allowed him to absorb the staging, timing and narrative tricks from close observation of the screen, and would become his greatest assets as a cartoonist. It was whilst working as the film projectionist, aged 18, he decided to draw for his living, and tell his own stories.

Like so many from that “can-do” era, Segar studied art via mail: in this case W.L. Evans’ cartooning correspondence course out of Cleveland, Ohio – from where Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster would launch Superman upon the world. Segar gravitated to Chicago and was “discovered” by Richard F. Outcault (The Yellow Kid, Buster Brown), arguably the inventor of newspaper comics.

Outcault introduced Segar around at the prestigious Chicago Herald and soon – still wet behind the ears – Segar’s first strip Charley Chaplin’s Comedy Capers debuted on 12th March 1916. Two years, Elzie married Myrtle Johnson and moved to Hearst’s Chicago Evening American to create Looping the Loop. Managing Editor William Curley saw a big future for Segar and promptly packed the newlyweds off to the Manhattan headquarters of the mighty King Features Syndicate.

Within a year Segar was producing Thimble Theatre for the New York Journal. In 1924, Segar created a second daily strip. The 5:15 was a surreal domestic comedy featuring weedy commuter/would-be inventor John Sappo …and his formidable, indomitable wife Myrtle (!).

A born storyteller, Segar had from the start an advantage even his beloved cinema couldn’t match. His brilliant ear for dialogue and accent shone out from his admittedly average melodrama adventure plots, adding lustre to stories and gags he always felt he hadn’t drawn well enough. After a decade or so – and just as cinema caught up with the introduction of “talkies” – he finally discovered a character whose unique sound and individual vocalisations blended with a fantastic, enthralling nature to create a literal superstar.

Incoherent, plug-ugly and stingingly sarcastic, Popeye shambled on stage midway through ‘Dice Island’ and once his very minor part played out, simply refused to leave. Within a year he was a regular. As circulation skyrocketed, he became the star.

In the less than 10 years Segar worked with his iconic sailor-man (January 1929 until the artist’s untimely death on 13th October 1938), the auteur constructed an incredible meta-world of fabulous lands and lost locales, where unique characters undertook fantastic voyages spawned or overcame astounding scenarios and experienced big, unforgettable thrills as well as the small human dramas we’re all subject to.

This was a saga both extraordinary and mundane, which could be hilarious or terrifying – frequently at the same time. For every trip to the rip-roaring Wild West or lost kingdom, there was a brawl between squabbling neighbours, spats between friends or disagreements between sweethearts – any and all usually settled with mightily-swung fists.

Popeye is the first Superman of comics, but he was not a comfortable hero to idolise. A brute who thought with his fists, lacking all respect for authority, he was uneducated, short-tempered and – whenever hot tomatoes batted their eyelashes (or thereabouts) at him – fickle: a worrisome gambling troublemaker who wasn’t welcome in polite society… and wouldn’t want to be.

The mighty marine marvel is the ultimate working-class hero: raw and rough-hewn, practical, with an innate and unshakable sense of what’s fair and what’s not, a joker who wants kids to be themselves – but not necessarily “good” – and someone who takes no guff from anybody. Always ready to defend the weak and with absolutely no pretensions or aspirations to rise above his fellows, he was and will always be “the best of us”…

This current tranche of reprinted classics concentrates on the astounding full-page Sunday outings (here encompassing March 6th 1932 to November 1933, but sadly omits the absurdist Sappo toppers. You’ll need to track down Fantagraphics’ hardback tabloid collections from a decade ago to see those whacky shenanigans…

Since many papers only carried dailies or Sundays, but only occasionally both, a system of differentiated storylines developed early in American publishing, and when Popeye finally made his belated sabbath day move, he was already a well-developed character.

Ham and Castor had been the stars since Thimble Theatre’s Sundays since the ancillary feature began on January 25, 1925; they all but vanished once the mighty matelot stormed that stronghold. From then on, Segar concentrated on gag-based extended dramatic serials Mondays to Saturdays, leaving family-friendly japes for Sundays: an arena perfect for the Popeye-Olive Oyl modern romance to unfold. With this second volume, however, we get to play with Segar’s second greatest character creation: morally maladjusted master moocher J Wellington Wimpy…

Preceding the vintage views, this tome offers a lovely laudatory comic strip deconstruction, demystification and appreciation in ‘“Segar’s Wimpy” – An Introduction by Kevin Huizenga’. The experimental fabulist (Glen Ganges in The River At Night, Comix Skool USA, Riverside Companion) probes everything from how different illustrators handle the human dustbin to how Wimpy’s eyes are drawn…

When the wondrous weekend instalments began last volume, we saw Ham Gravy gradually edged out of romancing Olive. From there onwards, done-in-one gag instalments outlined an unlikely but enduring romance which blossomed (withered, bloomed, withered some more, hit cold snaps and early harvests – you get the idea…) as Olive alternately pursued her man and dumped him for better prospects.

To be fair, Popeye always vacillated between ignoring her and moving mountains to impress her. Since she always kept her options open, he spent a lot of time fighting off – quite literally – her other gentlemen callers. A mercurial creature, the militantly maidenly Miss Oyl spent as long trying to stop her beau’s battles (a tricky proposition as he spent time ashore as an extremely successful “sprize fighter”) as civilise her man, yet would mercilessly batter any flighty floozy who cast cow eyes at her devil-may-care suitor…

In those formative episodes, Castor became Popeye’s manager and we revelled in how originally-philanthropic millionaire Mr. Kilph moved from eager backer to demented arch enemy paying any price to see Popeye pummelled. The sailors’ opponents included husky two-fisted Bearcat, Mr. Spar, Kid Sledge, Joe Barnacle, Kid Smack, Kid Jolt, The Bullet, Johnny Brawn, an actual giant dubbed Tinearo and even trained gorilla Kid Klutch.

None were tough enough and Kilph got crazier and crazier…

History repeated itself when a lazy and audaciously corrupt ring referee was introduced as a passing bit player. The unnamed, unprincipled scoundrel kept resurfacing and swiping more of the limelight: graduating from minor moments in extended, trenchant, scathingly witty sequences about boxing and human nature to speaking – and cadging – roles…

Among so many timeless supporting characters, mega moocher J. Wellington Wimpy stands out as the complete antithesis of feisty big-hearted Popeye, but unlike any other nemesis I can think of, this black mirror is not an “emeny” of the hero, but his best – maybe only – friend…

As previously stipulated, the engaging Mr. Micawber-like coward, moocher and conman debuted on 3rd May 1931 as an unnamed referee officiating a bombastic month-long bout against Tinearo. He struck a chord with Segar who made him a (usually unwelcome) fixture. Eternally, infernally ravenous and always soliciting (probably on principle) bribes of any magnitude, we only learned the crook’s name in the May 24th instalment. The erudite rogue uttered the first of many immortal catchphrases a month later.

That was June 21st – but “I would gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today” – like most phrases everybody knows, actually started as “Cook me up a hamburger, I’ll pay you Thursday”. It was closely followed by my personal mantra “lets you and him fight”…

Now with a new volume and another year, we open with more of the same. The romantic combat between Olive, Popeye and a string of rival suitors continues, resulting in the sailor winning a male beauty contest (by force of arms), and brutally despatching a procession of potential boyfriends.

As hot-&-cold Olive warms to the moocher, there’s more of Wimpy’s ineffable wisdom on show, as he reinvents himself as the final arbiter of (strictly negotiable) judgement…

Whether it’s her beaux or who’s hardest hit by government policies – sailors like Popeye or restaurant owners like Rough-House – Wimpy has opinions he’s happy to share… for a price.

Mr. Kilph turns up again, arranging a bout between Popeye and his new million-dollar robot, but even with Wimpy officiating, the sailor comes up trumps. The moocher briefly becomes our matelot’s best pal, but blows it by putting the moves on Olive after tasting her cooking…

Another aspect of Popeye’s complex character is highlighted in an extended sequence running from May 29th through July 17th1932, one that secured his place in reader’s hearts.

The sailor was a rough-hewn orphan who loved to gamble and fight. He was proudly not smart and superhumanly powerful, but he was a big-hearted man with an innate sense of decency who hated injustice – even if he couldn’t pronounce it.

When starving waif Mary Ann tries to sell him a flower, Popeye impetuously adopts her, inadvertently taking her from the brutal couple who use her in a begging racket.

Before long the kid is beloved of his entire circle – even Olive – and to support her, Popeye takes on another prize fight: this time with savage Kid Panther and his unscrupulous manager Gimbler…

He grows to truly love her and there’s a genuine sense of happy tragedy when he locates her real and exceedingly wealthy parents. Naturally Popeye gives her up…

That such a rambunctious, action-packed comedy adventure serial could so easily turn an audience into sobbing, sentimental pantywaists is a measure of just how great a spellbinder Segar was. Although rowdy, slapstick cartoon violence remained at a premium – family values were different then – Segar’s worldly, socially- probing satire and Popeye’s beguiling (but relative) innocence and lack of experience keeps the entire affair in hilarious perspective whilst confirming him as an unlikely and lovable innocent, albeit one eternally at odds with cops and rich folk…

Following weeks of one-off gags – like Olive improbably winning a beauty contest and a succession of hilarious Wimpy episodes (such as cannily exposing himself to score burgers from embarrassed customers and ongoing problems with sleep-eating) – a triptych of plot strands opens as Miss Oyl engages a psychiatrist to cure Popeye of fighting, even as the sailor discovers Wimpy has such an affinity with lower life forms that he can be used to lure all the flies and sundry other bugs from Rough-House’s diner…

The third strand has further-reaching repercussions. Popeye has been teaching kids to fight and avoid spankings which has understandably sparked a riot of rebellion, bad behaviour and bad eating habits. Now, distraught parents need Popeye to set things right again…

Naturally it goes too far once the hero-worshipping kids start using the sailor-man as a source of alt-fact schooling too…

We constantly see softer sides of the sailor-man as he repeatedly gives away most of what he earns – to widows and “orphinks” – and exposes his crusading core with numerous assaults on bullies, animal abusers and romantic rivals, but when the war of nerves and resources between Wimpy and Rough-House inevitably escalates, Popeye implausibly finds himself as “the responsible adult”.

That means being referee in a brutal and ridiculous grudge match settled in the ring, with all proceeds going to providing poor kids with spinach. The bout naturally settles nothing but does have unintended consequences when the moocher is suddenly reunited with his estranged mother after 15 years…

Tough men are all suckers for a sob story and even Rough-House foolishly amplifies the importance and regard people supposedly feel for the now-homeless little old lady’s larcenous prodigal. It’s a move the moocher can’t help but exploit…

As the Sunday Pages followed a decidedly domestic but rowdily riotous path, the section was increasing given over to – or more correctly, appropriated – by the insidiously oleaginous Wimpy: an ever hungry, intellectually stimulating, casually charming and usually triumphant conman profiting in all his mendicant missions.

Whilst still continuing Popeye’s pugilistic shenanigans , the action of the Sunday strips moved away from him hitting quite so much to alternately being outwitted by the unctuous moocher or saving him from the vengeance of the furious diner-owner and passionately loathing fellow customer George W. Geezil. The soup-slurping cove began as an ethnic Jewish stereotype, but like all Segar’s characters swiftly developed beyond his (now so offensive) comedic archetype into a unique person with his own story… and another funny accent. Geezil was the chief and most vocal advocate for murdering the insatiable sponger…

Wimpy was incorrigible and unstoppable – he even became a rival suitor for Olive Oyl’s unappealingly scrawny favours – and his development owes a huge debt to his creator’s love and admiration of comedian W.C. Fields.

A mercurial force of nature, the unflappable mendicant is the perfect foil for common-man-but-imperfect-hero Popeye. Where the sailor is heart and spirit, unquestioning morality and self-sacrifice, indomitable defiance, brute force and no smarts at all, Wimpy is intellect and self-serving greed, freed from all ethical restraint or consideration, and gloriously devoid of impulse-control.

Wimpy literally took candy from babies and food from the mouths of starving children, yet somehow Segar made us love him. He is Popeye’s other half: weld them together and you have an heroic ideal… (and yes, those stories are all true: Britain’s Wimpy burger bar chain was built from the remnants of a 1950s international merchandising scheme seeking to put a J Wellington Wimpy-themed restaurant in every town and city).

The gags and exploits of the two forces of human nature build riotously in 1933, ever-more funny and increasingly outrageous.

Having driven Rough-House into a nervous collapse, plundered farms, zoos and the aquarium and committed criminal impersonation and actual fraud, Wimpy then relentlessly targets the cook’s business partner Mr. Soppy: bleeding him dry as visiting royalty Prince Wellington of Nazilia…

Even being run out of town and beaten so badly that he’s repeatedly hospitalised can’t stop his crafty contortions. He does, however, discover a useful talent: musical gifts that all but enslave his audiences…

Eventually, the master beggar triumphs over all and gets to eat his fill… and must deal with the consequences of his locust-like consumption…

Popeye seems unable to stop him. Half the time he’s helpless with laughter at the moocher’s antics, and when not. there are his major prize fights with 500lb wrestler Squeezo Crushinski and human dinosaur Bullo Oxheart. Naturally Wimpy is referee for both those clashes of the titans and makes out like a bandit…

The only real pause to the seeming dominance of the schemer is when he falls for new diner waitress Lucy Brown. She’s currently spending all her time with manly stud Popeye, but a quiet word with Olive Oyl should have cleared Wimpy’s path.

Should have, but didn’t, and in truth results in Popeye and Olive opening their own eatery in competition with Rough-House, leading to a ruthless cutthroat culinary cold war with the polite parasite reaping the spoils…

The laugh-out-loud antics seem impossible to top, and maybe Segar knew that. He was getting the stand-alone gag-stuff out of his system: clearing the decks and setting the scene for a really big change….

These tales are as vibrant and compelling now as they’ve ever been and comprise a world classic of graphic literature that only a handful of creators have ever matched. Within weeks (or for us, next volume) the Thimble Theatre Sunday page changed forever. In a bold move, the dailies blood-and-thunder adventure serial epics traded places with the Sunday format: transferred to the Technicolor “family pages” splendour where all stops might be pulled out…

Segar famously considered himself an inferior draughtsman – most of the world disagreed and still does – but his ability to weave a yarn was unquestioned, and grew to astounding and epic proportions in these strips. Week after week he was creating the syllabary and graphic lexicon of a brand-new art-form: inventing narrative tricks and beats that generations of artists and writers would use in their own cartoon creations. Despite some astounding successors in the drawing seat, no one has ever bettered Segar’s Popeye.

Popeye is fast approaching his centenary and well deserves his place as a world icon. How many comics characters are still enjoying new adventures 94 years after their first? These volumes are the perfect way to celebrate the genius and mastery of E.C. Segar and his brilliantly flawed superman. These are tales you’ll treasure for the rest of your life and superb books you must not miss…

Popeye volume 2: Wimpy and His Hamburgers is copyright © 2022 King Features Syndicate, Inc./™Hearst Holdings, Inc. This edition © 2022 Fantagraphics Books Inc. Segar comic strips provided by Bill Blackbeard and his San Francisco Academy of Comic Art. “Segar’s Wimpy” © 2022 Kevin Huizenga. All rights reserved.