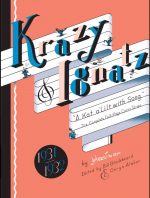

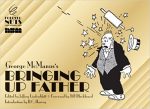

By George McManus, edited by Jeffrey Lindenblatt (NBM)

ISBN 13: 978-1-56163-556-6

One of the best and most influential comic strips of all time gets a wonderfully lavish deluxe outing thanks to the perspicacious folk at NBM as part of their series collecting the earliest triumphs of sequential cartooning. Look out for Happy Hooligan and hunt down Forever Nuts: Mutt and Jeff to see the other strips that formed the basis and foundation of our entire industry and art-form.

George McManus was born on January 23rd 1882 (or maybe 1883) and drew from a very young age. His father, realising his talent, secured him work in the art department of the St. Louis Republic newspaper. The lad was thirteen, and swept floors, ran errands, drawing when ordered to.

In an era before cheap and reliable photography, artists illustrated news stories; usually disasters, civic events and executions: McManus claimed that he had attended 120 hangings – a national record! The young man spent his off-hours producing cartoons and honing his mordant wit. His first sale was Elmer and Oliver. He hated it.

The jobbing cartoonist had a legendary stroke of luck in 1903. Acting on a bootblack’s tip, he placed a $100 bet on a 30-1 outsider and used his winnings to fund a trip to New York City. He splurged his windfall wager and on his last day in the big city got two job offers: one from the McClure Syndicate and a lesser bid from Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

He took the smaller offer, went to work for Pulitzer and created a host of features for the paper including Snoozer, The Merry Marceline, Ready Money Ladies, Cheerful Charlie, Panhandle Pete, Let George Do It, Nibsy the Newsboy in Funny Fairyland (one of the earliest Little Nemo knock-offs) and eventually, his first big hit (1904) The Newlyweds.

This last brought him to the attention of Pulitzer’s arch rival William Randolph Hearst who, acting in tried and true manner, lured the cartoonist away with big money in 1912. In Hearst’s stable of papers The Newlyweds became Sunday page feature Their Only Child, and was soon supplemented by Outside the Asylum, The Whole Blooming Family, Spare Ribs and Gravy and Bringing Up Father.

At first it alternated with other McManus domestic comedies in the same slot, but eventually the artist dropped Oh, It’s Great to be Married!, Oh, It’s Great to Have a Home and Ah Yes! Our Happy Home! as well as his second Sunday strip Love Affairs of a Muttonhead to fully concentrate on the story of Irish hod-carrier Jiggs whose vast newfound wealth brought him no joy, whilst his parvenu wife Maggie and their inexplicably beautiful, cultured daughter Nora sought acceptance in “Polite Societyâ€.

The strip turned on the simplest of premises: whilst Maggie and Nora feted wealth and aristocracy, Jiggs, who only wanted to booze, schmooze and eat his beloved corned beef and cabbage, would somehow shoot down their plans – usually with severe personal consequences. Maggie might have risen in society, but she never lost her devastating accuracy with crockery and household appliances…

Bringing Up Father debuted on January 12th 1913, originally appearing thrice-weekly, then four and eventually every day. It made McManus two fortunes (the first he lost in the 1929 Stock Market crash), spawned a radio show, a movie in 1928, and five more between 1946-1950 (as well as an original Finnish film in 1939) and 9 silent animated short features.

…And that’s not counting all the assorted marketing paraphernalia that fetches such high prices in today’s antique markets. The artist died in 1954, and other creators continued the strip until May 28th 2000, its unbroken 87 years making it the second longest running newspaper strip of all time.

McManus said that he got the basic idea from The Rising Generation: a musical comedy he’d seen as a boy: but the premise of wealth not bringing happiness was only the barest foundation of the strip’s explosive success. Jigg’s discomfort at his elevated position, his yearnings for the nostalgic days and simple joys of youth are afflictions everybody is prey to, but the true magic at play here is the canny blend of slapstick, satire, sexual politics and fashion, all delivered by a man who could draw like an angel. The incredibly clean, simple lines and superb use – and implicit understanding – of art nouveau and art deco imagery and design make this series a stunning treat for the eye.

This magical monochrome hardback – collecting the first two years of Bringing Up Father – covers the earliest inklings of the formation of that perfect formula, and includes a fascinating insight into the American head-set as the fictional and fabulously fractious family go on an extended (eight month) grand tour of the Continent in the months leading up to the Great War.

Then, as 1914 closed, the feature highlights how ambivalent the New World still was to the far-distant “European Warâ€â€¦

An added surprise for a strip of this vintage is the great egalitarianism of it. Although there is an occasional visual stereotype to swallow and excuse, what we today regard as racism is practically absent. The only thing to watch out for is the genteel sexism and dramatically entrenched class (un)consciousness, although McManus clearly pitched his tent on the side of the dirty, disenfranchised and downtrodden – as long as he could get a laugh out of it…

This is a wonderful, evocative celebration of the world’s greatest domestic comedy strip, skilfully annotated for those too young to remember those days and still uproariously funny. Get it for grandma and swipe it while she’s sleeping off the sherry and nostalgia…

No © invoked.