By Crockett Johnson (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-522-8 (HB)

This is one of those books that’s worthy of two reviews, so if you’re in a hurry…

Buy Barnaby now – it’s one of the most wonderful strips of all time and this superb hardcover compilation – and its digitised equivalent – has lots of fascinating extras. If you harbour any yearnings for the lost joys of childish glee and simpler, more clear-cut world-ending crises, you would be crazy to miss this book…

However, if you’re still here and need a little more time to decide…

As long ago as August 2007 I started whining that one of the greatest comic strips of all time was criminally out of print and in desperate need of a major deluxe re-issue. So – as if by the magic of a fine Panatella… Cushlamocree! – Fantagraphics came to my rescue…

Today’s newspapers – those that still cling on by an ink-stained fingernail – have precious few continuity drama or adventure strips. Indeed, if a paper has any strips, as opposed to single panel editorial cartoons at all, chances are they will be of the episodic variety typified by Jim Davis’ Garfield or Scott Adams’ Dilbert – or reruns of old favourites like Calvin and Hobbes or Peanuts.

You can describe most of these as single-idea pieces with a set-up, delivery and punch-line, rendered in sparse, pared-down-to-basics drawing style. In that they’re nothing new. Narrative impetus comes from the unchanging characters themselves, and a building of gag-upon-gag in extended themes. The advantage to the newspaper was obvious. If readers liked a strip it encouraged them to buy the paper. If one missed a day or two, they could return fresh at any time having, in real terms, missed nothing.

Such was not always the case, especially in America. Once upon a time the Daily “funny†– comedic or otherwise – was a crucial circulation builder and preserver, with lush, lavish and magnificently rendered fantasies or romances rubbing shoulders with thrilling, moody masterpieces of crime, war, sci-fi and everyday melodrama. Even the legion of humour strips actively strived to maintain an avid, devoted following.

And eventually there was Barnaby which in so many ways bridged the gap between then and now…

On April 20th 1942, with America at war for the second time in 25 years, liberal New York tabloid PM (a later iteration of which – The New York Star – debuted Walt Kelly’s wonderful Pogo) began running a new, sweet strip for kids which was the most whimsically addicting, socially seditious and ferociously smart satire since the creation of Al Capp’s Li’l Abner – another complete innocent left to the mercy of scurrilous worldly influences…

The outlandish 4-panel Daily, by Crockett Johnson, was the brainchild of a man who didn’t particularly care for comics, but who – according to celebrated strip historian Ron Goulart – just wanted steady employment…

David Johnson Leisk (October 20th 1906-July 11th 1975) was an ardent socialist, passionate anti-fascist, gifted artisan and brilliant designer who had spent much of his working life as a commercial artist, Editor and Art Director.

Born in New York City and raised in the outer borough of Queens (when it was still semi-rural – very near the slag heaps which would eventually house two New York World’s Fairs in Flushing Meadows) Leisk studied art at Cooper Union (for the Advancement of Science and Art) and New York University before leaving early to support his widowed mother. This entailed embarking upon a hand-to-mouth career drawing and constructing department-store advertising.

He supplemented that income with occasional cartoons to magazines such as Collier’s before becoming an Art Editor at magazine publisher McGraw-Hill. He also began producing a moderately successful, “silent†strip called The Little Man with the Eyes.

Johnson had divorced his first wife in 1939 and moved out of the city to Connecticut, sharing an ocean-side home with student (and eventual bride) Ruth Krauss, always looking to create that steady something, when, almost by accident, he devised a masterpiece of comics narrative…

However, if his friend Charles Martin hadn’t seen a prototype Barnaby half-page lying around the house, the series might never have existed. Happily, Martin hijacked the sample and parlayed it into a regular feature in prestigious highbrow leftist tabloid PM simply by showing the scrap to the paper’s Comics Editor, Hannah Baker.

Among her other finds was a strip by a cartoonist dubbed Dr. Seuss which would run contiguously in the same publication. Despite Johnson’s initial reticence, within a year Barnaby had become the new darling of the intelligentsia…

Soon there were hard-back book collections, talk of a Radio show (in 1946 it was adapted as a stage play), rave reviews in Time, Newsweek and Life. The small but rabid fan-base ranged from politicians and the smart set such as President and First Lady Roosevelt, Vice-President Henry Wallace, Rockwell Kent, William Rose Benet and Lois Untermeyer to cool celebrities such as Duke Ellington, Dorothy Parker, W. C. Fields and even legendary New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

Of course, the last two might only have checking the paper because the undisputed, unsavoury star of the show was a scurrilous if fanciful amalgam of them both…

Not since George Herriman’s Krazy Kat had a scrap of popular culture so infiltrated the halls of the mighty, whilst largely passing way over the heads of the masses and without troubling the Funnies sections of big circulation papers. Over its 10-year run – from April 1942 to February 1952 – Barnaby was only syndicated to 64 papers nationally, with a combined circulation of just over five and a half million, but it kept Crockett (a childhood nickname) and Ruth in relative comfort whilst America’s Great and Good constantly agitated on the kid’s behalf.

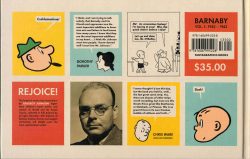

This splendid collection opens with a hearty appreciation from Chris Ware in the Foreword before cartoonist and historian Jeet Heer provides a critical appraisal in ‘Barnaby and American Clear Line Cartooning’, after which the captivating yarn-spinning takes us from April 20th 1942 to December 31st 1943.

There’s even more elucidatory content after that, though, as education scholar and Professor of English Philip Nel provides a fact-filled, picture-packed ‘Afterword: Crockett Johnson and the Invention of Barnaby’; Dorothy Parker’s original ‘Mash Note to Crockett Johnson’ is reprinted in full, and Nel also supplies strip-by-strip commentary and background in ‘The Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, and Little Men’s Chowder & Marching Society: a Handy Pocket Guide’…

The real meat begins with the strip itself and starts when ‘Mr. O’Malley Arrives’. This ran from 20th to 29th April 1942, setting the ball rolling as a little boy wishes one night for a Fairy Godmother and something strange and disreputable falls in through his window…

Barnaby Baxter is a smart, ingenuous and scrupulously honest pre-schooler (4-year-old to you) whose ardent wish is to be an Air Raid Warden like his dad. Instead he is “adopted†by a short, portly, pompous, mildly unsavoury and wholly discreditable windbag with pink wings.

Jackeen J. O’Malley, card carrying-member of the “Elves, Gnomes, Leprechauns and Little Men’s Chowder and Marching Society†– although he hasn’t paid his dues in years – installs himself as the lad’s Fairy Godfather. A lazier, more self-aggrandizing, mooching old glutton and probable soak (he certainly frequents taverns but only ever raids the Baxter’s icebox, pantry and humidor, never their drinks cabinet…) could not be found anywhere.

Due more to intransigence than evidence – there’s always plenty of physical proof whenever O’Malley has been around – Barnaby’s father and mother adamantly refuse to believe in the ungainly, insalubrious sprite, whose continued presence hopelessly complicates the sweet boy’s life. The poor parents’ greatest abiding fear is that Barnaby is cursed with Too Much Imagination…

In fact, this entire glorious confection is about our relationship to imagination. This is not a strip about childhood fantasy. The theme here, beloved by both parents and children alike, is that grown-ups don’t listen to kids enough, and that they certainly don’t know everything.

Despite looking like a fraud – he never uses his magic and always wields one of Dad’s stolen cigars as a substitute wand – O’Malley is the real deal: he’s just incredibly lazy, greedy, arrogant and inept. He does – sort of – grant Barnaby’s wish though, as his midnight travels in the sky trigger a full air raid alert in ‘Mr. O’Malley Takes Flight’ (30th April-14th May)…

‘Mr. O’Malley’s Mishaps’ (15th-28th May) offer further insights into the obese elf’s character – or lack of same – as Barnaby continually fails to convince his folks of his newfound companion’s existence, before the bestiary expands into a topical full-length adventure when the little guys stumble into a genuine Nazi plot with supernatural overtones in the hilariously outrageous ‘O’Malley vs. Ogre’ – which ran from 29th May through 31st August.

‘Mr. O’Malley’s Malady’ (1st – 11th September) deals with the airborne oaf’s brief bout of amnesia, even as Mum and Dad, believing their boy is acting up, take him to a child psychologist. However, ‘The Doctor’s Analysis’ (12th – 24thSeptember) doesn’t help…

The war’s effect on the Home Front is an integral part of the strip and ‘Pop vs. Mr. O’Malley’ (25th September – 6thOctober) and ‘The Test Blackout’ (7th – 16th October) see Mr. Baxter become chief Civil Defense Coordinator despite – not because of – the winged interloper, but not without suffering the usual personal humiliation.

There is plenty to go around and, when ‘The Invisible McSnoyd’ (17th – 31st October) turns up, O’Malley gets it all.

The Brooklyn Leprechaun, although unseen, is O’Malley’s personal gadfly: continually barracking, offering harsh, ribald counterpoints and home truths to the Godfather’s self-laudatory pronouncements, and in ‘The Pot of Gold’ (2nd – 20thNovember) perpetually taunting and tempting JJ to provide a treasure trove of laughs…

When Barnaby wins a scrap-metal finding competition and is feted on radio, O’Malley co-opts ‘The Big Broadcast’ (21st – 28th November) and brings chaos to the airwaves, but once again Mr. Baxter won’t believe his senses. Dad’s situation only worsens after ‘The New Neighbors’ (30th November – 16th December) move in and little Jane Shultz also starts candidly reporting Mr. O’Malley’s deeds and misadventures…

Barnaby’s faith is only near-shaken when the Fairy Fool’s constant prevarications and procrastination mean Dad Baxter’s Christmas present arrives late. The Godfather did accidentally destroy an animal shelter in the process, so ‘Pop is Given a Dog’ (17th – 30th December) which brings a happy resolution of sorts…

A perfect indication of the wry humour that peppered the feature can be seen in ‘The Dog Can Talk’ – which ran from 31stDecember 1942 to 17th January 1943. New pooch Gorgon can indeed converse – but never when the parents are around, and only then with such overwhelming dullness that everybody listening wishes him as mute as all other mutts…

Playing in an old abandoned house (don’t you miss those days when kids could wander off for hours, unsupervised by eagle-eyed, anxious parents – or were even able to walk further than the length of a garden?) serves to introduce Barnaby and Jane to ‘Gus, the Ghost’ (18th January to February 4th) which in turn involves the entire ensemble with ration-busting thieves after they uncover ‘The Hot Coffee Ring’ (5th – 27th February). Barnaby is again hailed a public hero and credit to his neighbourhood, even as poor Dad stands back and stares, nonplussed and incredulous…

As Johnson continually expanded his gently bizarre cast of Gremlins, Ogres, Ghosts, Policemen, Spies, Black Marketeers, Talking Dogs and even Little Girls, all of whom can see O’Malley, the unyieldingly faithful little lad’s parents are always too busy and too certain that the Fairy Godfather and all his ilk are unhealthy, unwanted, juvenile fabrications.

With such a simple yet flexible formula Johnson made pure cartoon magic. ‘The Ghostwriter Moves In’ (1st – 11th March) finds Gus reluctantly relocating to the Baxter abode, where he is even less happy to be cajoled into typing out O’Malley’s odious memoirs and organising ‘The Testimonial Dinner’ (12th March – 2nd April) for the swell-headed sprite at the Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, and Little Men’s Chowder & Marching Society clubhouse and pool hall…

With the nation urged to plant food crops, ‘Barnaby’s Garden’ (3rd – 16th April) debuts as a another fine example of the things O’Malley is (not) expert in, whilst ‘O’Malley and the Lion’ (17th April – 17th May) finds the innocent waif offering sanctuary to a hirsute circus star even as his conniving, cheroot-chewing cherub contemplates his own “return†to showbiz, after which ‘Atlas, the Giant’ (18th May – 3rd June) wanders into the serial. At only 2-feet tall, the pint-sized colossus is not that impressive… until he gets out his slide-rule to demonstrate that he is, in fact, a mental giant…

‘Gorgon’s Father’ (4th June – 10th July) turns up to cause contretemps and consternation before disappearing again, after which Barnaby and Jane are packed off to ‘Mrs. Krump’s Kiddie Kamp’ (12th July – 13th September) for vacation rest and the company of normal children.

Sadly, although the wise matron and her assistant never glimpse O’Malley and Gus, all the other tykes and inmates are more than happy to associate with them…

Once the kids arrive back in Queens – Johnson had set the series in the streets where he’d grown up – the Fairy Fool is showing off his “mechanical aptitude†on a parked car with its engine wastefully running and breaks the idling getaway car just in time to foil a robbery…

Implausibly overnight he becomes an unseen and reclusive ‘Man of the Hour’ (14th – 18th September) before preposterously translating that cachet into a political career by accidentally becoming a patsy for a corrupt political machine in ‘O’Malley for Congress!’ (20th September – 8th October).

This strand gave staunchly socialist cynic Johnson ample opportunity to ferociously lampoon the electoral system, the pundits and even the public. Without spending money, campaigning – or even being seen – the pompous pixie wins ‘The Election’ (9th October – 12th November) and actually becomes ‘Congressman O’Malley’ (13th – 23rd November), with Barnaby’s parents perpetually assuring their boy that this guy was not “his†Fairy Godfather’…

The outrageous satire only intensified once ‘The O’Malley Committee’ (24th November – 27th December 1943) began its work – by investigating Santa Claus – despite the newest, shortest Congressman in the House never actually turning up to do a day’s work…

Raucous, riotous sublimely surreal and adorably absurd, the untrammelled, razor-sharp whimsy of the strip is instantly captivating, and the laconic charm of the writing well-nigh irresistible, but the lasting legacy of this ground-breaking feature is the clean, sparse line-work that reduces images to almost technical drawings: unwavering line-weights and solid swathes of black that define space and depth by practically eliminating it, without ever obscuring the fluid warmth and humanity of the characters. Almost every modern strip cartoon follows the principles laid down here by a man who purportedly disliked the medium…

The major difference between then and now should also be noted, however. Johnson despised doing shoddy work, or short-changing his audience. On average each of his daily, always self-contained encounters built on the previous episode without needing to re-reference it, and offered three to four times as much text as its contemporaries. It’s a sign of the author’s ability that the extra wordage is never unnecessary, and often uniquely readable, blending storybook clarity, the snappy pace of “Screwball†comedy films and the contemporary rhythms and idiom of authors such as Damon Runyan.

He managed this miracle by type-setting the dialogue and pasting up the strips himself – primarily in Futura Medium Italic but with effective forays into other fonts for dramatic and comedic effect.

No sticky-beaked educational vigilante could claim Barnaby harmed children’s reading abilities by confusing the tykes with non-standard letter-forms (a charge levelled at comics as late as the turn of this century), and the device also allowed him to maintain an easy, elegant, effective balance of black and white which makes the deliciously diagrammatic art light, airy and implausibly fresh and accessible.

During 1946-1947, Johnson surrendered the strip to friends as he pursued a career illustrating children’s book such as Constance J. Foster’s This Rich World: The Story of Money, but eventually he returned, crafting more magic until he retired Barnaby in 1952 to concentrate on books.

When Ruth graduated she became a successful children’s writer and they collaborated on four tomes – The Carrot Seed(1945), How to Make an Earthquake, Is This You? and The Happy Egg, but these days Crockett Johnson is best known for his seven “Harold†books. These began in 1955 with the captivating Harold and the Purple Crayon.

During a global war with heroes and villains aplenty, where no comic page could top the daily headlines for thrills, drama and heartbreak, Barnaby was an absolute panacea to the horrors without ever ignoring or escaping them.

For far too long, Barnaby was a lost masterpiece. It is influential, ground-breaking and a shining classic of the form. It is also warm, comforting and outrageously hilarious. You are all poorer for not knowing it, and should move mountains to change that situation. I’m not kidding.

Liberally illustrated throughout with sketches, roughs, photos and advertising materials as well as Credits, Thank You and a brief biography of Johnson, this big book of joy will be a welcome addition to 21st century bookshelves – especially yours…

Barnaby and all its images © 2013 the Estate of Ruth Kraus. Supplemental material © 2013 its respective creators and owners.