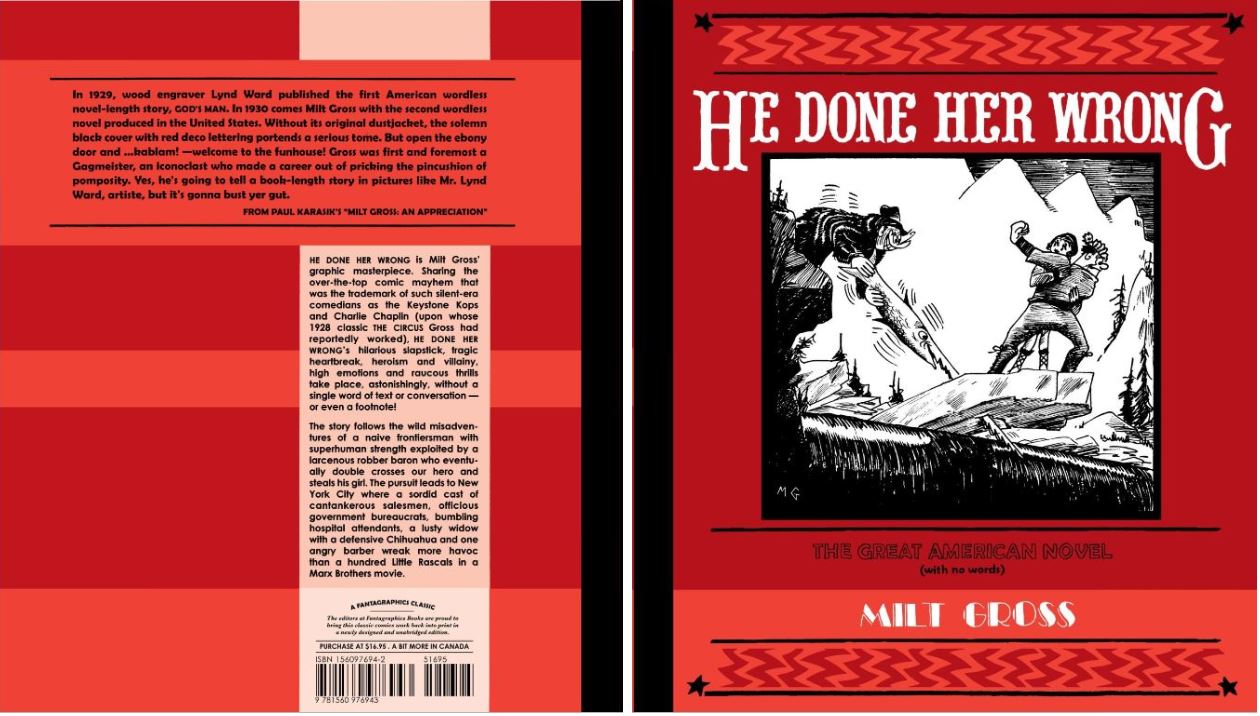

By J.-C. Mézières & P. Christin with colours by E. Tranlê: translated by Jerome Saincantin (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-1-84918-352-9 (HB/Digital edition)

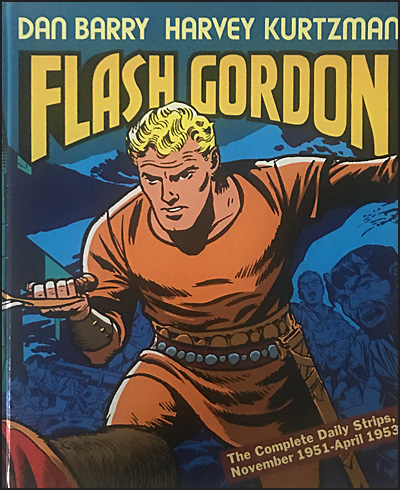

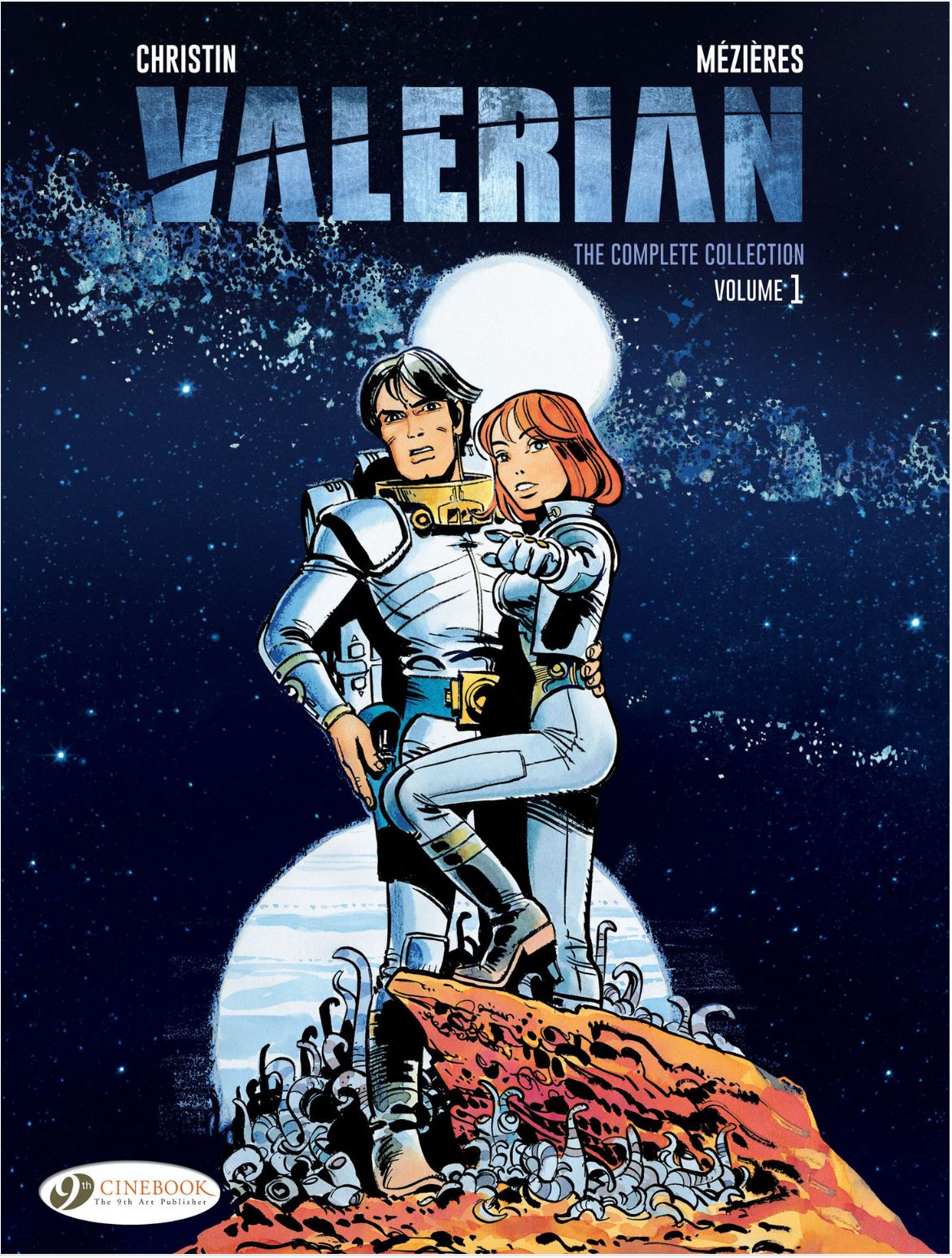

Although I still marginally plump for Flash Gordon, another strong contender for the most influential science fiction series ever drawn – and yes, I am including Buck Rogers in this tautological turmoil – is Valérian. Although to a large extent those venerable newspaper strips actually formed the genre itself, anybody who has seen a Star Wars movie (or indeed any sci fi flic from the 1980s onwards) has seen some of Jean-Claude Mézières & Pierre Christin’s brilliant imaginings which the film industry has shamelessly plundered for decades: everything from the Millennium Falcon’s look to Leia’s Slave Girl outfit…

Please don’t take my word for it: this splendid oversized hardback compendium – originally released to cash in on the epic Luc Besson movie – has a copious and good-natured text feature entitled ‘Image Creators’ confirming and comparing panels to film stills.

In case you’re curious, additional features include photo & design art-packed ‘Interview Luc Besson, Jean-Claude Mézières and Pierre Christin (Part I)’ plus bullet-point historical briefings ‘How it All Began…’, ‘Go West Young Men!’, ‘Colliding Worlds’, ‘Explore Anything’ and ‘Hello!’ This is Laureline…’. Simply put, more carbon-based lifeforms have marvelled at the uniquely innovative, grungy, lived-in tech realism and light-hearted swashbuckling roller-coasting of Mézières & Christin than any other cartoon spacer ever imagined possible.

Valérian: Spatio-Temporal Agent launched in the November 9th 1967 edition of Pilote (#420, running until February 15th 1968). It was an instant hit. However, album compilations only began with second tale The City of Shifting Waters, as all creatives concerned considered their first yarn as a work-in-progress, not quite up to their preferred standard. You can judge for yourself, as that prototype – Bad Dreams – kicks off this volume, in its first English-language translation…

The groundbreaking series was boosted by a Franco-Belgian mini-boom in science fiction triggered by Jean-Claude Forest’s 1962 creation Barbarella. Other notable successes of the era include Greg & Eddy Paape’s Luc Orient and Philippe Druillet’s Lone Sloane tales (our reviews are coming soon!), which all – with Valérian – stimulated mass public reception to science fiction and led to the creation of dedicated fantasy periodical Métal Hurlant in 1977.

Valérian and Laureline (as it became) is a light-hearted, wildly imaginative time-travel adventure-romp (a bit like Doctor Who, but not really at all), drenched in wry, satirical, humanist, political commentary, starring (at least in the beginning) an affably capable but unimaginative, by-the-book cop tasked with protecting universal time-lines and counteracting paradoxes caused by reckless casual time-travellers…

The fabulous fun commences with the aforementioned Bad Dreams – which began life as Les Mauvais Réves – a blend of comedy and action as dry dullard Valérian voyages to 11th century France in pursuit of a demented dream-scientist: a maverick seeking magical secrets to remake the universe to his liking. Sadly, our hero is a little out of his depth until rescued from a tricky situation by a fiery, capable young woman/temporal native called Laureline.

After handily dealing with the dissident Xombul and his stolen sorceries, Valerian brings Laureline back with him to the 28th century super-citadel and administrative wonderland of Galaxity, capital of the vast and mighty Terran Empire.

The indomitable girl trains as a Spatio-Temporal operative and is soon an apprentice Spatio-Temporal Agent accompanying Val on his missions throughout time and space…

Every subsequent Valérian adventure until the 13th was first serialised in weekly Pilote until the conclusion of The Rage of Hypsis (January 1st – September 1st 1985) after which the mind-wrenching sagas were simply launched as all-new complete graphic novels, until the magnificent opus concluded in 2010.

One clarifying note: in the canon, “Hypsis” is counted as the 12th tale, due to collected albums being numbered from The City of Shifting Waters. When Les Mauvais Réves was finally released in a collected edition in 1983 it was given the number #0. The City of Shifting Waters was originally published in two tranches; La Cité des Eaux Mouvantes (#455-468, 25th July – 24th October 1968) followed by Terre en Flammes (Earth in Flames, #492-505, 10th April – 10th July 1969).

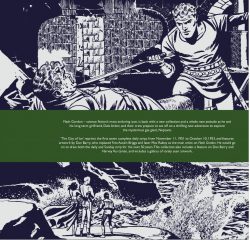

Both are included here and the action opens with the odd couple dispatched to 1986 – when civilisation on Earth was destroyed due to ecological negligence, political chicanery and atomic holocaust. Their orders are to recapture Xombul, still hellbent on undermining Galaxity and establishing himself as Dictator of the Universe. To attain this goal the renegade travelled to New York after the nuclear accident melted the ice caps and flooded the city – and almost everywhere else. He’s hunting lost scientific secrets that would allow him to conquer the devastated planet and prevent the Terran Empire ever forming… at least that’s what his Galaxity pursuers assume…

Plunged back into an apocalyptic nightmare where Broadway and Wall Street are submerged, jungle vines connect deserted skyscrapers, tsunamis are an hourly hazard and bold looters snatch up the last golden treasures of a lost civilisation, the S-T agents find unique allies to preserve the proper past, but are constantly thwarted by Xombul who has constructed deadly robotic slaves to ensure his schemes.

Visually spectacular, mind-bogglingly ingenious and steeped in delicious in-jokes (the utterly-mad-yet-brilliant boffin who helps them is a hilarious dead ringer for Jerry Lewis in 1963 film The Nutty Professor) this is a timelessly witty Science Fiction delight which climaxes in a moody cliffhanger…

Immediately following, Earth in Flames concludes the saga as our heroes head inland, encountering hardy survivors of the holocaust. Enduring more hardships, they escape even greater catastrophes such as the eruption of a super-volcano under Yellowstone Park before finally frustrating the plans of the most ambitious mass-killer in all of history… and as Spatio-Temporal Agents they should know…

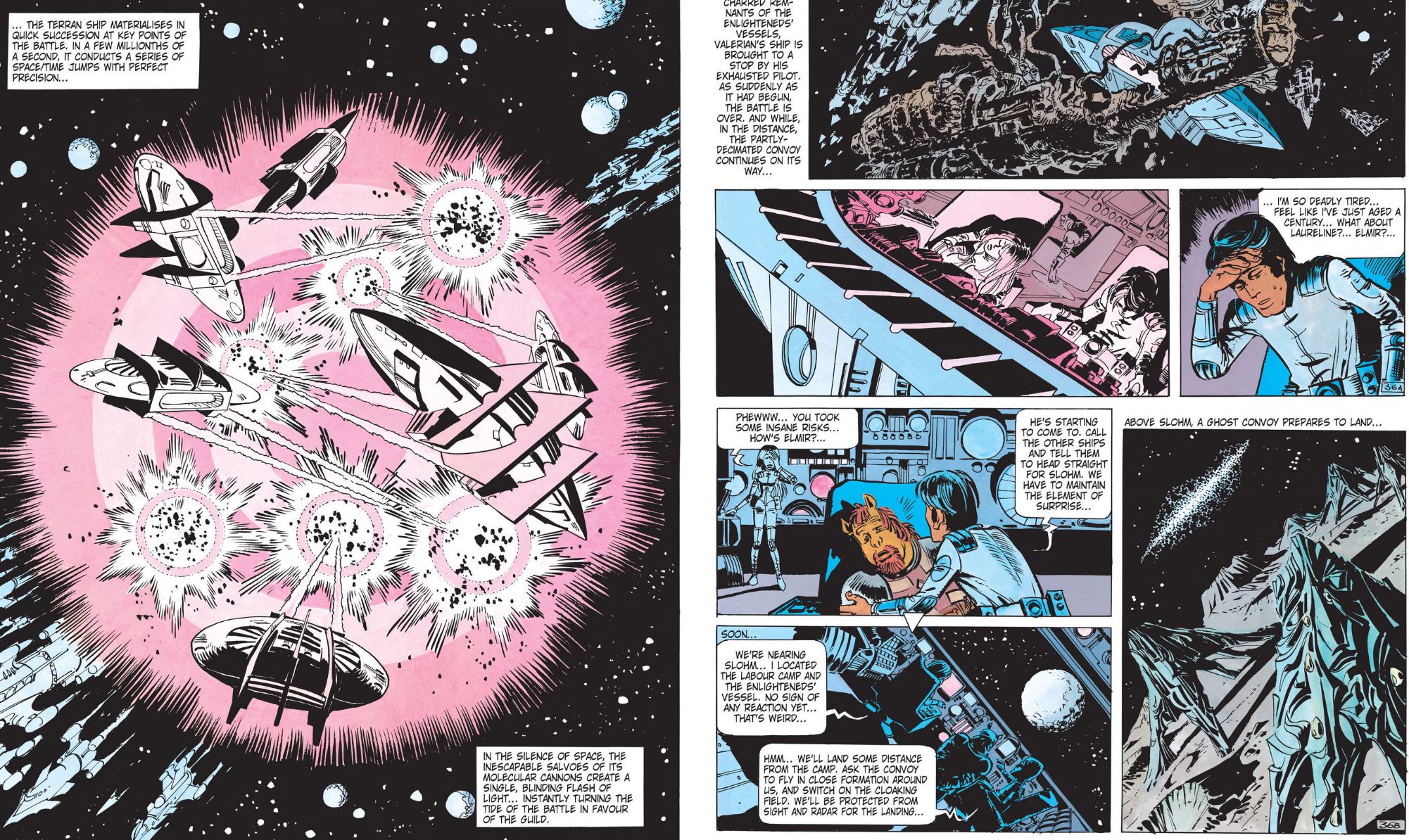

Concluding this first fantastic festive celebration is The Empire of a Thousand Planets (originally seen in Pilote #520-541, October 23rd 1969 – March 19th 1970) as veteran and rookie are despatched to fabled planet Syrte the Magnificent. It is the capital of a vast system-wide civilisation and a world in inexplicable and rapid technological and social decline. The mission is threat-assessment: staying in their base time-period (October 2720) the pair must examine the first galactic civilisation ever discovered which has never experienced any form of human contact or contamination. As usual, events don’t go according to plan…

Despite easily blending into a culture with a thousand separate sentient species, Valerian & Laureline find themselves plunged into intrigue and dire danger when the cheekily acquisitive girl buys an old watch in the market. Nobody on Syrte knows what it is since all the creatures of this civilisation have an innate, infallible time-sense, but the gaudy bauble quickly attracts the attention of one of the Enlightened – a sinister cult of masked mystics who have the ear of the Emperor and a stranglehold on all technologies.

The Enlightened are responsible for the stagnation within this once-vital interplanetary colossus and they quickly move to eradicate the Spatio-Temporal agents. Narrowly escaping doom, the pair reluctantly experience the staggering natural wonders and perils of the wilds beyond the capital city before dutifully returning to retrieve their docked spaceship. Sadly, our dauntless duo are distracted, embroiled in a deadly rebellion fomented by the Commercial Traders Guild. Infiltrating the awesome palace of the puppet-Emperor and visiting the mysterious outer planets, Valerian & Laureline discover a long-fomenting plot to destroy Earth – a world supposedly unknown to anyone in this Millennial Empire…

All-out war looms and the Enlightened’s incredible connection to post-Atomic disaster Earth is revealed just as interstellar conflict erupts between rebels and Imperial forces, with our heroes forced to fully abandon their neutrality and take up arms to save two civilisations a universe apart yet inextricably linked…

Comfortingly familiar and always innovative, this savvy space-opera is fun-filled, action-packed, spectacular, visually breathtaking and mind-bogglingly ingenious. Drenched in wide-eyed fantasy wonderment, science fiction adventures have never been better than this.

© Dargaud Paris, 2016 by Christin, Mézières & Tranlê. All rights reserved. English translation © 2016 Cinebook Ltd.