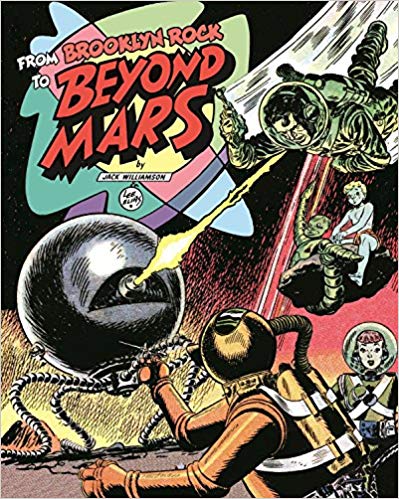

By Jack Williamson & Lee Elias (IDW Publishing)

ISBNs: 978-1-631404-35-1 (HB)

The 1950s was the last great flourish of the American newspaper strip. Invented and always used as a way to boost circulation and encourage consumer loyalty, the inexorable rise of television and spiralling costs of publishing gradually ate away at all but the most popular cartoon features as the decade ended, but the earlier years saw a final, valiant, burst of creativity and variety as syndicates looked for ways to recapture popular attention whilst editors increasingly sought ways to maximise every fraction of a page-inch for paying ads, not fritter the space away with expensive cost-centres. No matter how well produced, imaginative or entertaining, if strips couldn’t increase sales, they weren’t welcome…

The decade also saw a fantastic social change as a commercial boom and technological progress created a new type of visionary consumer – one fired up by the realization that America was Top Dog in the world.

The optimistic escapism offered by the stars above led to a reawakening in the moribund science fiction genre, with a basic introduction for the hoi-polloi offered by the burgeoning television industry through such pioneering (if clunky) programmes as Tom Corbett, Space Cadet or Captain Video and movies from visionaries like Robert Wise (Day the Earth Stood Still) and George Pal (Destination Moon, When Worlds Collide, War of the Worlds and others).

For kids of all ages, conceptual fancies were being tickled by a host of fantastic comicbooks ranging from the blackly satirical Weird Science Fantasy to the affably welcoming and openly enthusiastic Strange Adventures and Mystery in Space. In the inexorably expiring pulp magazines, master imagineers such as Heinlein, Bradbury, Asimov, Clarke, Sturgeon, Dick, Bester and Farmer were transforming the genre from youthful melodrama into a highly philosophical art form…

With Flying Saucers in the skies, Reds under every Bed and refreshing adventure in mind, the multifarious Worlds of Tomorrow were common currency and newspaper strips wanted in on the phenomenon. Established features such as Buck Rogers, Brick Bradford and Flash Gordon were no longer enough and editors demanded bold new visions to draw in a wider public, not just those steady fans who already bought papers for their favourite futurian.

John Stewart “Jack†Williamson was one of the first superstars of American science fiction writing, a rurally raised, self-taught author with more than 50 books, 18 short story collections and even volumes of criticism and non-fiction to his much-lauded name. Born in Arizona in 1908, he was raised in Texas and in 1928 sold his first story to Amazing Stories.

Williamson created a number of legendary serials such as the Legion of Space, The Humanoids and the Legion of Time. He is credited by the OED with inventing the terms and concepts of “terraforming†and “genetic engineering.†He was one of the first literary investigators of anti-matter with his Seetee novels.

“See Tee†or “Contra Terrene Matter†is also at the heart of the strip under discussion here, completely collected in this magnificent full colour volume and available in positive matter Hardback and the ethereal pulses technique we dub digital publication.

Following a damning newspaper review of Seetee Ship, Williamson’s second novel in that sequence – which claimed the book was only marginally better than a comic strip – the editor of a rival paper was moved to engage Williamson and artist Lee Elias to produce a Sunday page based in the same universe as the books.

Leopold Elias was born in England in 1920, but grew up in the USA after his family emigrated in 1926. He studied at the Cooper Union and Art Students League of New York before beginning his professional comics illustration career at Fiction House in 1943. He worked on Captain Wings and latterly western strip Firehair. His sleek, Milton-Caniff-inspired art was soon highly prized by numerous publishers, and Elias contributed to the lustre of The Flash, Green Lantern, Sub-Mariner, Terry and the Pirates and, most notably, the glamourous Black Cat strip for Harvey Comics.

Elias briefly left the funnybook arena in the early 1950s after his art was singled out by anti-comicbook zealot Dr. Fredric Wertham. He traded up to the more prestigious newspaper strips, ghosting Al Capp’s Li’l Abner before landing the job of bringing Beyond Mars to life.

He returned to comicbooks after the strip’s demise, becoming a mainstay at DC in the 1960s, Marvel in the 1970s and Warren in the 1980s. He died in 1998, having spent his final years teaching at the School of Visual Arts and the Kubert School.

The glorious meeting of the minds is preceded here by an effusive and informative Introduction from Bruce Canwell – ‘When “Retro†Was Followed by “Rocket‒ – packed with cover illustrations, original art pages and illustrations that set the scene and share lost secrets of the strips genesis and ultimate Armageddon.

With Dick Tracy strip maestro Chester Gould as adviser for the early days, Beyond Mars ran exclusively and in full colour in the New York Daily News every Sunday from 17th February 1952 to May 13th 1955: a gloriously high-tech, high-adventure romp based around Brooklyn Rock in 2191 AD.

This bastion was a commercial space station bored into one of the rocky chunks drifting in the asteroid belt “Beyond Mars†– the ideal rough-and-tumble story venue on the ultimate frontier of human experience.

Although as the series progressed a progression of sexy women and inspired extraterrestrial sidekicks increasingly stole the show, the notional star is Spatial Engineer Mike Flint, an independent charter-pilot based on the rock, and the first tale begins with Flint selling his services to plucky Becky Starke who has come to the furthest edge of civilisation in search of her missing father. A student of human nature, she cloaks that motivation as a quest for a city-sized, solid diamond asteroid floating in the deadly “Meteor Driftâ€â€¦

Soon Mike and his lisping ophidian Venusian partner Tham Thmith are contending with Brooklyn Rock’s crime boss Frosty Karth, a fantastic raider dubbed the Black Martian, a super-criminal named Cobra and even more unearthly menaces in a stirring tale of interplanetary drug dealers, lost cities, dead civilisations…

There’s even a fantastic mutation in the resilient form of a semi-feral Terran boy who can breathe vacuum and rides deep space on a meteor!

With that tale barely concluded the crew, including the rambunctious space boy Jimikin, fell deep into another mystery – Brooklyn Rock has gone missing!

However, Flint has no time to grieve for the family and friends left behind as he intercepts an inbound star-liner and discovers both an old flame and a smooth-talking thug bound for the now-missing space station. One of them knows where it went…

Unknown to even this mastermind, the Rock, stolen by pirates, is out of control and drifting to ultimate destruction in a debris field, but no sooner is that crisis averted than the heroes are entangled in a “First Contact†situation with an ancient alien from beyond Known Space. Perhaps that might actually be more correctly deemed becoming snared by the devilish devices he/she/it left running…

Ultimately, Mike, Tham, Jimikin and curvaceous Xeno-archeologist Victoria Snow narrowly escape alien vivisection from robotic relics before the tragic, inevitable conclusion…

Snow’s brother Blackie is a fast-talking ne’er-do-well, and when he shows up, old enemy Karth takes the opportunity to try and settle some old scores, leading Flint into a deadly trap on Ceres and a slick saga of genetic manipulation, eugenic supermen and bonanza wealth…

Meanwhile on an interplanetary liner, a new cast member “resurfaces†in the shape of crusty old coot – and Mercurian ore prospector – Fireproof Jones, just in time to help Flint and Sam mine their newfound riches.

As ever, Karth is looking to make trouble for the heroes but he wins some for himself when his young daughter suddenly turns up on the Rock, accompanied by gold-digging Pamela Prim. Suddenly, the murderous raider Black Martian returns to plague the honest pioneers of the Brooklyn frontier…

Glamour model Trish O’Keefe causes a completely different kind of trouble when she lands, looking for her fiancé. Naturally, Tack McTeak isn’t the humble space-doctor he claims to be but is a cerebrally augmented criminal mastermind, and his plans to snatch the biggest prize in space lead to a sequence of stunning thrills and astonishing action.

The scene switches to Earth as the cast visit “civilisation†and find it far from hospitable, so the chance to battle manufactured monsters and the mysterious Dr. Moray on his private tropical island is something of a welcome – if mixed – blessing.

By this time, the writing must have been on the wall, as the strip had been reduced to a half page per week. Even so, the creators clearly decided to go out in style. The sheer bravura spectacle was magnificently ramped up and all the tools of the science fiction trade were utilized to ensure the strip ended with a bang. Moray’s plans are catastrophically realised when the villain employs an anti-gravity bomb to steal Manhattan; turning it into a deadly Sword of Damocles in the sky…

The series abruptly ended when the New York Daily News changed its editorial policy: dropping all comics from its pages. The decision was clearly unexpected, as the saga finished satisfactorily but quite abruptly on Sunday 13th March 1955.

Beyond Mars is a breathtaking lost gem from two master craftsmen that successfully blended the wonders of science and the rollicking thrills of Westerns with broad, light-hearted humour to produce a mind-boggling, eye-popping, exuberantly wholesome family space-opera the likes of which wouldn’t be seen again until Star Wars put the fun back into futuristic fiction.

Thankfully, after years of frustrated agitation by fans, the entire saga has been collected into a this beautiful oversized (244 x 307 mm) hardback edition that no lover of futuristic fun and frolics can afford to be without.

© 2015 Tribune Content Agency LLC. All rights reserved. Introduction © 2015 Bruce Canwell.