By Tim Barela (Palliard Press)

ISBN: 978-1-88456-805-3 (Album PB)

We live in an era where Pride events are world-wide and commonplace: where acceptance of LGBTQIA+ citizens is a given… at least in all the civilised countries where dog-whistle politicians, populist “hard men” totalitarian dictators (I’m laughing at a private dirty joke right now) and sundry organised religions are kept in their generally law-abiding places by their hunger for profitable acceptance and desperation to stay tax-exempt, scandal-free, rich and powerful.

There’s still too many places where it’s not so good to be Gay but at least Queer themes and scenes are no longer universally illegal and can be ubiquitously seen in entertainment media of all types and age ranges… and even on the streets of most cities. For all the injustices and oppressions, we’ve still come a long, long way and it’s and simply No Big Deal anymore. Let’s affirm that victory and all work harder to keep it that way…

Such was not always the case and, to be honest, the other team (with religions proudly egging them on and backing them up) are fighting hard and dirty to reclaim all the intolerant high ground they’ve lost thus far.

Incredibly, all that change and counteraction happened within the span of living memory (mine, in this case). For English-language comics, the shift from illicit pornography to homosexual inclusion in all drama, comedy, adventure and other genres started as late as the 1970s and matured in the 1980s – despite resistance from most western governments – thanks to the efforts of editors like Robert Triptow and Andy Mangels and cartoonists like Howard Cruse, Vaughn Bode, Trina Robbins, Lee Marrs. Gerard P. Donelan, Roberta Gregory, Touko Valio Laaksonen/“Tom of Finland” and Tim Barela.

A native of Los Angeles, Barela was born in 1954, and became a fundamentalist Christian in High School. He loved motorbikes and had dreams of becoming a cartoonist. He was also a gay kid struggling to come to terms with what was still judged illegal, wilfully mind-altering psychosis and perversion – if not actual genetic deviancy – and an appalling sin by his theological peers and close family…

In 1976, Barela began an untitled comic strip about working in a bike shop for Cycle News. Some characters then reappeared in later efforts Just Puttin (Biker, 1977-1978); Short Strokes (Cycle World, 1977-1979); Hard Tale (Choppers, 1978-1979) plus The Adventures of Rickie Racer, and cooking strip (!) The Puttin Gourmet… America’s Favorite Low-Life Epicurean in Biker Lifestyle and FTW News. Four years later, the cartoonist unsuccessfully pitched a domestic (AKA “family”) strip called Ozone to LGBTQA news periodical The Advocate. Among its proposed quotidian cast were literal and metaphorical straight man Rodger and openly gay Leonard Goldman… who had a “roommate” named Larry Evans…

Gay Comix was an irregularly published anthology, edited at that time by Underground star Robert Triptow (Strip AIDs U.S.A.; Class Photo). He advised Barela to ditch the restrictive newspaper strip format in favour of longer complete episodes, and printed the first of these in Gay Comix #5 in 1984. The remodelled new feature was a huge success, included in many successive issues and became the solo star of Gay Comix Special #1 in 1992.

Leonard & Larry also showed up in prestigious benefit comic Strip AIDs U.S.A. before triumphantly relocating to The Advocate in 1988, and – from 1990 – to its rival publication Frontiers. The lads even moved into live drama in 1994: adapted by Theatre Rhinoceros of San Francisco as part of stage show Out of the Inkwell. In the 1990s their episodic exploits were gathered in a quartet of wonderfully oversized (220 x 280 mm) monochrome albums which gained a modicum of international stardom and some glittering prizes. This third compendium compiled by Palliard Press between 1996 -2000, follows Domesticity Isn’t Pretty and Kurt Cobain & Mozart Are Both Dead, whilst paving the way for last volume (to date) How Real Men Do It.

As previously stated, as well as featuring a multi-generational cast, Leonard & Larry is a strip that progressed in real time, with characters all aging and developing accordingly. The strips are not and never have been about sex – except in that the subject is a constant generator of hilarious jokes and outrageously embarrassing situations. Triumphantly skewering hypocrisy and rebuking ignorance with dry wit and superb drawing, episodes cover various couples’ home and work lives, constant parties, physical deterioration, social gaffes, rows, family revelations, holidays and even events like earthquakes and fanciful prognostications.

Following an Introduction from Animation historian Charles Solomon and Lief Wauters potted history of the strip ‘The Life and Times of Leonard & Larry’, a ‘Leonard & Larry Timeline’ provides a crucial curated recap in copious detail, including reintroducing the vast Byzantine, deftly interwoven cast, with past highlights and low points and reminds readers that this strip passes in real time and the players are aging just like we are…

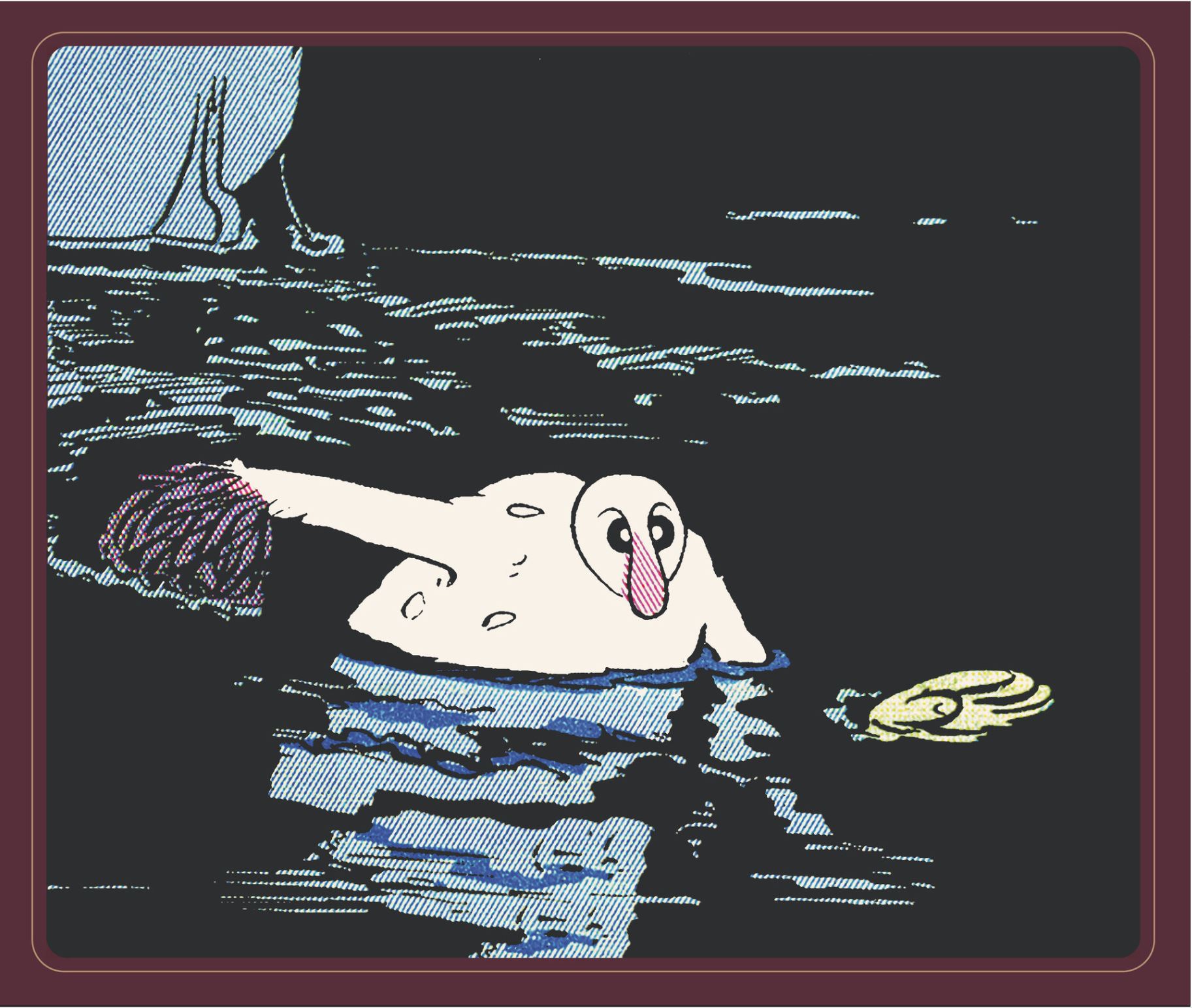

Star couple Leonard Goldman and Larry Evans live together despite vast family circles and friend groups all apparently at odds with each other. The feature also prominently and increasing plays with fantasy as dream manifestations – or are they actual ghosts? – of composers Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky and his bitter frenemy Johannes Brahms plague cast members: acting as a vanguard for even odder occurrences to come…

This family saga is primarily a comedy of manners, played out against social prejudices and grudging gradual popular acceptances, but it also has shocking moments of drama and tension and whole bunches of heartwarming sentiment set in and around West Hollywood.

The extensive Leonard & Larry clan comprise the former’s formidable unaccepting mother Esther – who still ambushes him with blind dates and nice Jewish girls – and the latter’s ex-wife Sharon and the sons of their 18-yeat marriage Richard and David. Teenaged Richard recently knocked up and wed equally school-aged Debbie, making the scrappy couple unwilling grandparents years (decades even!) before they were ready. The oldsters adore baby Lauren but didn’t need to relive all that aging trauma when Debbie announced there would soon be an older sister…

Maternal grandparents Phil and Barbra Dunbarton are ultra conservative and stridently Christian, spending a lot of time fretting over Debbie and Lauren’s souls and their own social standing. They’re particularly concerned over role models and what horrors she and her brother Michael are being exposed to whenever the gay guys babysit. Their appearances are always some of funniest and most satisfying as the deviant clan expands exponentially in this volume…

David Evans is as Queer as his dad, and works in Larry’s leather/fetish boutique store on Melrose Avenue. That iconic venue provides loads of quick, easy laughs and many edgy moments thanks to local developer/predatory expansionist Lillian Lynch who still wants the store at any cost. It’s also the meeting point for many other couples in Leonard & Larry’s eccentric orbit. Their friends/clients enjoy greater roles this time, offering other perspectives on LA life.

Flamboyant former aerospace engineer Frank Freeman lives with acclaimed concert pianist Bob Mendez and is saddled with an compulsive yen for uniforms. It comes in handy again when Bob’s sex-crazed celebrity stalker Fiona Birkenstock breaks jail to re-kidnap him – at least until she switches affection to a certain celebrity judge sentencing her…

Larry’s other employee is Jim Buchanan whose alarming dating history stabilised when he met a genuine cowboy at one of L & L’s parties. Merle Oberon was a newly “out” Texan trucker who added romance and stability to Jim’s lonely life. Sadly, it got complicated in other ways once Merle became a Hollywood soap star and his agents, managers and co-star convinced him his career needed Oberon back in that closet…

Jim, by the way, is the original and central focus of the overly-critical dead composers’ puckish visits…

Also catching attention this time are heated discussions on the supernatural as the ghost composers graduate from dream-based plot device to active participants, playing pranks on many more of the minor cast members. Their games re balanced with ever-kvetching aging-averse Larry painfully adapting to being a doting grandad/perennial babysitter. Jim and Merle meanwhile engage a psychic to exorcise their haunt housemates, blithely unaware that she’s an undercover tabloid hack looking for a juicy exposé…

Younger players take centre stage, offering the author opportunity to spike not just anti-gay bigots but take on good old-fashioned racism too, even delivering a gleefully potent poke at American fundamentalism when the “Christian Coalition” relentlessly pursues good old white, Texan celebrity Merle to be the face of their next “decency campaign” and just won’t take no for an answer…

A surprisingly hard-hitting – if deviously velvet-gloved – storyline sees Jim discovering he was adopted: in fact the child of an unwed catholic girl exploited by the Irish Church’s baby-selling scandal (you really should look up Ireland’s Mother & Baby Homes). Reeling and despondent, his downward spiral is resolved by Merle who secretly arranges a trip to Ireland and a family reunion no-one wanted but everyone benefitted from…

David is Larry’s gay son and not expected to cause chaos and consternation, but that ends when he and his bestie Collin help their lesbian roommate Nat get pregnant and our freaked out oldster contemplates becoming a grandfather yet again…

That hilariously potent arc is compounded when ex-wife Sharon attends one of their frequent dinner parties and gets off with the still-sore former spouse’s only straight acquaintance (classical violinist Gene Slatkin). The liaison sparks incomprehensible jealousy and primeval macho ownership behaviour in Larry, but it’s so much worse when he learns the result is geriatric pregnancy and his becoming an unpaid baby sitter for another family addition…

Extended saga ‘The Baby Shower’ finds the entire conflicted and in many parts intolerant extended family in one room and scoring points As first Sharon and then Nat go into labour it sparks fourth wall shenanigans as Larry again has a meltdown and flees from the hospital, archenemy Mike the midwife, all semblance of parental responsibility and general biological “ickiness”.

The feature provides plenty of moments of wild abandon too, such as when Larry loses a friend’s beloved dog and finds an enormous python with a very full stomach, fun with tarantulas and a startling dream sequence wherein grandkids (7-year-old Lauren and 3-year-old Michael) take over “creating” strip a few times, ultimately confirming grampy’s crazed conviction that he’s nothing but a character in a comic strip crafted by a sadist. Further hallucinogenic riffs – including cowboy antics and a rebellion of Barbie dolls – leads finally to a major emotional growth spurt and Larry’s return to the hospital just in time to join the happy events…

Leonard & Larry is a traditionally domestic marital sitcom/soap opera with Lucille Ball & Desi Arnaz – or more aptly, Dick Van Dyke & Mary Tyler Moore – replaced by a hulking bearded “bear” with biker, cowboy and leather fetishes and a stylishly moustachioed, no-nonsense fashion photographer. Taken in total, it’s a love story about growing old together, but not gracefully or with any dignity. Populated by adorable, appetising fully fleshed out characters, Leonard & Larry was always about finding and then being yourself and remains an irresistible slice of gentle whimsy to nourish the spirit and beguile the jaded. If you feel like taking a Walk on the Mild Side now this tome is still at large through internet vendors. So why don’t you?

Excerpts from the Ring Cycle in Royal Albert Hall © 2000 Palliard Press. All artwork and strips © 2000 Tim Barela. All rights reserved The Life and Times of Leonard & Larry © 2000 Lief Wauters.

After decades of waiting, the entire ensemble is available again courtesy of Rattling Good Yarns Press. Sublimely hefty hardback uber-compilation Finally! The Complete Leonard & Larry Collection was released in 2021, reprinting the entire saga – including rare as hens’ teats last book How Real Men Do It (978-1955826051). It’s a little smaller in page dimensions (216 x280mm) and far harder to lift, but it’s Out There if you want it…