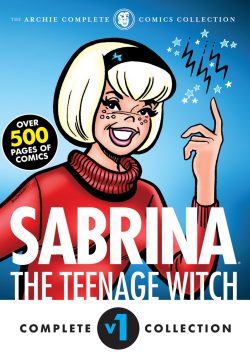

By George Gladir, Frank Doyle, Dick Malmgren, Al Hartley, Joe Edwards, Dan DeCarlo, Rudy Lapick, Vince DeCarlo, Bob White, Bill Kresse, Bill Vigoda, Mario Acquaviva, Jimmy DeCarlo, Chic Stone, Bill Yoshida, Stan Goldberg, Jon D’Agostino, Gus LeMoine, Harry Lucey, Marty Epp, Bob Bolling, Joe Sinnott & various (Archie Comic Publications)

ISBN: 978-1-936975-94-5

Sabrina the Teen-Age Witch debuted in Archie’s Mad House #22 (October 1962), created by George Gladir & Dan DeCarlo as a throwaway character in the gag anthology which was simply one more venue for comics’ undisputed kings of kids comedy. She soon proved popular enough to become a regular in the burgeoning cast surrounding the core stars Archie Andrews, Betty Cooper, Veronica Lodge and Jughead Jones.

By 1969 the comely enchantress had grown popular enough to win her own animated Filmation TV series (just like Archie and Josie and the Pussycats) and graduated to a lead feature in Archie’s TV Laugh Out before finally winning her own title in 1971.

The first volume ran 77 issues from 1971 to 1983 and, when a hugely successful live action TV series launched in 1996, an adapted comicbook iteration followed in 1997. That version folded in 1999 after a further 32 issues.

Volume 3 – simply entitled Sabrina – was based on new TV show Sabrina the Animated Series. This ran for 37 issues from 2000 to 2002 before a back-to-basics reboot saw the comicbook revert to Sabrina the Teenage Witch with #38, carefully blending elements of all the previous print and TV versions.

A creature of seemingly infinite variation and variety, the mystic maid continued in this vein until 2004 and issue #57 wherein, acting on the global popularity of Japanese comics, the company boldly switched format and transformed the series into a manga-style high school comedy-romance in the classic ShÅjo manner.

A more recent version abandoned whimsy altogether and depicted Sabrina as a vile and seductive force of evil (see Chilling Adventures of Sabrina)

This no-frills massively monochrome trade paperback (or digital download) gathers and represents all her appearances – even cameos on the covers of other Archie titles – from that crucial first decade and kicks off with an informative and educational Introduction courtesy of Editor-in-Chief Victor Gorelick before chronologically unleashing the wonderment in a year-by-year cavalcade of magic mystery and mirth.

Clearly referencing Kim Novak as seen in the movie Bell, Book and Candle, ‘Presenting Sabrina the Teenage Witch’ (by George Gladir, Dan DeCarlo, Rudy Lapick & Vince DeCarlo from Archie’s Mad House #22) debuted a sultry seductress with a wicked edge prankishly preying on mortals at the behest of Head Witch Della, whilst secretly hankering for the plebeian joys of dating…

Leading off the next year’s chapter, the creative team reunited for Archie’s Mad House #24 (February 1963), with ‘Monster Section’ depicting Sabrina bewitching boys the way mortal girls always have, whilst ‘Witch Pitch’ sees the young beguiler ordered to ensorcel the High School hockey team… with mixed results…

Archie’s Mad House #25 (April) focuses on the supernatural clan’s mission to destroy human romances. In ‘Sister Sorceress’ Della orders Sabrina to split up dating duo Hal and Wanda – with catastrophic results – before ‘Jinx Minx’ (AMH #26, June) finds Sabrina going too far with a love potion at a school dance…

Bob White’s Archie’s Mad House #27 cover (August 1963) leads into #28’s ‘Tennis Menace’ (inked by Marty Epp) with Sabrina’s attempts to enrapture a rich lad going infuriatingly awry. AMH #30 (December) offers pin-up ‘Teen-Age Section’ drawn by Joe Edwards, with Sabrina comparing historical ways of charming boys with modern mortal methods…

The 1964 material opens with a love potion pin-up ‘Teen Section’ by Edwards (from Archie’s Mad House #31, February) before Gladir & Edwards’ ‘Ronald the Rubber Boy Meets Sabrina the Witch Queen’ finds the magic miss disastrously swapping abilities with an elastic-boned pal.

Issue #36 (October, by Edwards) sees her failing to jinx her friends’ recreational evening in ‘Bowled Over’, after which (AMH #37, December) Gladir is reunited with Dan & Vince DeCarlo for a spot of ‘Double Trouble’ as gruesome Aunt Hilda tries to fix Sabrina’s appalling human countenance, only to become her unwilling twin…

In 1965 Sabrina’s only appearance was in a Harry Lucey-limned ad for Archie’s Mad House Annual, whereas the following year saw her triumphant return with illustrator Bill Kresse handling Gladir’s scripts for ‘Lulu of a Boo-Boo’ (Archie’s Mad House #45, February 1966). Here the witch-girl’s attempts to join the In Crowd constantly misfire whilst ‘Beach Party Smarty’ (#48, August) confirms this new trend as her spells to capture a hunky lad go badly wrong…

For ‘Go-Go Gaga’ (AMH #49, September) Gladir & Kresse pit the bonny bewitcher against a greedy entrepreneur planning to fleece school kids in his over-priced dance hall, whilst in #50 ‘Rival Reversal’ finds her failing to conjure a date and ‘Tragic Magic’ proves even sorcery can’t keep a teen’s room clean…

Art team Bill Vigoda & Mario Acquaviva join Gladir for 1967’s first tale. ‘London Lore’ (Archie’s Mad House #52, February) with Sabrina transporting new boyfriend Donald to the heart of the Swinging Scene but ill-equip him for debilitating culture-shock, after which ‘School Scamp’ (Gladir and Dan, Jimmy & Vince DeCarlo, from AMH #53, April) again proves magic has no place in human education…

In issue #55 Gladir, Dan DeCarlo & Lapick reveal how Sabrina’s wishing to help is a doubly dangerous proposition in ‘Speed Deed’ whilst in #58 (December and illustrated by Chic Stone & Bill Yoshida) the trend for ultra-skinny fashion models leads to a little shapeshifting in ‘Wile Style’…

1968 opens with Gladir, Stone & Yoshida exploring the down side of slot-car racing in ‘Teeny-Weeny Boppers’ (AMH #59, February) after which ‘Past Blast’ (#63, September by Gladir, Stan Goldberg, Jon D’Agostino & Yoshida) sees the mystic maid time-travel in search of Marie Antoinette, Pocahontas and Salem sorceress Hester.

The year wraps up with ‘Light Delight’ (Gladir, White, Acquaviva & Yoshida: Archie’s Mad House #65, December) as Sabrina’s aunts Hilda and Zelda try more modern modes of witchly transport…

With the advent of Sabrina on television, the end of 1969 saw a sudden leap in her comics appearances to capitalise on the exposure and resulted in a retitling of her home funnybook.

Again crafted by Gladir, White, Acquaviva & Yoshida, ‘Glower Power’ comes from Mad House Ma-Ad Jokes #70 (September) with Sabrina duelling another teen mage before the cover of Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #1 (December: rendered by Dick Malmgren & D’Agostino) leads into ‘Super Duper Party Pooper’ and the instant materialisation of a new sitcom lifestyle for the jinxing juvenile.

Sabrina yearns to be a typical High School girl. She lives in suburban seclusion with Hilda and Zelda and Uncle Ambrose. She has a pet cat – Salem – and is tentatively “seeing†childhood pal Harvey Kinkle. The cute but clueless boy reciprocates the affection but is far too scared to rock the boat by acting on his own desires.

He has no idea that his old chum is actually a supernatural being…

This opening sally depicts what happens when surly Hilda takes umbrage at the antics of Archie and his pals when they come over for a visit, whilst ‘Great Celestial Sparks’ (pencilled by Gus LeMoine) reveals what lengths witches go to when afflicted with hiccups…

A full-on goggle-box sensation, Sabrina blossomed in 1970, beginning with a little flying practice in ‘Broom Zoom’, boyfriend trouble in ‘Hex Vex’, fortune-telling foolishness in ‘Hard Card’, amulet antics in ‘Witch Pitch’, and kitchen conjurings in ‘Generation Gap’: all by Gladir, LeMoine, D’Agostino & Yoshida from Mad House Ma-Ad Jokes #72 (January).

The issue also offered sporting spoofs in ‘Bowl Roll’ (drawn by Dan DeCarlo).

The so-busy cover of Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #2 (March 1970) segues into Gladir, Dan D, Lapick & Yoshida’s ‘A Plug for The Band’ with Sabrina briefly joining The Archies’ pop group, whilst LeMoine contributes a brace of half-page gags ‘Sassy Lassy’ and ‘Food Mood’ and limns ‘That Ol’ Black Magic’ wherein the winsome witch’s gifts cause misery to all her new friends in Riverdale…

Dan DeCarlo & Lapick’s June cover for Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #3 leads into Malmgren-scripted ‘Double Date’ with hapless Harvey causing chaos at home until Ambrose finds a potential putrid paramour for Aunt Hilda.

Dan D & Lapick then launch an occasional series on stage magic in the first of many ‘Sabrina Tricks’ pages, before single-pagers ‘Goodbye Mr. Chips’, ‘The Hand Sandwich’, ‘The Sampler’, ‘Never on Sundae’ and ‘Finger Licken Good’ reveal a growing divide between house-proud Hilda and accident-prone, ever-ravenous Harvey.

Interspersed with three more ‘Sabrina Tricks’ pages, the mystic mayhem continues with mini-epic ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ (Malmgren, LeMoine, D’Agostino & Yoshida) as our witch girl disastrously attempts to make Jughead Jones more amenable to Big Ethel‘s romantic overtures.

Then the food fiascos resume with the LeMoine-limned ‘Good and Bad’ as Sabrina’s every good intention is accidentally twisted to bedevil her human pals

Taken from Mad House Glads #74 (August 1970), Gladir & LeMoine’s half-page chemistry gag ‘Strange Session’ is oddly balanced by the painterly ‘Blight Sight’ of long-forgotten never-was Bippy the Hippy, but we’re back on track and at the beach for Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #4 (September, Gladir, Vigoda, Lapick & Yoshida).

In ‘To Catch a Thief’ Sabrina again assists Ethel in pinning down the elusive and love-shy Jughead, and rounding out the issue are single page pranks ‘Beddy Bye Time’ (DeCarlo & Lapick), another ‘Sabrina Tricks’ lesson and seaside folly ‘In the Bag’ from LeMoine & D’Agostino.

ATVL-O #5 (November) then offers up Gladir, Vigoda & Stone’s ‘I’ll Bite’ as Sabrina’s hungry schoolfriends learn the perils of raiding Hilda’s fridge and Gladir, DeCarlo & Lapick’s ‘Hex Vex’ as Della storms in, demanding tardy Sabrina fulfil her monthly quota of bad deeds…

Sabrina is an atypical witch: living in the mundane world and assiduously passing herself off as normal and 1971 opens with DeCarlo & Lapick’s cover for Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #6 (February) and ‘Match Maker’ by Frank Doyle, Harry Lucey & Marty Epp as Hilda tries to get rid of Harvey by making him irresistible to Betty & Veronica. No way that can go wrong…

‘Sabrina the Teen-Age Witch’ (Gladir, LeMoine, D’Agostino & Yoshida) then uses her powers openly with some kids and learns a trick even ancient crone Hilda cannot fathom. Bolstered by a ‘Sabrina Tricks’ page, ‘Carry On, Aunt Hilda’ (Malmgren, LeMoine & Lapick) hilariously depicts lucky stars shielding Harvey from the wrath of irascible Aunt Hilda…

Bowing to popular demand, the eldritch ingenue finally starred in her own title from April 1971. Dan DeCarlo & Lapick’s cover for Sabrina the Teen-Age Witch #1 hinted at much mystic mirth and mayhem which began with ‘Strange Love’ (Doyle, Dan D & Lapick), revealing the star’s jealous response to seeing Harvey with another girl. This is supplemented by ‘Sabrina and Salem’s Catty Quiz’ before hippy warlock Sylvester comes out of the woodwork to upset Hilda’s sedate life in ‘Mission Impossible’ (Malmgren, LeMoine & D’Agostino).

Another ‘Sabrina Puzzle’ neatly moves us to Doyle, Dan D & Lapick’s ‘An Uncle’s Monkey’ with Harvey and a pet chimpanzee pushing Hilda to the limits of patience and sanity…

The cover of Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #7 (May) precedes a long yarn by Doyle, Bob Bolling & D’Agostino as ‘Archie’s TV Celebrities’ (the animated Archies, Sabrina and Josie and the Pussycats) star in ‘For the Birds’ with a proposed open-air concert threatened by the protests of a bunch of old ornithology buffs.

The celebrity pals then tackle an instrument-stealing saboteur in ‘Sounds Crazy to Me’ (Malmgren, LeMoine & D’Agostino), after which Sabrina cameos on the cover of Jughead #192 (May, by Dan DeCarlo & Lapick) before heading for the cover of her own second issue (DeCarlo & Lapick, July). Within those pages Malmgren scripts ‘No Strings Attached’ as the Archies visit their bewitching buddy just as Hilda turns hapless Harvey into an axe-strumming rock god…

‘Witch Way is That’ sees Hilda quickly regret opening her house to Tuned In, Turned On, Dropped Out Cousin Bert, after which Malmgren, Lucey & Epp show Archie suffering the jibes and jokes of ‘The Court Jester’ Reggie – until Sabrina adds a little something extra to the Andrews boys’ basketball repertoire..

At this time the world was undergoing a revival of supernatural interest and gothic romance was The Coming Thing.

In a rather bold experiment, Sabrina was given a shot at a dramatic turn with Doyle, Bolling, Joe Sinnott & Yoshida cooking up ‘Death Waits at Dumesburry’: a relatively straight horror mystery with Sabrina battling a sinister maniac in a haunted castle she had inherited…

Rendered by LeMoine & D’Agostino, the cover of Jughead’s Jokes #24 (July 1971) brings us back to comedy central, as does their cover for Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #8 (August) and Malmgren’s charity bazaar-set tale ‘A Sweet Tooth’, with the winsome witch discovering that even her magic cannot make Veronica’s baked goods edible…

Dan DeCarlo’s cover for ‘Sabrina the Teen-Age Witch #3 (September) foreshadows a return to drama but in modern milieu as ‘House Breakers’ (Malmgren, DeCarlo & Lapick) finds Harvey and Sabrina stranded in an old dark mansion with spooks in situ, after which ‘Spellbinder’ (Doyle, Al) sees Hilda cringe and curse when human catastrophe Big Moose pays Sabrina a visit.

Hartley & D’Agostino fly solo on ‘Auntie Climax’ as irresistibility spells fly and both Archie and Hilda are caught in an amorous crossfire before Malmgren, Bolling & Lapick show our cast’s human side as Archie, Jughead and Sabrina intervene to help a juvenile thief caught in a poverty trap in ‘The Tooth Fairy’…

A trio of DeCarlo & Lapick covers – Archie’s TV Laugh Out #9 (September), Archie’s Pals ‘n’ Gals #66 (October) and Sabrina the Teen-Age Witch #4 (October) lead into the teen thaumaturge’s fourth solo comicbook, where Doyle, Goldberg & D’Agostino set the cauldron bubbling with ‘Hex Marks the Spot’ as Aunts Hilda and Zelda nostalgically opine for their adventurous bad old days but something seems set on thwarting every spell they cast, after which ‘Which Witch is Right?’ (pencilled by LeMoine) finds obnoxious Reggie Mantle uncovering Sabrina’s sorcerous secrets.

Goldberg & Sinnott illustrate ‘Switch Witch’ as officious Della suspends Sabrina’s powers as a punishment and can’t understand why the girl is delirious instead of heartbroken whilst Hartley & Sinnott contribute a run of madcap one-pagers by Gladir & Malmgren Doyle with clue-packed titles such as ‘Out of Sight’, ‘Beauty and the Beast’, ‘The Teen Scene‘, ‘So That’s Why’ and ‘Time to Retire’.

Wrapping up the issue is ‘The Storming of Casket Island’ by Doyle, LeMoine & D’Agostino, blending stormy sailing with sinister swindling skulduggery and menacing mystic retribution…

More covers follow: Archie #213 and Archie’s TV Laugh Out #10 (both November and by Dan DeCarlo & Lapick) and Archie’s Christmas Stocking #190 (Hartley & D’Agostino, December) which latter also contributes Hartley & Sinnott’s ‘Card Shark’, with Sabrina joining Archie and the gang to explore the point and purpose of seasonal greetings postings before DeCarlo & Lapick’s cover of Betty and Me #39 brings the momentous year to a close…

The last year covered in this titanic tome is 1972 and kicks off with DeCarlo & Lapick’s cover for Archie Annual #23, before their Sabrina’s Christmas Magic #196 cover (January) opens the book on a winter wonderland of seasonal sentiment. It all starts with ‘Hidden Claus’ (by featured team Hartley & Sinnott) as Sabrina ignores her aunt’s mockery and seeks out the real Father Christmas – just in time to help him with an existential and labour crisis…

‘Sabrina’s Wrap Session’ offers tips on gifting and packaging whilst ‘Hot Dog with Relish’ sees the witch woman zap Jughead’s mooching canine companion and make him a guy any girl could fall for.

Then Doyle, Goldberg & Sinnott concoct ‘The Spell of the Season’, depicting our troubled teen torn between embracing Christmas and wrecking it as any true witch should. Guess which side wins the emotional tug-of-war?

More handicraft secrets are shared in ‘Sabrina’s Instant Christmas Decorations’ before Hartley & Sinnott craft ‘Sabrina Asks… What Does Christmas Mean to You?’ and ‘Sabrina Answers Questions About Christmas’, after which cartoon storytelling resumes with ‘Mission Possible’ as Hilda and Zelda find their own inner Samaritans.

Despite a rather distressing (and misleading) title ‘Popcorn Poopsie’ reveals way of making tasty decorative snacks whilst ‘Sabrina’s Animal Crackers’ tells a tale of men turned to beasts before a yuletide ‘Sabrina Pin-Up’ and exercise feature ‘Sabrina Keeps in Christmas Trim’ returns us to the entertainment section.

An all Hartley affair, ‘Sabrina’s Witch Wisher’ examines what the vast cast would say if given one wish, after which Doyle, Goldberg & Sinnott conclude this mammoth meander down memory lane by revealing how an evil warlock was punished by becoming ‘A Tree Named Obadiah’. Now – decked out in lights and tinsel – he’s back and making mischief in Veronica’s house…

An epic, enticing and always enchanting experience, the classic adventures of Sabrina the Teenage Witch are sheer timeless comics delight that no true fan will ever grow out of…

© 1962-1972, 2017 Archie Comic Publications, Inc. All rights reserved.