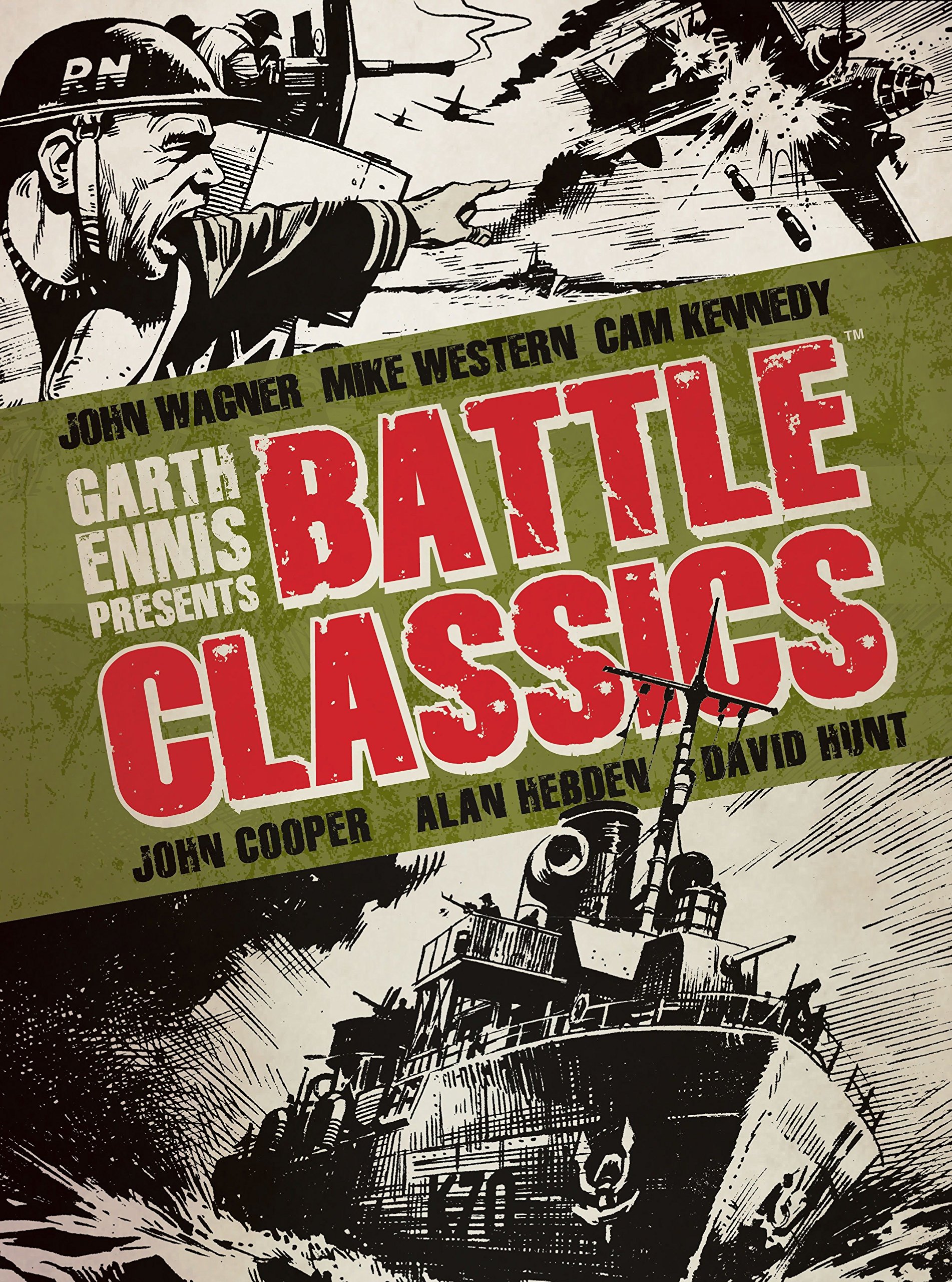

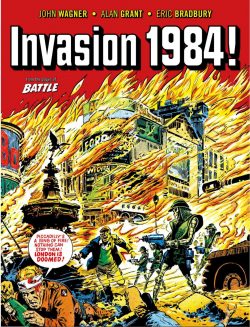

By John Wagner, Alan Grant, Eric Bradbury & various (Rebellion Studios)

ISBN: 9-781-78108-675-9 (TPB/Digital edition)

For most of the industry’s history, British comics were renowned for the ability to tell a big story in satisfying little instalments. This, coupled with supremely gifted creators and the anthological nature of our publications, guaranteed hundreds of memorable characters and series seared themselves into the little boy’s psyche lurking inside most adult males.

One of the last great weeklies was Battle: a strictly combat-themed confection which began as Battle Picture Weekly, launching on 8th March 1975. Through absorption, merger and re-branding (as Battle Picture Weekly & Valiant, Battle Action, Battle, Battle Action Force and Battle Storm Force), it reigned supreme in Blighty before itself being combined with Eagle on January 23rd 1988.

Over 673 blood-soaked, testosterone-drenched issues, it carved its way into the bloodthirsty hearts of a generation, producing some of the best and most influential war stories ever.

Happily, many of the very best – like Charley’s War, The Sarge and El Mestizo – have been preserved and revisited in resilient reprint collections, but there’s still loads of superb stuff to rediscover, as typified by recent releases from Rebellion Studios (stay alert for those in days to come, chums…!).

This is nothing like any of them…

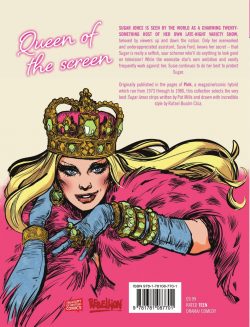

This particular combat compendium re-presents possibly the most unconventional series in the title’s eccentric history one that ran in Battle from 26th March to 31st December 1983. The entire saga is done in one book and comes with an enthused Introduction from editor and veteran scripter (Death Wish, Survivor, Real Roy of the Rovers Stuff, Comic Book Hero) Barrie Tomlinson.

What we have in Invasion 1984! is a classic end of the world/alien attack yarn in the vein of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, published in the months leading up to the long-awaited literary moment of prophesied dystopia foretold by George Orwell. Deep stuff for a kids’ comic primarily about how their grandads were shot at by German and Japanese soldiers. However, the topic was evergreen, the fantastic elements were commonplace at this time and the actual work was left to three of the industry’s biggest guns…

Credited writer “R. Clark” was in fact John Wagner working with his regular co-scripter Alan Grant. Wagner (Bella at the Bar, One-Eyed Jack, Joe Two Beans, Roy of the Rovers, Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog, Outcasts, Fight for the Falklands, Button-Man, The Bogie Man, Batman, A History of Violence, Darkie’s Mob, Rok of the Reds and countless more) was born in Pennsylvania in 1949, but returned to Greenock in Scotland with his war-bride mum and siblings 12 years later.

He began his professional comic career at the end of the 1960s, firstly in an editorial capacity with Dundee-based DC Thomson & Co. He became a freelance writer soon after and moved to IPC in London. With him came colleague Alan Grant…

Born in Bristol, Grant (February 9th 1949 – July 21st 2022) grew up a true Scot in the heart of Midlothian. Wayward and anarchic, after trying regular life a couple of times he began his comics career in 1967 as an editor for DC. Soon he was writing scripts – many with Wagner – and inventing characters, first for British outfits but eventually all over the world.

His triumphs include Tarzan, Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog, Batman, Lobo, L.E.G.I.O.N., Judge Anderson, The Bogie Man, Channel Evil, Kidnapped, The Demon, Robo-Hunter, Anarky, The Loxleys and the War of 1812, Rok of the Reds and so many more.

He also contributed to amateur fanzines, encouraging and supporting new talent; adapted classic literature to comics form for major art festivals; worked in animation; organized his own comic conventions (in home village Moniaive) and self-published and ran his own publishing house Berserker Comics. In 2020, he led a community outreach project to inform about CoVID-19 via a comic book.

Handling the art was arguably Britain’s most accomplished dramatic illustrator.

The incredible and prolific career of Eric Bradbury (January 4th – 1921 – May 2001) began in 1949 in Knockout. Born in Sydenham, Kent, he studied at Beckenham Art School from 1936 and served in the RAF as a bomber rear gunner during the war. Demobbed, he worked at Gaumont-British Animation, where he met other future cartooning and comics masters Mike Western, Ron Smith, Bill Holroyd, Harry Hargreaves and Nobby (AKA Ron) Clark. When the studio closed Clark and Bradbury were hired by comics everyman Leonard Matthews at Amalgamated Press (latterly Fleetway/IPC).

Frequently working with studio mate Western, Bradbury drew strips such as Our Ernie, Blossom, Lucky Logan, Buffalo Bill, No Hiding Place, The Black Crow and Biggles. He was an “in-demand” illustrator well into the 1990s on many landmark strips including The Avenger, Cursitor Doom, Phantom Force 5, Maxwell Hawke, Joe Two Beans, Mytek the Mighty, Death Squad, Doomlord, Darkie’s Mob, Crazy Keller, Hook Jaw, The Sarge, Invasion (the 2000 AD strip), The Mean Arena, The Fists of Jimmy Chang, The Dracula Files, Rogue Trooper, Future Shocks, Tharg the Mighty and so much more…

Together this triumphant triumvirate crafted a sublimely simple but compellingly cathartic scary story of doom and resurrection, which began and proceeded in real time one year into the future…

On March 21st 1984, astronomers detect a vast fleet of city-sized extraterrestrial craft heading directly for Earth. When space shuttle Columbia is despatched to intercept and extend peaceful greetings, it is blasted to atoms…

From then on, the 3-page weekly instalments catalogue the crushing of our planetary defences, military helplessness, mass panic and displacement of humanity. Terrified and running, people are picked off by silent skeletal warriors or bombed and ray-blasted into annihilation. Once the city-ships land, increasing numbers of shattered shell-shocked humans are captured and flown away…

Amongst the panicking masses fleeing London is language professor Edward Lomax who quite sensibly packs up his wife Marion and son Mike and tries desperately to get out of the capital. As Britain’s armed forces stubbornly resist to the last, the Lomaxes strive to escape the carnage and Edward confirms his own fighting spirit by killing dozens of the intruders with their own weapons.

Ultimately, resistance proves useless and civilisation falls in days, but just when Edward is ready to give up, he and his loved ones are somehow found and rescued by an unconventional unit of brutal killers…

Modern day Dirty Dozen Storm Squad have been tasked with finding the professor by the last free remnants of the army. Plucked from the rubble of London after days of constant running and killing, Lomax and his kin are whisked to a hidden Command Bunker in Bedfordshire, where General Lapsley and Britain’s Defence Secretary (the last survivor of Parliament) put him to work finding out how the invaders communicate and devising a way to talk to them…

The task becomes increasingly urgent after even nuking occupied cities fails to slow the invaders, and Storm Squad (Major “Mad Mac” McVicker, Sergeant Dent, Corporal Cheyney, Plank, creepy Geiger, repulsive deviant Burke and the rest) are despatched to capture some live “spooks” to experiment on…

The most savagely effective killers on Earth quickly succeed – despite sustained resistance from the aliens and opportunistic interference from humans quickly returned to primal self-reliance. With the world a depleted wreck mired in constant conflict, Lomax cracks the mystery, just as Storm Squad learn first-hand what’s become of the millions taken by the Spooks. It only makes more imperative his efforts to talk to the newcomers…

His inevitable success comes at a cost and illuminate a relentless countdown. The aliens have brought a ghastly plague into the bunker that is also ravaging what remains of life on Earth…

At last aware of why they’re here and determined to secure the spooks’ universal cure for illness, Earth’s last defenders deploy for their final sortie with an ultimate weapon of their own, knowing they won’t all be standing at the end…

Bombastic, brilliantly bellicose and mischievously misusing the British Bulldog Spirit, this grim game-changing fable is a delightful response to the toxic tone of the mid-Eighties, whilst still fabulously filling the brief of a boys’ combat yarn: offering casual heroism and vicarious carnage sans any moral nuance. It’s a case of us or them and we will always choose us…

This mostly monochrome masterpiece also includes the 5 full-colour covers the short series spawned plus biographies of all involved, offering the kind of uncomplicated unshaded thrills we all secretly yearn for…

© 1983, 2019 Rebellion Publishing Ltd. All Rights Reserved.