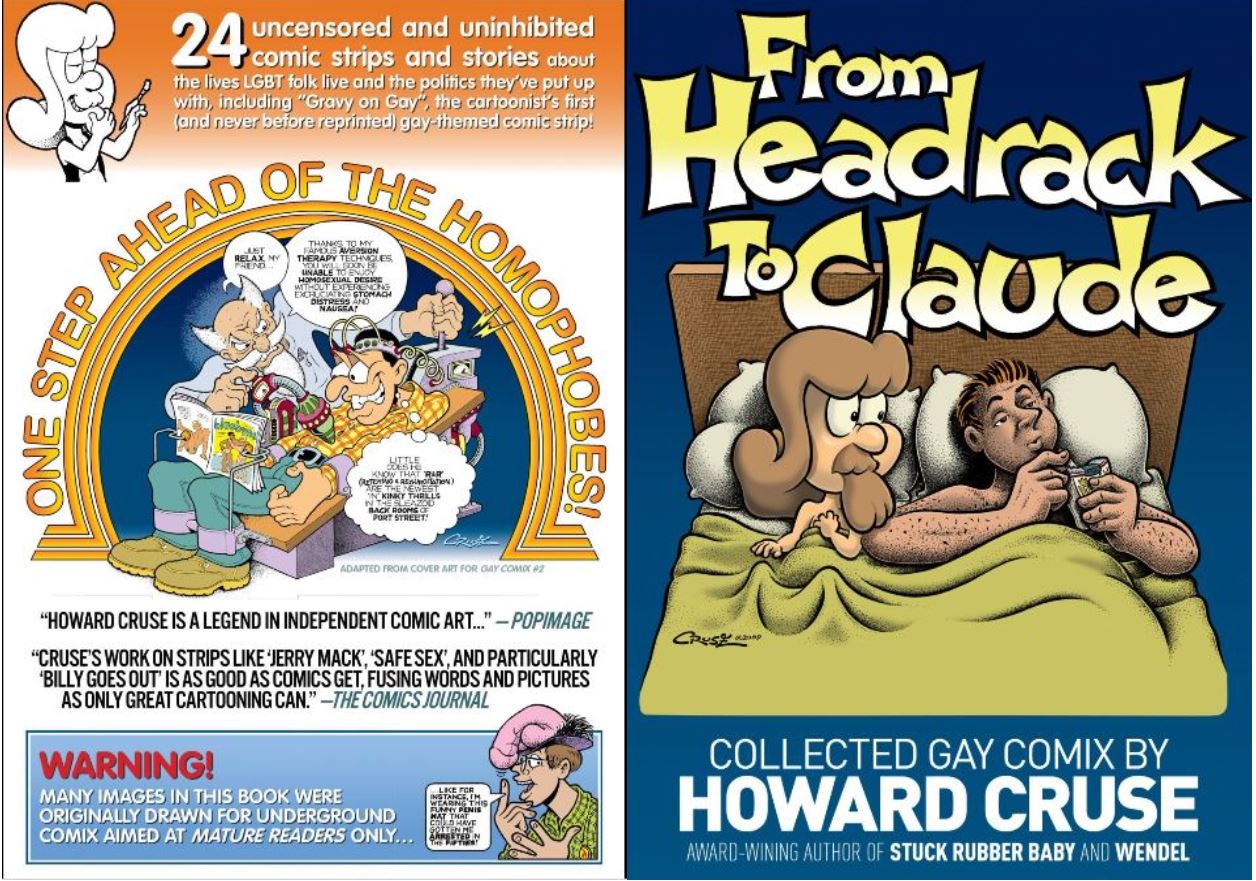

By Howard Cruse (Nifty Kitsch Press/Northwest Press)

ISBN: 978-0-578-03251-1 (TPB/Digital edition)

It’s long been an aphorism – if not an outright cliché – that Gay comics – can we be contemporary and say LGBTQIA+? – have long been the only place in the graphic narrative business to see real romance in all its joy, pain, glee and glory.

It’s still true: an artefact, I suppose, of a society seemingly obsessed with demarcating and separating sex and love as two utterly different and possibly even opposing principles and activities. I’d like to think that here in the 21st century – at least in the more sensible, civilised parts of it – we’ve outgrown the juvenile, judgemental, bad old days and can simply appreciate powerfully moving and/or funny comics about people of all sorts without any kind of preconception.

Sadly, that battle’s nowhere near won yet and in truth it all looks pretty bleak unless you’re a fundamentalist zealot or bigot. Hopefully, compendia such as this will aid the fight, if only we can get the other side to read them…

To facilitate that, after this archive was originally self-published in 2008 it was rendered fully digital – with updates and extra material – from those wonderful people at Northwest Press. Oh, and there’s an abundance of sex and swearing on view, so if you’re the kind of person liable to be upset by words and pictures of an adult nature (such as joyous, loving fornication between two people separated by age, wealth, social position and race who happily possess and constantly employ the same range of naughty bits on each other) or sly mockery of deeply-held, outmoded and ludicrous beliefs then best retreat and read something else.

In fact, just go away: you have no romance in your soul or love in your heart.

Howard Cruse (May 2nd 1944-November 26th 2019) enjoyed a remarkable cartooning career spanning decades that overlapped a number of key moments in American history and social advancement. Beginning as a hippy-trippy, counter-culture, Underground Comix star with beautifully drawn, witty, funny (not always the same thing in those days – or now, come to think of it) strips, his work evolved over years into a powerful voice for change in both sexual and race politics. Initially as strips in magazines but ultimately through such superb collections and Original Graphic Novels as Wendel and Stuck Rubber Baby: an examination of oppression, tolerance and freedoms in 1950s America.

Since then he has become a columnist, worked on other writers’ work, illustrated an adaptation of Jeanne E. Shaffer’s The Swimmer With a Rope In His Teeth and continued his own unique brand of cartoon commentary.

Born the son of a Baptist Minister in Birmingham, Alabama, Cruse grew up amid the instinctive race-based privilege and smouldering intolerance of the region’s segregationist regime: an atmosphere that shaped him on a primal level. In the late ‘60s, he escaped to Birmingham-Southern College to study Drama: graduating and winning a Shubert Playwriting Fellowship to Penn State University.

Campus life never really suited him and he dropped out in 1969. Returning to the South, he joined a loose crowd of fellow Birmingham Bohemians; allowing room to blossom as a creator. By 1971, Cruse was drawing a spectacular procession of strips for an increasingly hungry and growing crowd of eager admirers. Whilst working for a local TV station as both designer and children’s show performer, he created a kid’s newspaper strip about talking squirrels Tops & Button, and still found time to craft the utterly whimsical and bizarre tales of a romantic quadrangle. Intended for the more discerning college crowd he remained in contact with, these strips appeared in a variety of college newspapers and periodicals and starred a very nice young man and his troublesome friends…

In 1972 the strip was “discovered” by publishing impresario Denis Kitchen who began disseminating Barefootz to a far broader audience via such Underground periodical publications as Snarf, Bizarre Sex, Dope Comix and Commies From Mars: all published by his much-missed Kitchen Sink Enterprises.

Kitchen also hired Cruse to work on an ambitious co-production with rising powerhouse Marvel Comics: attempting to bring a (somewhat sanitised) version of the counter-culture’s cartoon stars and sensibilities to the mainstream. The Comix Book was a traditionally packaged and distributed newsstand magazine that only ran to a half-dozen issues. Although deemed a failure, it provided the notionally more wholesome and genteel Barefootz with a larger audience and yet more avid fans…

As well as being an actor, designer, art-director and teacher, Cruse appeared in Playboy, The Village Voice, Heavy Metal, Artforum International, The Advocate and Starlog and countless other publications, yet the tireless story-man found the time and resources to self-publish Barefootz Funnies: two comic collections of his addictively whimsical strip in 1973.

For us, a captivatingly forthright grab-bag and memoir gathers the snippets and classics left out of previous must-have collections The Compete Wendel and Early Barefootz, with Cruse tracing his development through cartoons and strips all thoroughly and engagingly annotated and contextualised by the author himself: fondly, candidly revisited against a backdrop of the men he loved at the time.

Acting as an historical place-setter, Cruse’s informative Preface sets the ball rolling, laconically tracing his artistic career and development through domestic autobiographical strip ‘Communique’ (from Heavy Metal) to unveil home life at the time. A more detailed exploration overview of the Queer comics scene follows in ‘From Miss Thing to Jane’s World’ before the book truly begins.

For a better, fuller understanding you’ll really want to see the aforementioned Wendell and Barefootz collections, but for now we relive history in first chapter Artefacts & Benchmarks Part 1: 1969-76, blending contextualising prose recollection with noteworthy strip ‘That Night at the Stonewall’s’, advertising art, abortive newspaper strip sample, an episode of Tops & Button, and other published work, plus gay sitcom feature ‘Cork & Dork’.

An early example of advocacy comes from wry cartoon homily ‘The Passer-By’ before further reminiscences and picture extracts take us to an uncharacteristically strident and harsh breakthrough.

Preceded by explanatory sidebar ‘Backstory: Gravy on Gay’, we are formally introduced to Barefootz’s, way-out friend confidante – and openly gay hippy rebel – Headrack in ‘Gravy on Gay’: wherein – the laid-back easy-going artist is confronted with the ugly, mouthy side of modern living as voiced by obnoxious jock jerk Mort…

The march of progress continues in Artefacts & Benchmarks Part 2: 1976-80, detailing a variety of comics jobs from Dope Comix and Snarf to the semi-legitimacy of Playboy and Starlog. It also features the first meeting with life partner – and ultimately, husband – Eddie Sedarbaum before My Strips from Gay Comix 1980-90 traces his editorial career on the landmark anthology through reprints of his own strip contributions.

It begins in ‘Billy Goes Out’: recalling the joyous – or it that empty and tedious? – hedonistic freedoms of the days immediately before the AIDS crisis…

Incisive cloaked autobiographical fable ‘Jerry Mack’ takes us inside the turbulent mind of an ultra-closeted church minister in full regretful denial, after which further heartbreak is called up in devious tragedy ‘I Always Cry at Movies’ before home chores are dealt with in a manly manner in ‘Getting Domestic’.

Historical and political insight comes in ‘Backstory: Dirty Old Lovers’ before the outrageous and hilarious antics of the oldest lovers in town scandalise the Gay community in ‘Dirty Old Lovers’, whilst the thinking behind clarion call ‘Safe Sex’ is detailed in a ‘Backstory’ article prior to a straightforward examination of Acquired Immune-Deficiency Syndrome and its effects on personal health and public consciousness…

Surreal comedy infuses the tale of a man’s man and his adored ‘Cabbage Patch Clone’ after which faux ad ‘I Was Trapped Naked inside the Jockey Shorts of the Amazing Colossal Man!’ and Matt Groening spoof ‘Gay Dorks in Fezzes’ closes this chapter to make way for Topical Strips 1983-93.

With Cruse’s particular brand of “Gay” commentary/advocacy reaching more mainstream audiences through publications like The Village Voice, a ‘Backstory’ relates the author’s ultimately unnecessary anxiety over inviting in the wider world through polemical sally ‘Sometimes I Get So Mad’ and wickedly pointed social and media satire ‘The Gay in the Street’. That oracular swipe and ‘1986 – An Interim Epilogue’ are also deconstructed by Backstory segments (the latter being a 2-page addendum created for the Australian release of ‘Safe Sex’ in Art & Text magazine) before ‘Backstory: Penceworth’ shares one of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s vilest moments.

In 1988, her government attempted to set back sexual freedom to the Stone Age (or Russia, Turkey, Nigeria and other uncivilised countries today) by prohibiting the “promotion of homosexuality”. The British law – (un)popularly known as Clause 28 – was resisted on many fronts, including benefit comic AARGH (Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia). Invited to contribute, Cruse channelled Hillaire Belloc’s Cautionary Verses and excoriatingly assaulted the New Nazism with ‘Penceworth’: a charming illustrated poem like a spiked cosh snuggled inside a rainbow coloured velvet slipper…

Luxuriating in righteous indignation and taking his lead from the New York Catholic Church’s militant stance against the LGBT community, Cruse then illuminated a supposed conference between ‘The Kardinal & the Klansman in Manning the Phone Bank’ and targeted similar anti-gay codicils in America’s National Endowment for the Arts in ‘Homoeroticism Blues’…

Another Backstory explains how and why a scurrilous article in Cosmopolitan resulted in ‘The Woeful World of Winnie and Walt’ – a complacency-shattering tale in Strip AIDS USA, pointedly reminding White Heterosexuals that the medical horror wasn’t as discriminating as they would like to believe…

That theme is revisited with the kid gloves off in ‘His Closet’, after which ‘Backstory: Rainbow Curriculum Comix’ clarify how School Board rabble-rouser Mary Cummings set back decades of progress in American diversity education through her oratorical witch hunts. Cruse’s potent responses ‘Rainbow Curriculum Comix’ and ‘The Educator’ follow…

The artist’s Late Entries 2000-08 round off the historical hay ride: snippets including a full-colour rebuttal from Village Voice to Dr. Bruce Bagemihl’s study on animal homosexuality. ‘A Zoo of Our Own’ is accompanied by a fulsome Backstory and followed by wryly engaging modern fable ‘My Hypnotist’ and semi-autobiographical conundrum ‘Then There Was Claude’ before the bemused wonderment wraps up with prose article ‘I Must Be Important …Cause I’m in a Documentary (2011)’ and a superb Batman pin-up/put down…

This is a sublime and timeless compilation: smart, funny, angry when needful and always astonishingly entertaining. Read it with Pride.

© 1976-2008 Howard Cruse. All rights reserved.

For further information and great stuff check out Howardcruse.com