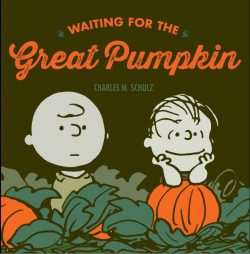

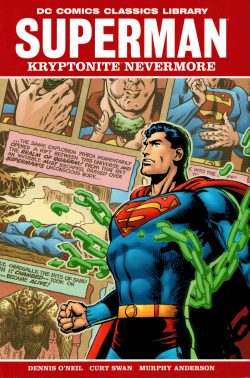

By Dennis O’Neil, Curt Swan, Murphy Anderson, Dick Giordano & various (DC Comics)

ISBN: 978-1-4012-2085-3 (HB)

While looking through old collections in my morbid response to the death of Denny O’Neil, I happened up on this book again. It’s the epitome of a comics classic and still a true joy to read. Why is it and so many other brilliant tomes like out of print and frustratingly unavailable in digital editions? I won’t stop asking, but rather than wait, why don’t you track this down now and give yourself a grand pre-Christmas treat?

Superman is the comic book crusader who started the whole genre and, in the decades since his debut in 1938, has probably undertaken every kind of adventure imaginable. With this in mind it’s tempting and very rewarding to gather up whole swathes of his inventory and periodically re-present them in specific themed collections, such as this hardback commemoration of one his greatest extended adventures. It was originally released just as comics fandom was becoming a powerful – if headless – lobbying force reshaping the industry to its own specialised desires.

When Julie Schwartz took over the editorial responsibilities of the Man of Steel in 1970, he was expected to shake things up with nothing less than spectacular results. To that end, he incorporated many key characters and events that were developing as part of fellow iconoclast Jack Kirby’s freshly unfolding “Fourth Worldâ€.

That bold experiment was a breathtaking tour de force of cosmic wonderment which introduced a staggering new universe to fans; instantly and permanently changing the way DC Comics were perceived and how the entire medium could be received.

Schwartz was simultaneously breathing fresh life into the powerful but moribund Superman franchise and his creative changes were just appearing in 1971. The new direction was also the vanguard and trigger for a wealth of controversial and socially-challenging material unheard of since the feature’s earliest days: a wave of tales described as “relevantâ€â€¦

Here the era and those changes are described and contextualised – after ‘A Word from the Publisher’ – in Paul Levitz’s Introduction, after which the first radical shift in Superman’s vast mythology begins to unfold.

With iconic covers by Neal Adams, Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson this titanic tome collects Superman #233-238 and #240-242, originally running from January to September 1971.

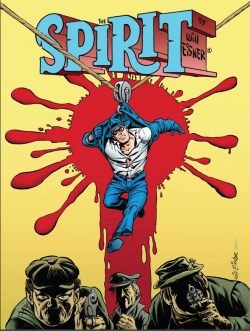

Almost all the groundbreaking extended epic was crafted by scripter Denny O’Neil, veteran illustrator Curt Swan and inker Murphy Anderson – although stand-in Dick Giordano inked #240. The willing and very public abandonment of super-villains, Kryptonian scenarios and otherworldly paraphernalia instantly revitalised the Man of Tomorrow, attracted new readers and began a period of superb human-scaled stories which made him a “must-buy†character all over again.

The innovations began in ‘Superman Breaks Loose’ (Superman #233) when a government experiment to harness the energy of Kryptonite goes explosively wrong. Closely monitoring the test, the Action Ace is blasted across the desert surrounding the isolated lab but somehow survives the supposedly fatal radiation-bath. In the aftermath reports start to filter in from all over Earth: every piece of the deadly green mineral has been transformed to common iron…

As he goes about his protective, preventative patrols, the liberated hero experiences an emotional high at the prospect of all the good he can do now. He isn’t even phased when the Daily Planet‘s new owner Morgan Edge (a key Kirby character) shakes up his civilian life: summarily ejecting Clark Kent from the print game and overnight remaking him into a roving TV journalist…

Meanwhile in the deep desert, the site of his recent crashlanding offers a moment of deep foreboding when Superman’s irradiated imprint in the sand shockingly grows solid and shambles away in ghastly parody of life…

The resurgent suspense resumes in #234’s ‘How to Tame a Wild Volcano!’, as an out-of-control plantation owner refuses to let his indentured native workforce flee an imminent eruption. Handicapped by misused international laws, the Man of Tomorrow can only fume helplessly as the UN rushes towards a diplomatic solution, but his anxiety is intensified when the sinister sand-thing inadvertently passes him and agonisingly drains him of his mighty powers.

Crashing to Earth in a turbulent squall, the de-powered hero is attacked by bossman Boysie Harker‘s thugs and instantly responds to the foolish provocation, relying for a change on determination rather than overwhelming might to save the day…

The ‘Sinister Scream of the Devil’s Harp’ in #235 gave way to weirder ways (the industry was enjoying a periodic revival of interest in supernatural themes and stories) as mystery musician Ferlin Nyxly reveals the secret of his impressive and ever-growing aptitudes is an archaic artefact which steals gifts, talents and even Superman’s alien abilities.

The Man of Steel is initially unaware of the drain as he’s trying to communicate with his eerily silent dusty doppelganger, but once Nyxly graduates to a full-on raving super-menace self-dubbed Pan, the taciturn homunculus unexpectedly joins its living template in trouncing the power thief…

The next issue offered a science fictional morality play as cherubic aliens seek Superman’s assistance in defeating a band of devils and rescuing Clark Kent’s best friends from Hell. However, the ‘Planet of the Angels’ proves to be nothing of the kind, and the Caped Kryptonian has to pull out all the stops to save Earth from a very real Armageddon…

Superman #237 sees the Metropolis Marvel save an astronaut only to see him succumb to a madness-inducing mutative disease. After another destructive confrontation with the sand-thing further debilitates him, the harried hero is present when more mortals fall to the contagion and – believing himself the cause and an uncontrollable ‘Enemy of Earth’ – considers quarantining himself to space…

As he is deciding, Lois Lane stumbles into one more lethal situation and Superman’s instinctive intervention seemingly confirms his earlier diagnosis, but another clash with his always-close sandy simulacrum on the edge of space heralds an incredible truth. Pathetically debilitated, Superman nevertheless saves Lois and again meets the ever-more human creature. Now able to speak, it gives a chilling warning and the Man of Steel realises exactly what it is taking from him and what it might become…

A mere shadow of his former self, the Man of Tomorrow is unable to prevent a band of terrorists taking over a magma-tapping drilling rig and endangering the entire Earth in #238’s ‘Menace at 1000 Degrees’. With Lois one of a number of hostages and the madmen threatening to detonate a nuke in the pipeline, the Action Ace desperately begs his doppelganger to assist him, before its cold rejection forces the depleted hero to take the biggest gamble of his life…

Superman #239 was an all-reprint giant featuring the hero in his incalculably all-powerful days – and thus not included here – but the much-reduced Caped Kryptonian returned in #240 (Giordano inks) to confront his own lessened state and seek a solution in ‘To Save a Superman’. The trigger is his inability to extinguish a tenement fire and the wider world’s realisation that their unconquerable champion was now vulnerable and fallible…

Especially interested are his old enemies in the Anti-Superman Gang who immediately allocate all their resources to destroying their nemesis. After one particularly close call Clark is visited by an ancient Asian sage who somehow knows of his other identity and offers an unconventional solution…

From 1968 onwards superhero comics began to decline and publishers sought new ways to keep audience as tastes changed. Back then, the entire industry depended on newsstand sales, and if you weren’t popular, you died. Editor Jack Miller, innovating illustrator Mike Sekowsky and relatively new scripter Denny O’Neil stepped up with a radical proposal and made a little bit of funnybook history with the only female superhero then in the marketplace.

They revealed that the almighty mystical Amazons were forced to leave our dimension, and took with them all their magic – including Wonder Woman‘s powers and all her weapons…

Reduced to mere humanity she opted to stay on Earth, assuming her own secret identity of Diana Prince, resolved to fighting injustice as a mortal. Tutored by blind Buddhist monk I Ching, she trained as a martial artist, and quickly became a formidable enemy of contemporary evil.

Now this same I Ching claims to be able to repair Superman’s difficulties and dwindling might, but evil eyes are watching. Arriving clandestinely, Superman allows the adept to remove all his Kryptonian powers as a precursor to restoring them, allowing the A-S Gang the perfect opportunity to strike. In the resultant melee, the all-too-human hero triumphs in the hardest fight of his life…

The saga continues with “Swan-derson†back on the art in #241 as Superman overcomes a momentary but nearly overwhelming temptation to surrender his oppressive burden and lead a normal life…

Admonished and resolved, he then submits to Ching’s resumed remedy ritual and finds his spirit soaring to where the sand-being lurks before explosively reclaiming the stolen powers. Leaving the gritty golem a shattered husk, the phantom brings the awesome energies back to their true owner and a triumphant hero returns to saving the world…

Over the next few days, however, it becomes clear that something has gone wrong. The Man of Tomorrow has become arrogant, erratic and unpredictable, acting rashly, overreacting and even making stupid mistakes.

In her boutique Diana Prince discusses the problem with Ching and the sagacious teacher soon deduces that during his time of mere mortality whilst fighting the gangsters, Superman received a punishing blow to the head. Clearly it has resulted in brain injury that did not heal when his powers returned…

When the hero refuses to listen to them, Diana and Ching have no choice but to track down the dying sand-thing and request its aid. The elderly savant recognises it as a formless creature from other-dimensional realm Quarrm and listens to the amazing story of its entrance into our world. He also suggests a way for it to regain some of what it recently lost…

Superman, meanwhile, has blithely gone about his deranged business until savagely attacked by the possessed and animated statue of a Chinese war-demon. Also able to steal his power, this second fugitive from Quarrm has no conscience and wears ‘The Shape of Fear!…

The staggering saga concludes in ‘The Ultimate Battle’ as the Quarrmer briefly falls under the sway of a brace of brutal petty thugs who put the again de-powered Superman into hospital…

Rushed into emergency surgery, the Kryptonian fights for his life as the sand-thing confronts the war-demon in the streets, but events take an even more bizarre turn once the latter drives off its foe and turns towards the hospital to finish off the flesh-&-blood Superman.

Recovering consciousness – and a portion of his power – the Metropolis Marvel battles the beast to a standstill but needs the aid of his silicon stand-in to drive the thing back beyond the pale…

With the immediate threat ended, Man of Steel and Man of Sand face each other one last time, each determined to ensure his own existence no matter the cost…

The stunning conclusion was a brilliant stroke on the part of the creators, one which left Superman approximately half the man he used to be. Of course, all too soon he returned to his unassailable, god-like power levels but never quite regained the tension-free smug assurance of his 1950s-1960s self.

A fresh approach, snappy dialogue and more terrestrial, human-scaled concerns to shade the outrageous implausible fantasy elements, wedded to gripping plots and sublime artwork make Kryptonite Nevermore! one of the very best Superman sagas ever created.

Also included here is the iconic ‘House Ad’ by Swan & Vince Colletta which proclaimed the big change throughout the DC Universe, and a thoughtful ‘Afterword by Denny O’Neil’ wraps things up with some insights and reminiscences every lover of the medium will appreciate.

© 1971, 2009 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved.