By Goscinny and Uderzo, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Hodder/Dargaud, Hodder and Stoughton, Orion Books)

ISBN: 978-0-34039-772-0 & 978-0-34027-647-1

One of the most-read comics series in the world, the chronicles of Asterix the Gaul have been translated into more than 100 languages; with eight animated and four live-action movies, TV series, assorted toys and games and even a theme park (Parc Astérix, near Paris, naturellement).

More than 325 million copies of the 35 canonical Asterix books have sold worldwide, making Goscinny & Uderzo France’s bestselling international authors.

Their diminutive, doughty hero was created in 1959 by two of the art-form’s greatest proponents, René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo; masters of strip narrative then at the peak of their creative powers. Although their perfect partnership ended in 1977 with the death of prolific scripter Goscinny, the creative wonderment continued with Uderzo writing and drawing the feature until his retirement in 2010.

In 2013 a new adventure – Asterix and the Picts – opened a fresh chapter in the annals as Jean-Yves Ferri & Didier Conrad began their much anticipated and dreaded continuation of the franchise.

Like everything good, the core premise works on multiple levels: ostensibly, younger readers enjoy the action-packed, lavishly illustrated comedic romps where conniving, bullying baddies get their just deserts, whilst more worldly readers enthuse over the dry, pun-filled, slyly witty satire, enhanced for English speakers by the brilliantly light touch of translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who played no small part in making the indomitable Gaul so palatable to the Anglo-Saxon world. (Personally I still thrill to a perfectly delivered punch in the bracket as much as a painfully swingeing string of bad puns and dry cutting jibes…)

Asterix the Gaul is a cunning underdog who resists the iniquities, experiences the absurdities and observes the myriad wonders of Julius Caesar‘s Roman Empire with brains, bravery and a bit of magic potion.

The stories were alternately set on the tip of Uderzo’s beloved Brittany coast, where a small village of redoubtable warriors and their families resisted every effort of the Roman Empire to complete their conquest of Gaul or throughout the expansive Ancient World circa 50BC.

Unable to defeat this last bastion of Gallic insouciance, the mostly victorious invaders resorted to a policy of cautious containment. Thus the little seaside hamlet is permanently hemmed in by the heavily fortified garrisons of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.

The Gauls don’t care: they daily defy the world’s greatest military machine by just going about their everyday affairs, protected by the magic potion of resident druid Getafix and the shrewd wits of a rather diminutive dynamo and his simplistic best friend…

Firmly established as a global brand and premium French export by the mid-1960s, Asterix the Gaul continued to grow in quality as Goscinny & Uderzo toiled ever onward, crafting further fabulous sagas; building a stunning legacy of graphic excellence and storytelling gold.

René Goscinny was one of the most prolific, and remains one of the most read, writers of comic strips the world has ever seen. Born in Paris in 1926, he was raised in Argentina where his father taught mathematics. From an early age the boy showed artistic promise, and studied fine arts, graduating in 1942.

While working as junior illustrator in an ad agency in 1945 an uncle invited him to stay in America, where he found work as a translator. After his National Service in France Goscinny settled in Brooklyn and pursued an artistic career, becoming in 1948 an art assistant in a little studio which included Harvey Kurtzman, Will Elder, Jack Davis and John Severin as well as a couple of European giants-in-waiting: Maurice de Bévère (“Morrisâ€, with whom he produced Lucky Luke from 1955-1977) and Joseph Gillain (Jijé).

He also met Georges Troisfontaines, head of the World Press Agency, the company that provided comics for the French magazine Spirou.

After contributing scripts to Belles Histoires de l’Oncle Paul and ‘Jerry Spring’ Goscinny was made head of World Press’ Paris office, where he first met his life-long creative partner Albert Uderzo (Jehan Sepoulet, Luc Junior) as well as creating Sylvie and Alain et Christine (with “Martialâ€- Martial Durand) and Fanfan et Polo (drawn by Dino Attanasio).

In 1955 Goscinny, Uderzo, Charlier and Jean Hébrard formed the independent Édipress/Édifrance syndicate, creating magazines for general industry (Clairon for the factory union and Pistolin for a chocolate factory). With Uderzo he produced Bill Blanchart, Pistolet and Benjamin et Benjamine, whilst himself writing and illustrating Le Capitaine Bibobu.

Goscinny seems to have invented the 9-day week. Under the pen-name Agostini he wrote Le Petit Nicholas (drawn by Jean-Jacques Sempé) and in 1956 began an association with the revolutionary comics magazine Tintin, writing stories for many illustrators including Signor Spagetti (Dino Attanasio), Monsieur Tric (Bob De Moor), Prudence Petitpas (Maréchal), Globule le Martien and Alphonse (both by Tibet), Modeste et Pompon (for André Franquin), Strapontin (Berck) as well as Oumpah-Pah with Uderzo.

He also wrote strips for the magazines Paris-Flirt and Vaillant.

In 1959 Édipress/Édifrance launched Pilote and Goscinny went into overdrive. The first issue starred his and Uderzo’s instant masterpiece Asterix the Gaul, began Jacquot le Mousse and Tromblon et Bottaclou (drawn by Godard) and also re-launched Le Petit Nicolas and Jehan Pistolet/Jehan Soupolet.

When Georges Dargaud bought Pilote in 1960, Goscinny became editor-in-Chief, but still found time to add new series Les Divagations de Monsieur Sait-Tout (Martial), La Potachologie Illustrée (Cabu), Les Dingodossiers (Gotlib) and La Forêt de Chênebeau (Mic Delinx).

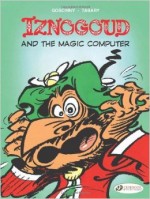

He also wrote frequently for television. In his spare time he created a little strip entitled Les Aventures du Calife Haroun el Poussah for Record (first episode January 15th 1962) illustrated by a Swedish-born artist named Jean Tabary. A minor success, it was re-tooled as Iznogoud when it transferred to Pilote.

Goscinny died – probably of well-deserved pride and severe exhaustion – aged 973, in November 1977.

In the post-war rebuilding of France, Albert Uderzo returned to Paris and became a successful artist in the country’s burgeoning comics industry. His first published work, a pastiche of Aesop’s Fables, appeared in Junior, and in 1945 he was introduced to industry giant Edmond-François Calvo (whose own masterpiece The Beast is Dead is long overdue for a new edition…).

The tireless Uderzo’s subsequent creations included the indomitable eccentric Clopinard, Belloy, l’Invulnérable, Prince Rollin and Arys Buck. He illustrated Em-Ré-Vil’s novel Flamberge, worked in animation, as a journalist and illustrator for France Dimanche, and created the vertical comicstrip ‘Le Crime ne Paie pas’ for France-Soir. In 1950 he even illustrated a few episodes of the franchised European version of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Jr. for Bravo!

An inveterate traveller, the prodigy met Rene Goscinny in 1951. Soon fast friends, they decided to work together at the new Paris office of Belgian Publishing giant World Press. Their first collaboration was in November of that year; a feature piece on savoir vivre (how to live right or gracious living) for women’s weekly Bonnes Soirée, after which an avalanche of splendid strips and serials poured forth.

Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior were created for La Libre Junior and they produced a western starring a Red Indian (ah, simpler, if more casually racist, times…) who eventually evolved into the delightfully infamous Oumpah-Pah. In 1955 with the formation of Édifrance/Édipresse, Uderzo drew Bill Blanchart for La Libre Junior, replaced Christian Godard on Benjamin et Benjamine and in 1957 added Charlier’s Clairette to his portfolio.

The following year later, he made his debut in Tintin, as Oumpah-Pah finally found a home and a rapturous, devoted audience. Uderzo also drew Poussin et Poussif, La Famille Moutonet and La Famille Cokalane.

When Pilote launched in 1959 Uderzo was a major creative force for the new magazine collaborating with Charlier on Les Aventures de Tanguy et Laverdure and launching with Goscinny a little something called Asterix…

Although Asterix was a massive hit from the start, Uderzo continued working on Tanguy et Laverdure, but soon after the first adventure was collected as Ast̩rix le gaulois in 1961 it became clear that the series would demand most of his time Рespecially as the incredible Goscinny never seemed to require rest or run out of ideas.

By 1967 the strip occupied all Uderzo’s attention, so in 1974 the partners formed Idéfix Studios to fully exploit their inimitable creation. When Goscinny passed away three years later, Uderzo had to be convinced to continue the adventures as writer and artist, producing a further ten volumes until he retired.

That year, after nearly 15 years as a weekly comic strip subsequently collected into compilations, the 21st tale (Asterix and Caesar’s Gift) was the first to be published as a complete original album before being serialised. Thereafter each new release was a long anticipated, eagerly awaited treat for the strip’s millions of fans…

According to UNESCO’s Index Translationum, Uderzo is the tenth most-often translated French-language author in the world and the third most-translated French language comics author – right after his old mate René Goscinny and the grand master Hergé.

As one of the most popular comics on Earth, Asterix has naturally become something of a celluloid star too and, the business being what it is, some of those movie megaliths have been recycled into intriguing – if non-canonical – graphic albums in their own right.

Although technically apart from the accepted legend, those filmic tomes are well worth a look too…

In 1976 The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (originally entitled Les Douze travaux d’Astérix) was the very first theatrical release: an animated feature written, created, Directed and Produced by Goscinny & Uderzo’s own company Studios Idéfix.

Like the albums which inspired it, the tale saw Asterix and Obelix undertake a long voyage into the unknown: one packed with exotic climes, odd people and boldly surreal adventure – although the topical lampooning and satire were subtly dialled back.

More a studio-produced illustrated prose storybook than a comic strip, this “book of the film†naturally introduces our bucolic cast before diving into the rather clever plot wherein the perennially bashed-up Roman Legions surrounding the village of Indomitable Gauls come to the scary conclusion that their devil-may-care foes must be gods…

When the rumours reach the Roman Senate, Julius Caesar is livid. Determined to quell the deadly talk before his power crumbles, he personally travels to the little village and challenges the Gallic resistors. If they can accomplish twelve labours as arduous as those undertaken by Hercules, they will have proved themselves gods and he will give them the entire empire and retire…

Enthralled more by the challenge than the possible outcome, chief Vitalstatistix nominates Asterix and Obelix to travel to Rome and tackles Caesar’s challenge. With diminutive scribe Caius Tiddlus accepted as official referee and recorder, the easy-going competitors set about the cunning list of labours devised by Caesar’s devious Councillors, beginning with ‘Running Faster than Asbestos, Champion of the Olympic Games‘.

Thanks to a sip of magic potion Asterix humiliatingly and hilariously outdistances the racer after which Obelix ‘Throws a Javelin Farther than Verses the Persian’.

Although the sportsman’s best effort lands in faraway undiscovered America (at the feet of Oompah-pah), Obelix’ javelin never lands at all but goes into a very, very low orbit around the Earth…

The third task – ‘Beating Cilindric, the German’ – is far harder to handle. The tiny warrior is a master martial artist who easily lobs Obelix all over the landscape but his stiff-necked formality makes him easy prey for Asterix’ guile…

Task four is to ‘Cross a Lake’ but in the centre is an Isle of Pleasure inhabited by beguiling Sirens where the affable lads are quickly enchanted. They would be there still if the lovely ladies had served Wild Boar instead of just Nectar and Ambrosia…

In short order the Gauls ‘Survive the Hypnotic Gaze of Iris the Egyptian’ and ‘Finish a Meal made by Calorofix the Belgian’, infamous for cooking huge meals for the godly progenitors known as The Titans.

Obelix eagerly tackles the mountain of nosh and breaks the culinary wizard’s spirit by consuming every morsel and innocently asking what the main course is…

The going gets tough and weird when the pair have to ‘Survive the Cave of the Beast’ and then battle bureaucracy gone wild by ‘Finding Permit A38 in “The Place That Sends You Mad‒, thereafter ‘Crossing a Ravine on an Invisible Tightrope, over a River full of Crocodiles’, ‘Climbing a Mountain and Answering the Old Man’s Riddle’ (a task which so impresses the actual gods that Jupiter causes a thunderstorm) before the weary contestants move on to their final task of the day by ‘Spending a Night on the Haunted Plains’.

Tragically for the restless spirits, the Gauls aren’t afraid of Roman soldiers, living or dead…

Next morning Asterix and Obelix awaken outside Caesar’s Palace in Rome and learn that their Twelfth Task is simply to ‘Survive the Circus Maximus’. The emperor is taking no chances however, and has gathered all the other Gaulish villagers to share what he thinks will be their spectacular demise at the hands of his gladiators and the fangs and claws of every savage beast in the city.

It seemed such a perfect plan, but Caesar’s soldiers really should have made sure that Druid Getafix couldn’t whip up some magic potion…

Astérix et la surprise de César was an animated feature released in 1985, the fourth film in a burgeoning franchise. The story was cobbled together from elements of the albums Asterix the Legionary and Asterix the Gladiator by Goscinny & Uderzo’s great friend screenwriter Pierre Tchernia.

I’m not sure if the translated Asterix Versus Caesar had a full cinema release in this country, but the book certainly seemed to be everywhere in 1986: a lovely large full colour hardback wedding another peerless prose adaptation to a wealth of stills (and a few fascinating design and models sheets) from the movie into a splendid, rollicking rollercoaster romp…

When Vitalstatistix’ beautiful niece Panacea visits the village, everybody is astonished to find that oafish Obelix is off his food. The colossal simpleton is hopelessly in love with the charming girl, who typically only has eyes for hunky Tragicomix, son of neighbouring chief Dramatix.

The hopeless situation takes a turn for the very worst though when the happy couple are kidnapped by the Romans. After the enraged, potion-powered villagers register their protests in the usual manner, a battered centurion informs them Panacea and Tragicomix have already been shipped to Condatum where the boy will be sent to fight in a Foreign Legion unit.

Hard on their heels Asterix and Obelix (accompanied by noble if diminutive canine wonder Dogmatix) beat, bully and trick their way into the Roman army, following the kidnapped lovers to Arabia as full-fledged legionaries. On arrival they discover that Panacea and Tragicomix have already escaped, been captured by Bedouins and sold to unctuous functionary Caius Flabius Obtus for a proposed ceremonial Triumph for Julius Caesar.

In Rome!

As the separated lovers languish in dank Roman dungeons, Asterix and Obelix hot-foot it for the Eternal City and, after contriving to become slaves, managed to get themselves into Obtus’ Gladiatorial School before their plans suffer a setback when Asterix mislays his flask of magic potion.

With Asterix and Obelix – mostly Obelix – defeating all combative comers at Caesar’s Triumph, everything tensely culminates in a grim showdown at the Colosseum with Tragicomix about to die under the claws of massed lions until valiant Dogmatix dashes into the arena, dragging that gourd of potion…

After literally bringing the house down, the quartet of Gauls confront Caesar, who has no choice but to allow them to return to their own land and a traditional welcome home feast…

Although eschewing the sly pokes and good-natured joshing, famous caricatures and wry commentary, these gentle all-ages tales will easily charm younger readers into the raucous, bombastic, bellicose hi-jinks and fast-paced action which never fails to astound and bemuse fans of those Fantastic French Fellows who always prove that potion-powered Gallic Pride is safe in steady hands whether you’re operating a video remote or merely turning perfect pages…

The Twelve Tasks of Asterix © Dargaud Editeur 1976 Goscinny-Uderzo. English translation © 1978 Hodder and Stoughton Ltd. All rights reserved.

Asterix Versus Caesar © 1985 Editions Albert René, Goscinny & Uderzo. English translation © 1986 Hachette. All rights reserved.