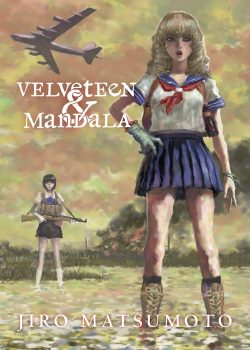

By Jiro Matsumoto (Vertical)

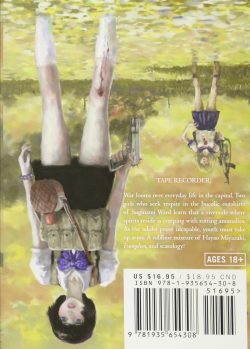

ISBN: 978-1-935654-30-8 (TankÅbon PB)

Things have been a bit too much sweetness and light around here lately. Here’s a change of pace and taste then then needs a bit of an advisory warning. This book revels in gratuitous violence, barely-closeted misogyny and sexualised imagery. So why, then, is it so very good?

Civilisation has radically changed. What we knew is no longer right or true, but disturbing remnants remain to baffle and terrify, as High School girl Velveteen and her decidedly off-key classmate and companion/enemy Mandala eke out an extreme existence on the banks of a river in post-Zombie-Apocalypse Tokyo.

Here (with straight-faced nods to Tank Girl), using an abandoned battle-wagon as their crash-pad, the girls while away the days and nights casually slaughtering roaming hordes of zombies – at least whenever they can stop squabbling with each other…

From the very outset of this grim, sexy, gratuitous splatter-punk horror-show there is something decidedly “off†going on: a gory mystery beyond the usual “how did the world end this time?â€

On the surface, Velveteen & Mandala (Becchin To Mandara in its original 14-chapter run between 2007-2009 in the periodical Manga Erotics F) is a monster-killing yarn which owes plenty to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but there’s more than meets the eye or ballistic charge happening here.

We begin at ‘The Riverside’ with the pair awaking from dreams to realise and remember the hell they now inhabit. Cunning catch-up concluded, ‘Smoke on the Riverside’ then reveals a few of the nastier ground-rules of their current lifestyle, and especially Velveteen’s propensity for arson and appetite for destruction…

‘Sukiyaki’ finds the girls on edge as food becomes an issue, whilst the introduction of ‘The Super’ who monitors their rate of zombie dispatch leads to more information (but not necessarily any answers) in this enigmatic world, after which ‘The Cellar’ amps up the uncertainty as Velveteen steals into her new boss’s ghastly man-cave inner sanctum…

In a medium where extreme violence is commonplace, Matsumoto increasingly uses unglamourised nudity and brusque vulgarity to unsettle and shock the reader, but the flashback events of … ‘School Arcade, Underground Shelter’ – if true and not delusion – indicate that a society this debased might not be worth saving from the undead…

In ‘Omen’ and ‘Good Omen (Whisper)’ the obfuscating mysteries begins to clear as B52 bombers dumps thousands more corpses by the Riverside, adding to the “to do†roster of walking dead the girls must deal with once darkness falls…

Throughout the story Matsumoto liberally injects cool artefacts of fashion, genre and pop-culture seemingly at random, but as the oppressive horrors get ever closer to ending our heroines in ‘Genocide’ and ‘Deep in the Dark’, a certain sense can be imagined, so that once the Super is removed and Velveteen promoted to his position in ‘Parting’, the drama spirals into a hallucinogenic – possibly untrustworthy – climax for ‘Mandala’s Big Farewell Party’ and ‘Nirvana’ before the further revelations of ‘Flight’…

Deliberately misleading and untrustworthy – and strictly aimed at over-18s – this dark, nasty, scatologically excessive tale graphically celebrates the differences between grotesque, flesh-eating dead-things and the constantly biologically mis-functioning Still-Living (although the zombie “Deadizens†are still capable of cognition, speech and rape…); all wrapped up in the culturally acceptable and traditional manner of one blowing the stuffings out of the other…

Confirmed confrontationalist Jiro Matsumoto (Uncivilized Planet, Avant-Pop Mars, A Revolutionist in the Afternoon, Tropical Citron) is probably best known for dystopian speculative sci-fi revenge thriller Freesia, but here his controversial yet sublime narrative gifts are turned to a much more psychologically complex – almost meta-fictional – layering of meaning upon revelation upon contention, indicating that if you have a strong enough stomach the very best is still to come…

First seen in English as a monochrome paperback in 2011, this stand-alone saga will be available in digital formats later this year.

© 2009 Jiro Matsumoto. All right reserved. Translation © 2011 Vertical, Inc.