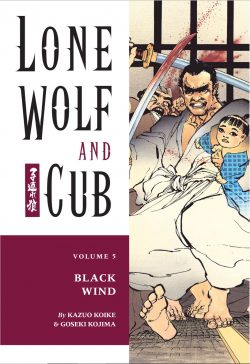

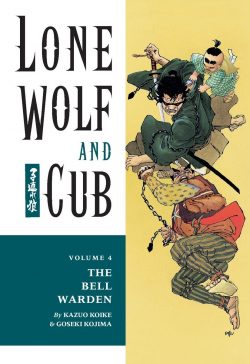

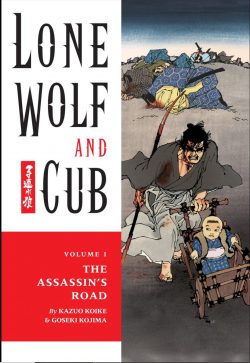

By Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima, translated by Dana Lewis (Dark Horse Manga)Â

ISBN: 978-1-56971-505-5 (TPB/digital edition)Â

Best known in the West as Lone Wolf and Cub, the epic Samurai saga created by Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima is without doubt a global classic of comics literature. An example of the popular “Chanbara†or “sword-fighting†genre of print and screen, Kozure Okami was serialised in Weekly Manga Action from September 1970 until April 1976. It was an immense and overwhelming “Seinen†(“Men’s mangaâ€) hit…Â

The tales prompted thematic companion series Kubikiri Asa (Samurai Executioner) which ran from 1972-1976, but the major draw – at home and, increasingly, abroad – was always the nomadic wanderings of doomed noble ÅŒgami IttÅ and his solemn, silent child.Â

Revered and influential, Kozure Okami was followed after years of supplication by fans and editors by sequel Shin Lone Wolf & Cub (illustrated by Hideki Mori) and even spawned – through Koike’s indirect participation – science fiction homage Lone Wolf 2100 by Mike Kennedy & Francisco Ruiz Velasco.Â

The original saga has been successfully adapted to most other media, spawning movies, plays, TV series (plural), games and merchandise. The property is infamously still in Hollywood pre-production.Â

The several thousand pages of enthralling, exotic, intoxicating narrative art produced by these legendary creators eventually filled 28 collected volumes, beguiling generations of readers in Japan and, inevitably, the world. More importantly, their philosophically nihilistic odyssey – with its timeless themes and iconic visuals – has influenced hordes of other creators. The many manga, comics and movies these stories have inspired around the globe are impossible to count. Frank Miller, who illustrated the cover of this edition, referenced the series in Daredevil, his dystopian opus Ronin, The Dark Knight Returns and Sin City. Max Allan Collin’s Road to Perdition is a proudly unashamed tribute to the masterpiece of vengeance-fiction. Stan Sakai has superbly spoofed, pastiched and celebrated the wanderer’s path in his own epic Usagi Yojimbo, and even children’s cartoon shows such as Samurai Jack are direct descendants of this astounding achievement of graphic narrative. The material has become part of a shared world culture.Â

In the West, we first saw the translated tales in 1987, as 45 Prestige Format editions from First Comics. That innovative trailblazer foundered before getting even a third of the way through the vast canon, after which Dark Horse Comics assumed the rights, systematically reprinting and translating the entire epic into 28 tankÅbon-style editions of about 300 pages each, between September 2000-December 2002. Once the entire epic was translated, it was all placed online through the Dark Horse Digital project.Â

Following a cautionary ‘Note to Readers’ – on stylistic interpretation – this moodily morbid monochrome collection truly gets underway, keeping many terms and concepts western readers may find unfamiliar. Therefore this edition offers at the close a Glossary providing detailed context on the term used in the stories, plus profiles of author Koike Kazuo & illustrator Kojima Goseki and another instalment of ‘The Ronin Report’ by Tim Ervin-Gore. The occasional series of articles here offers a rundown on exotic weaponry of the era in Weapons Glossary: Part one… Â

Set in the era of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the saga concerns a foredoomed wandering killer who was once the Shogun’s official executioner: capable of cleaving a man in half with one stroke. An eminent individual of esteemed imperial standing, elevated social position and impeccable honour, ÅŒgami IttÅ lost it all and now roams feudal Japan as a doomed soul hellbent for the dire, demon-haunted underworld of Meifumado.Â

When the noble’s wife was murdered and his clan dishonoured due to the machinations of the treacherous, politically ambitious Yagyu Clan, the Emperor ordered ÅŒgami to commit suicide. Instead, he rebelled, choosing to be a despised Ronin (masterless samurai) assassin, pledged to revenge himself until all his betrayers were dead …or Hell claimed him. His son, toddler Daigoro, also chose the path of destruction and together they roam grimly evocative landscapes of feudal Japan, one step ahead of doom, with death behind and before them.Â

Unflinching formula informs early episodes: the acceptance of a commission to kill an impossible target necessitates forging a cunning plan where relentless determination leads to inevitable success. Throughout each episode plot is underscored with bleak philosophical musings alternately informed by Buddhist teachings in conjunction with or in opposition to the unflinching personal honour code of Bushido…Â

That tactic is eschewed for a simple commission in opening tale ‘Tsuji Genshichi the Bell Warden’ with the assassin hired by a prestigious and honourable official. Greater Edo runs to the timetable of nine great bells, dictating the flow of civilised time and acting as emergency alarm system in times of crisis. All that power and responsibility is controlled by one man: The Bell Warden.Â

As with most hereditary official posts, great glory and vast wealth inevitably accrues to the position, but now the aging incumbent is preparing his successor. He has three candidates and grave misgivings about the worth and dedication of each. His solution: hire the most infamous outlaw in Japan to chop off the right (bell-ringing) arm. If they can’t survive and overcome they are none of them the man for the job…Â

Drowning in his own ocean of duty, ÅŒgami accepts the commission and isn’t surprised to discover there is a hidden agenda in play…Â

As the nation modernised – or lost its ethical core – noble samurai economised by firing their retainers and hiring domestic mercenaries. As this new class – “Chugen-Gashira†– grew in power, they feathered their own nests; increasingly turning to villainy and chicanery, further debasing Japan’s moral core. They were shielded by their own base-born origins, since upholders of the old ways could not “punch down†to retaliate. Â

In ‘Unfaithful Retainers’, when two noble children seek redress for their father’s assault, the Lone Wolf also falls foul of his own entrenched self-image, and must concoct a byzantine scheme to reach the guilty party and deliver honourable justice… Â

Daigoro takes centre stage in ‘Parting Frost’ as his father goes missing during a mission. As his supplies run out and winter snows start to melt , the boy is compelled to strike out in search of his father, only to encounter a Samurai who discerns exactly who and what he is. Testing the child to destruction with fire and steel, obsessive Iki Jizamon is only foiled by the abrupt return of the cub’s far from happy sire…Â

Set in a brutal uncompromising world of privilege and misogyny, these episodes are unflinching and explicit in their treatment of violence – especially sexual violence. In detailing another historical aspect of the culture, ‘Performer’ focusses on a particular underclass: GÅmune. The term grouped together all street folk who busked for money: female minstrels, dancers, sleight-of-hand conjurers, weapons-demonstrators, kabuki actors, drummers, travelling players puppeteers, preachers, contortionists, storytellers acrobat and countless others all entertaining for coins. Naturally, they had no protection under law and when a swordswoman martial artist was brutalised by woman-hating warrior using treachery and hypnotism, she was unavenged…Â

In her shame and fury, O-Yuki had her body further desecrated by horrific, attention-diverting tattoos, giving her a momentary advantage as she butchered a succession of Samurai on her way to finding one in particular…Â

Accepting a commission from a lord rapidly being depleted of soldier-servants, ÅŒgami plays detective but finds himself deeply conflicted when he finally corners his prey. However, his given word is inviolate, his philosophy is unflinching and a job must be done…Â

These stories are deeply metaphorical and work on many levels most of us westerners just won’t grasp on first reading – even with contextual aid provided by the bonus features. That only makes them more exotic and fascinating. Also a little unsettling is the even-handed treatment of women in the tales. Within the confines of the notoriously stratified culture being depicted, females – from servants to courtesans, prostitutes to highborn ladies – are all fully rounded characters, with their own motivations and drives. The wolf’s female allies are valiant and dependable, and his foes, whether targets or mere enemy combatants in his path, are treated with professional respect. He kills them just as if they were men…Â

Whichever English transliteration you prefer – Wolf and Baby Carriage is what I was first introduced to – Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima’s grandiose, thought-provoking, hell-bent Samurai tragedy is one of those too-rare breakthrough classics of global comics literature. A breathtaking tour de force, these are comics you must not miss.Â

© 1995, 2000 Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima. All other material © 2000 Dark Horse Comics, Inc. Cover art © 2000 Frank Miller. All rights reserved.Â