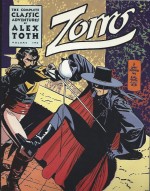

By Alex Toth & anonymous (Eclipse Books)

ISBNs: 0-913035-41-6 and 0-913035-51-3

Alex Toth was a master of graphic communication who shaped two different art-forms and is largely unknown in both of them.

Born in New York in 1928, the son of Hungarian immigrants with a dynamic interest in the arts, Toth was something of a prodigy and after enrolling in the High School of Industrial Arts doggedly went about improving his skills as a cartoonist. His earliest dreams were of a quality newspaper strip like Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates, but his uncompromising devotion to the highest standards soon soured him on newspaper strip work when he discovered how hidebound and innovation-resistant the family values-based industry had become whilst he was growing up.

Aged 15, he sold his first comicbook works to Heroic Comics and after graduating in 1947 worked for All American/National Periodical Publications (who would amalgamate and evolve into DC Comics) on Dr. Mid-Nite, All Star Comics, the Atom, Green Lantern, Johnny Thunder, Sierra Smith, Johnny Peril, Danger Trail and a host of other features. On the way he dabbled with newspaper strips (see Casey Ruggles: the Hard Times of Pancho and Pecos) but was disappointed o find nothing had changed…

Continually striving to improve his own work he never had time for fools or formula-hungry editors who wouldn’t take artistic risks. In 1952 Toth quit DC to work for “Thrilling†Pulps publisher Ned Pines who was retooling his prolific Better/Nedor/Pines comics companies (Thrilling Comics, Fighting Yank, Doc Strange, Black Terror and many more) into Standard Comics: a publishing house targeting older readers with sophisticated, genre-based titles.

Beside fellow graphic masters Nick Cardy, Mike Sekowsky, Art Saaf, John Celardo, George Tuska, Ross Andru & Mike Esposito and particularly favourite inker Mike Peppe, Toth set the bar high for a new kind of story-telling: wry, restrained and thoroughly mature; in short-lived titles dedicated to War, Crime, Horror, Science Fiction and especially Romance.

After Simon and Kirby invented love comics, Standard, through artists like Cardy and Toth and writers like the amazing and unsung Kim Aamodt, polished and honed the genre, turning out clever, witty, evocative and yet tasteful melodramas and heart-tuggers both men and women could enjoy.

Before going into the military, where he still found time to create a strip (Jon Fury for the US army’s Tokyo Quartermaster newspaper The Depot’s Diary) he illustrated 60 glorious tales for Standard; as well as a few pieces for EC and others.

On his return to a different industry – and one he didn’t much like – Toth resettled in California, splitting his time between Western/Dell/Gold Key, such as these Zorro tales and many other movie/TV adaptations, and National (assorted short pieces such as Hot Wheels and Eclipso): doing work he increasingly found uninspired, moribund and creatively cowardly. Eventually he moved primarily into TV animation, designing for shows such as Space Ghost, Herculoids, Birdman, Shazzan!, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? and Super Friends among many others.

He returned sporadically to comics, setting the style and tone for DC’s late 1960’s horror line in House of Mystery, House of Secrets and especially The Witching Hour, and illustrating more adult fare for Warren’s Creepy, Eerie and The Rook. He redesigned The Fox for Red Circle/Archie, produced stunning one-offs for Archie Goodwin’s Batman or war comics (whenever they offered him a “good scriptâ€) and contributed to landmark or anniversary projects such as Batman: Black and White.

His later, personal works included Torpedo for the European market and the magnificently audacious swashbuckler Bravo for Adventure!

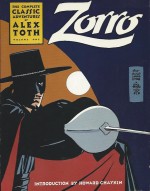

Alex Toth died of a heart attack at his drawing board on May 27th 2006 but before that the kids he’d inspired (mostly comics professionals themselves) sought to redress his shameful anonymity with a number of retrospectives and comics compilations. One of the first and best was this Eclipse Books twin set, gathering his many tales for Dell featuring Disney’s TV iteration of the prototypical masked avenger.

In 2013, Hermes Press released a lavish complete volume in full colour but, to my mind, these black and white books (grey-toned, stripped down and redrawn by the master himself) are the definitive vision and the closest to what Toth originally intended, stripped of all the obfuscating quibbles and unnecessary pictorial fripperies imposed upon his dynamic vision by legions of writing committees, timid editors and Disney franchising flacks.

One the earliest masked heroes and still phenomenally popular throughout the world, “El Zorro, The Fox†was originally devised by jobbing writer Johnston McCulley in 1919 in a five part serial entitled ‘The Curse of Capistrano’. He debuted in the All-Story Weekly for August 6th and ran until 6th September. The part-work was subsequently published by Grossett & Dunlap in 1924 as The Mark of Zorro and further reissued in 1959 and 1998 by MacDonald & Co. and Tor respectively.

Famously, Hollywood royalty Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford read the ‘The Curse of Capistrano’ in All-Story Weekly on their honeymoon and immediately optioned the adventure to be the first film release from their new production company/studio United Artists.

The Mark of Zorro was a global movie sensation in 1920 and for years after, and New York-based McCulley subsequently re-tailored his creation to match the so-different filmic incarnation. This Caped Crusader aptly fitted the burgeoning genre that would soon be peopled by the likes of The Shadow, Doc Savage and the Spider.

Rouben Mamoulian‘s 1940 filmic remake of The Mark of Zorro further ingrained the Fox into the world’s psyche and, as the prose exploits continued in a variety of publications, Dell began a comicbook version in 1949.

When Walt Disney Studios began a hugely popular Zorro TV show in 1957 (resulting in 78 half-hour episodes and four 60 minute specials before cancellation in 1961) the ongoing comics series was swiftly redesigned to capitalise on it and the entertainment corporation began a decades-long strip incarnation of “their†version of the character in various quarters of the world.

This superb set reproduces the tales produced by Toth for Dell Comics; firstly as part of the monumental try-out series Four-Color (issues #882, 920, 933, 960, 976 & 1003), and thereafter as a proven commodity with his own title – of which the restless Toth only drew #12. Other artists on the series included Warren Tufts, Mel Keefer and John Ushler and the Dell series was subsequently relaunched in January 1966 under the Gold Key imprint, reprinting (primarily) the Toth drawn material in a 9-issue run than lasted until March 1968.

Zorro – the Complete Classic Adventures Volume One opens with an effusive and extremely moving ‘Introduction by Howard Chaykin’ before steaming straight into the timeless wonder, but I thought that perhaps a brief note on the scripts might be sensible here.

As part of Disney’s license the company compelled Dell to concentrate on adapting already-aired TV episodes complete with florid, overblown dialogue and stagy, talking head shots which Toth struggled mightily – and against increasingly heated resistance from writers and editors – to pare down and liven up. Under such circumstances it’s a miracle that the strips are even palatable, but they are in fact some of the best adventure comics of the practically superhero-free 1950s.

Sadly, all the covers were photo-shots of actor Guy Williams in character so even that graphic outlet was denied Toth – and us…

One bonus however is that the short, filler stories used to supplement the screen adaptations were clearly generated in-house with fewer restrictions, so here Toth’s brilliance shines through…

The origin and set-up for the series came with Four-Color #882 (February 1958) in ‘Presenting Señor Zorro’. Retelling the first episode of the TV show, it introduces dashing swordsman Don Diego De La Vega, returning from Spain in 1820 to his home in Pueblo De Los Angeles in answer to a letter telling of injustice, corruption and tyranny…

With mute servant Bernardo – who pretends to be also deaf and acts as his perfect spy amongst the oppressors – Diego determines to assume the role of a spoiled and cowardly fop whilst creating the masked identity of El Zorro “the Fox†to overthrow wicked military commander and de facto dictator Capitan Monastario.

Shrugging off the clear disappointment of his father Don Alejandro, Diego does nothing when their neighbour Ignacio “Nacho†Torres is arrested on charges of treason but that night a masked figure in black spectacularly liberates the political prisoner and conveys him to relative safety and legal sanctuary at the Mission of San Gabriel…

The second TV instalment became the closing chapter of that first comicbook as ‘Zorro’s Secret Passage’ finds Monastario suspicious that Zorro is a member of the De La Vega household and stakes the place out. When the Commandante then accuses another man of being the Fox, Diego uses the underground passages beneath his home to save the innocent victim and confound the dictator…

Four-Color #920 (June 1958) adapted the third and fourth TV episodes, beginning with “Zorro Rides to the Mission†which became ‘The Ghost of the Mission Part One’ as Monastario discovers where Nacho Torres is hiding and surrounds the Mission. Unable to convince his lancers to break the sacred bounds of Sanctuary, the tyrant settles in for a siege and ‘The Ghost of the Mission Part Two’ sees him fabricate an Indian uprising to force his way in. Sadly for the military martinet Diego has convinced his bumbling deputy Sergeant Demetrio Garcia that the Mission is haunted by a mad monk…

Despite appearing only quarterly, Zorro stories maintained the strict continuity dictated by the weekly TV show. “Garcia’s Secret Mission†became ‘Garcia’s Secret’ in Four-Color #933 (September 1958) and saw Monastario apparently throw his flunky out of the army in a cunning plot to capture the Fox. Once again the ruse was turned against the connivers and El Capitan was again humiliated.

The last half of the issue saw a major plot development, however, as TV instalment “The Fall of Monastario†became ‘The King’s Emissary’ wherein the Commandante tries to palm off ineffectual Diego as Zorro to impress the Viceroy of California only to find himself inexplicably exposed, deposed and arrested…

The rest of this initial outing comprises a quartet of short vignettes commencing with ‘A Bad Day for Bernardo’ (Four-Color #920) wherein the unlucky factotum endures a succession of mishaps as he and Zorro search for a missing señorita and almost scotch her plans to elope, whilst Four-Color #933 provided the tale of youngster Manuelo, who ran away to become ‘The Little Zorro’. Happily Diego is able to convince the lad that school trumps heroism… in this case…

In ‘The Visitor’ (Four-Color #960, December 1958) Diego and Bernardo find a baby on their doorstep and help the mother to free her husband from jail before the volume concludes with ‘A Double for Diego’ (Four-Color #976, March 1959) wherein Sgt. Garcia – now in temporary charge of Los Angeles – seeks Diego’s help to capture Zorro, necessitating the wily hero trying to be in two places at once…

Zorro Volume Two leads off with ‘A Foreword’s Look Back and Askance’ by Alex Toth, who self-deprecatingly recaps his life and explains his artistic philosophy, struggles with Dell’s editors and constant battle to turn the anodyne goggle-box crusader back into the dark and flamboyant swashbuckler of the Mamoulian movie…

Four-Color #960 (December 1958) has TV tales “The Eagle’s Brood†and “Zorro by Proxy†transformed into visual poetry when a would-be conqueror targets Los Angeles as part of a greater scheme to seize control of California. With new Capitan Toledano despatched to seek out a vast amount of stolen gunpowder, ‘The Eagle’s Brood’ infiltrate the town, sheltered by a traitor at the very heart of the town’s ruling elite…

Made aware of the seditious plot, Zorro moves carefully against the villains, foiling their first attempt to take over and learning the identity of an untouchable traitor…

The saga resumed and concluded in ‘Gypsy Warning’ (Four-Color #976, adapting “Quintana Makes a Choice†and “Zorro Lights a Fuseâ€) as Zorro foils a plot to murder pro tem leader Garcia and stumbles into the final stages of the invasion of Santa Barbara, San Diego, Capistrano and Los Angeles…

With The Eagle temporarily defeated, short back-up ‘The Enchanted Bell’ (Four-Color #1003, June 1959) sees Zorro prevent the local tax collector confiscating a prized bell beloved by the region’s Indians to prevent a possible uprising, after which the lead story from the same issue details how ‘The Marauders of Monterey’ (adapting “Welcome to Monterey†and “Zorro Rides Aloneâ€) lure officials from many settlements with the promise of vitally needed supplies and commodities before robbing them.

Sadly for them, Los Angeles sent the astute but effete Don Diego to bid for the goods and he had his own solutions for fraud and banditry…

After more than a year away Toth returned for one last hurrah as ‘The Runaway Witness’ (Zorro #12, December 1960/February 1961) found the Fox chasing a frightened flower-girl all over the countryside. Justice rather than romance was on his mind as he sought to convince her to testify against a powerful man who had murdered his business partner… This stunning masterclass in comics excellence concludes with ‘Friend Indeed’ from the same issue wherein Zorro plays one of his most imaginative tricks on Garcia, allowing the hero to free a jail full of political prisoners…

Full-bodied, captivating and beautifully realised, these immortal adventures of a global icon are something no fan of adventure comics and thrilling stories should be without.

Zorro ® and © Zorro Productions. Stories and artwork © 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961Walt Disney Productions This edition © 1986 Zorro Productions, Inc.