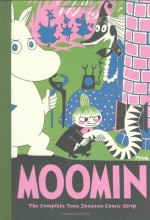

By Tove Jansson (Drawn & Quarterly)

ISBN: 978-1-897299-19-7

Tove Jansson was one of the greatest literary innovators and narrative pioneers of the 20th century: equally adept at shaping words and images to create worlds of wonder. She was especially expressive in pen and ink, manipulating slim economical lines and patterns to realise sublime realms of fascination, whilst her dexterity made simple forms into incredibly expressive and potent symbols.

Tove Marika Jansson was born into an artistic, intellectual and practically bohemian Swedish family in Helsinki, Finland on August 9th 1914. Her father Viktor was a sculptor, her mother Signe Hammarsten-Jansson a successful illustrator, graphic designer and commercial artist. Tove’s brothers Lars and Per Olov became a cartoonist/writer and photographer respectively. The family and its close intellectual, eccentric circle of friends seems to have been cast rather than born, with a witty play or challenging sitcom as the piece they were all destined to act in.

After intensive study from 1930-1938 (University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm, the Graphic School of the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and L’Ecole d’Adrien Holy and L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris) Tove became a successful exhibiting artist through the troubled period of the Second World War.

Intensely creative in many fields, she published the first fantastic Moomins adventure in 1945: Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (The Little Trolls and the Great Flood or latterly and more euphoniously The Moomins and the Great Flood), a whimsical epic of gentle, inclusive, accepting, understanding, bohemian, misfit trolls and their strange friends…

A young over-achiever, from 1930-1953 Tove worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for the Swedish satirical magazine Garm, and achieved some measure of notoriety with an infamous political sketch of Hitler in nappies that lampooned the Appeasement policies of Chamberlain and other European leaders in the build-up to World War II. She was also an in-demand illustrator for many magazines and children’s books. She had also started selling comic strips as early as 1929.

Moomintroll was her signature character. Literally.

The lumpy, gently adventurous big-eyed romantic goof began life as a spindly sigil next to her name in her political works. She called him “Snork†and claimed she had designed him in a fit of pique as a child – the ugliest thing a precocious little girl could imagine – as a response to losing an argument about Immanuel Kant with her brother.

The term “Moomin†came from her maternal uncle Einar Hammarsten who attempted to stop her pilfering food when she visited by warning her that a Moomintroll guarded the kitchen, creeping up on trespassers and breathing cold air down their necks. Snork/Moomin filled out, became timidly nicer – if a little clingy and insecure – acting as a placid therapy-tool to counteract the grimness of the post-war world.

The Moomins and the Great Flood was relatively unsuccessful but Jansson persisted, probably as much for her own edification as any other reason, and in 1946 the second book Kometjakten (Comet in Moominland) was published. Many commentators have reckoned the terrifying tale a skilfully compelling allegory of Nuclear destruction.

When it and her third illustrated novel Trollkarlens hatt (1948, Finn Family Moomintroll or occasionally The Happy Moomins) were translated into English in 1952 to great acclaim, it prompted British publishing giant Associated Press to commission a newspaper strip about her seductively sweet and sensibly surreal creations.

Jansson had no misgivings or prejudices about strip cartoons and had already adapted Comet in Moominland for Swedish/Finnish paper Ny Tid.

Mumintrollet och jordens undergäng – Moomintrolls and the End of the World – was a popular feature so Jansson readily accepted the chance to extend her eclectic family across the world.

In 1953 The London Evening News began the first of 21 Moomin strip sagas which promptly captivated readers of all ages. Tove’s involvement in the cartoon feature ended in 1959, a casualty of its own success and a punishing publication schedule. So great was the strain that towards the end she had recruited her brother Lars to help. He took over, continuing the feature until its end in 1975.

Free of the strip Tove returned to painting, writing and her other creative pursuits, generating plays, murals, public art, stage designs, costumes for dramas and ballets, a Moomin opera and another nine Moomin-related picture-books and novels, as well as thirteen books and short-story collections strictly for grown-ups.

Her awards are too numerous to mention but consider this: how many modern artists – let alone comics creators – get their faces on the national currency? She died on June 27th 2001.

Her Moomin comic strip has been collected in seven Scandinavian volumes and the discerning folk at Drawn & Quarterly have translated these into English for your – and especially my – sheer delight and delectation.

This second oversized (312 x 222mm) monochrome hardback compilation commences with ‘Moomin’s Winter Follies’ as the rotund, gracious and deeply considerate young troll has an accident on ice which prompts the family to begin their preparations for the winter’s hibernation.

However after those efforts lead to nothing but petty disaster, boldly unconventional Moomin Pappa decides that tradition isn’t everything and decrees that they shall all stay awake for the icy months ahead…

The family and their many friends however are soon bedevilled by the obnoxiously enthusiastic Mr. Brisk who cajoles the easygoing Moomins to indulge in his abiding passion for winter sports. The results are painful and far from impressive, but the ruggedly athletic Brisk does turn the head of the overly romantic and lonely Mymble…

As usual, the object of her affections is blithely oblivious, caring only for the upcoming Winter Games, but when the beauteous Snorkmaiden also begins to succumb to Brisk’s physical charms Moomin is compelled to take up ski-jumping to win back her attention.

When that goes poorly he is tempted into contemplating murder until cooler heads, his own gentle nature and the onset of spring produces a gentler solution…

Moomins are easygoing free spirits, bohemians untroubled by hidebound domestic mores and societal pressures. Mamma is warm and capable but overly concerned with propriety and appearances whilst Pappa spends most of his time trying to rekindle his adventurous youth or dreaming of fantastic journeys.

However when prideful snobbish Mrs. Fillyjonk moves in next door, her snooty attitudes unfavourably affect the entire family, resulting in the hiring of ‘Moomin Mamma’s Maid’.

The search for a suitable servant results in disruption and discontent before the dour, distressed and doom-obsessed Misabel – along with her direly depressed dog Pimple – begin to further blight the formerly happy household.

Misabel suffers from secrets and a persecution complex and when Fillyjonk goes missing a detective starts hanging around, adding to the general aura of anxiety until Moomin Mamma shakes herself out of her status-induced funk and starts a campaign to cheer up and change the latest additions to her wildly imaginative, but oddly welcoming home…

‘Moomin Builds a House’ sees Mymble’s eccentrically forgetful but fruitful mother come to visit, inflicting her latest batch of wild and wilful youngsters – seventeen, or thereabouts – on the normally compassionate and understanding trolls.

The children are, to put it mildly, little monsters: destructive, practical joking arsonistic hellions who would put the Belles of St. Trinians to shame and to rout…

Soon, impressionable Moomin is driven out of his home and, egged on by the worst of the brood Little My, attempts to build his own house in the woods.

Possessing none of Moomin Pappa’s artisan or craft skills, the lad’s efforts are far from satisfactory but nonetheless his flighty paramour Snorkmaiden soon joins him, intent on making the shaky edifice their romantic hideaway. Sadly, with Little My still around, their best laid plans soon come unstuck…

This utterly incomparable and heartwarming box of graphic delights concludes with a brilliantly satitical salutary romp as ‘Moomin Begins a New Life’, wherein an itinerant thinker enters the valley sharing his secret recipe for “How to be Happyâ€.

The Prophet is remarkably convincing and, seeing how his pronouncements and suggestions have changed the lives of all their friends and neighbours, the graciously impressionable Moomins try to adjust their behaviour to maximise their joy, unaware that they are already as happy and content as anyone can be…

With the entire community blissed out, the well-intentioned Prophet then convinces the constable to release all the folk in jail, allowing mischievous trickster and scofflaw Stinky to resume his prankish shenanigans…

After convincing Moomin Pappa to set up an illicit still producing hard liquor – which incites Snorkmaiden to run off with another young man – Stinky then convinces heartbroken, abandoned Moomin to turn to the dark side by becoming a glamorous highwayman and jewel thief to win her back.

Having spread malice and disorder Stinky’s next stunt is badly misjudged as he invites a puritan, fire-and-brimstone rival philosopher dubbed the Black Prophet to come and save all the sinners…

Thankfully, as the rival Prophets’ war of words escalates Moomin Mamma at last reaches the end of her patience and intervenes…

Wrapping up the Wild Things wonderment is the short essay ‘Tove Jansson: To Live in Peace, Plant Potatoes, and Dream’: a comprehensive biography and commentary by Alisia Grace Chase PhD which celebrates the incredible achievements of this genteel giant of literature.

These are truly magical tales for the young laced with the devastating observation and razor sharp mature wit which enhances and elevates only the greatest kid’s stories into classics of literature. These volumes are an international treasure and no fan of the medium – or biped with even a hint of heart and soul – can afford to be without them.

© 2007 Solo/Bulls. All other material © its creators. All rights reserved.