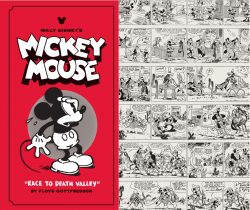

By Floyd Gottfredson & various; Edited by David Gerstein (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-441-2 (HB/Digital edition)

As collaboratively co-created by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, Mickey Mouse was first seen – if not heard – in silent cartoon Plane Crazy. The animated short fared poorly in a May 1928 test screening and was promptly shelved. (Happy technical 95th Anniversary, kid!)

That’s why most people who care cite Steamboat Willie – the fourth Mickey feature to be completed – as the debut of the mascot mouse and co-star and paramour Minnie Mouse, since it was the first to be nationally distributed, as well as the first animated feature with synchronised sound. Its astounding success led to a subsequent and rapid release of fully completed predecessors Plane Crazy, The Gallopin’ Gaucho and The Barn Dance once they too had been given soundtracks. From those timid beginnings grew an immense fantasy empire, but film was not the only way Disney conquered hearts and minds.

With Mickey a certified solid gold sensation, the mighty mouse was considered a hot property and soon invaded America’s most powerful and pervasive entertainment medium: comic strips…

Floyd Gottfredson was a cartooning pathfinder who started out as just another warm body in the Disney Studio animation factory. Happily, he slipped sideways into graphic narrative and evolved into a ground-breaker of pictorial narratives as influential as George Herriman, Winsor McCay and Elzie Segar. Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse entertained millions – if not billions – of eagerly enthralled readers and shaped the very way comics worked.

Via some of the earliest adventure continuities in comics history he took a wild and anarchic animated rodent from slap-stick beginnings and transformed a feisty everyman/mouse underdog into a crimebuster, detective, explorer, lover, aviator or cowboy. Mickey was the quintessential two-fisted hero whenever necessity demanded…

In later years, as tastes – and syndicate policy – changed, Gottfredson steered that self-same wandering warrior into a sedate, gently suburbanised lifestyle, employing crafty sitcom gags suited to a newly middle-class America: a 50-year career generating some of the most engrossing continuities the comics industry has ever enjoyed.

Arthur Floyd Gottfredson was born in 1905 in Kaysville, Utah, one of eight siblings born to a Mormon family of Danish extraction. Injured in a youthful hunting accident, Floyd whiled away a long recuperation drawing and studying cartoon correspondence courses. By the 1920s he had turned professional, selling cartoons and commercial art to local trade magazines and Big City newspaper the Salt Lake City Telegram.

In 1928, he (and wife Mattie) moved to California where, after a shaky start, the doodler found work in April 1929 as an in-betweener with the burgeoning Walt Disney Studios. Just as the Great Depression hit, he was personally asked by Disney to take over the newborn but already ailing Mickey Mouse newspaper strip. Gottfredson would plot, draw and frequently script the strip for the next five decades: an incredible accomplishment by of one of comics’ most gifted exponents.

Veteran animator Ub Iwerks had initiated the print feature with Disney himself contributing, before artist Win Smith was brought in. The nascent strip was plagued with problems and young Gottfredson was only supposed to pitch in until a regular creator could be found.

His first effort saw print on May 5th 1930 (his 25th birthday) and Floyd just kept going for an uninterrupted run over the next half century. On January 17th 1932, Gottfredson crafted the first colour Sunday page, which he also handled until retirement.

In the beginning he did everything, but in 1934 Gottfredson relinquished the scripting role, preferring plotting and illustrating the adventures to playing about with dialogue. Thereafter, collaborating wordsmiths included Ted Osborne, Merrill De Maris, Dick Shaw, Bill Walsh, Roy Williams and Del Connell. At the start and in the manner of a filmic studio system, Floyd briefly used inkers such as Ted Thwaites, Earl Duvall and Al Taliaferro, but by 1943 had taken on full art chores.

This superb archival compendium – part of a magnificently ambitious series collecting the creator’s entire canon – re-presents the initial daily romps, jam-packed with thrills, spills and chills, whacky races, fantastic fights and a glorious superabundance of rapid-fire sight-gags and verbal by-play. The manner by which Mickey became a syndicated star is covered in various articles at the front and back of this sturdy tome devised and edited by truly dedicated, clearly devoted fan David Gerstein.

Under the guise of Setting the Stage the unbridled fun and revelations begin with gaming guru Warren Spector’s appreciative ‘Introduction – The Master of Mickey Epics’ and a fulsome biographical account and appraisal of Gottfredson and Mickey continuities in ‘Of Mouse and Man – 1930-1931: The Early Years’ by historian and educator Thomas Andrae.

The scene-setting concludes with ‘Floyd Gottfredson, The Mickey Mouse Strip and Me – an Appreciation by Floyd Norman’, incorporating some preliminary insights from Gerstein in …An Indebted Valley… before the strip sequences begin in ‘The Adventures: Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse Stories with Editor’s Notes’.

At the start the strip was treated like an animated feature, with diverse hands working under a “director” and each day seen as a full gag with set-up, delivery and a punchline, usually all in service to an umbrella story or theme. Such was the format Gottfredson inherited from Walt Disney for his first full yarn ‘Mickey Mouse in Death Valley’. It ran from April 1st to September 20th 1930 with the job further complicated by an urgent “request” from controlling syndicate King Features. They required that the strip immediately be made more adventure-oriented to compete with the latest trend in comics – action-packed continuities as seen in everything from Wash Tubbs to Tarzan…

Roped in to provide additional art and inking for the raucous, rambunctious rambling saga were Win Smith, Jack King, Roy Nelson & Hardie Gramatky. The tale itself involved a picaresque, frequently deadly journey way out west to save Minnie’s inheritance – a lost mine – from conniving lawyer Sylvester Shyster and his vile and violent crony Peg-Leg Pete.

To foil them Mickey and his aggrieved companion chased across America by every conveyance imaginable, facing every possible peril immortalised by silent movie westerns, melodramas and comedies. In their relentless pursuit they were aided by masked mystery man The Fox…

Next up – after brief preamble ‘Sheiks and Lovers’ – is another lengthy epic, featuring most of the early big screen repertory cast. ‘Mr. Slicker and the Egg Robbers’ (inked by Gottfredson, Gramatky & Earl Duvall and running from September 22nd – December 29th) opens with Mickey building his own decidedly downbeat backyard golf course before being repeatedly and disconcertingly distracted when sleazy sporty type Mr. Slicker starts paying unwelcome attention to Minnie. Well, it’s unwelcome as far as Mickey is concerned…

With cameos from Horace Horsecollar, Clarabelle Cow, goat-horned Mr. Butt and a prototype Goofy who answered – if he felt like it – to the moniker Dippy Dog, the rambunctious shenanigans continue for weeks until the gag-abundant tale resolves into a classic powerplay and landgrab as the nefarious ne’er-do-well is exposed as the fiend attempting to bankrupt Minnie’s family by swiping all the eggs produced on their farm. The swine even seeks to frame Mickey for his misdeed before our hero turns the tables on him…

A flurry of shorter escapades follow: rapid-fire doses of wonder and whimsy including ‘Mickey Mouse Music’ (December 30th 1930 – January 3rd 1931 with art by Duvall), ‘The Picnic’ (January 12th – 17th, Gottfredson inked by Duvall) and ‘Traffic Troubles’ (January 5th – 10th with pencils by Duvall & Gottfredson inks) before Gerstein introduces the next extended storyline with some fondly eloquent ‘Katnippery’…

With story & art by Gottfredson & Duvall, ‘Mickey Mouse Vs. Kat Nipp’ proceeded from January 19th until February 25th 1931, detailing how a brutal feline thug bullies our hero. The sad state of affairs involves tail-abusing in various inspired forms, after which ‘Gallery Feature – …He’s Funny That Way…’ reveals a later Sunday strip appearance for Kat Nipp in a story by Merrill De Maris with Gottfredson pencils & Ted Thwaites inks. The excerpt comes from June 1938.

Gerstein’s introductory thoughts on the next epic – ‘High Society: Reality Show Edition’ – precede the serialised saga of ‘Mickey Mouse, Boxing Champion’. Running February 26th to April 29th by Gottfredson, Duvall & Al Taliaferro, the hilarious episodes relate how ever-jealous Mickey floors a big thug leering at Minnie to become infamous as the guy who knocked out the current heavy lightweight boxing champ.

Ruffhouse Rat’s subsequent attempts at revenge all go hideously awry and before long Mickey is acting as the big lug’s trainer. It’s a disaster and before long the champion suffers an inexorable physical and mental decline. Sadly, that’s when hulking brute Creamo Catnera hits town for a challenge bout. With Ruffhouse refusing to fight, it falls to Mickey to take on the savage contender…

Having accomplished one impossible task, Mickey sets his sights on reintroducing repentant convict Butch into ‘High Society’ (April 30th – May 30th – story & pencils by Gottfredson and inks from Taliaferro). The story was designed to tie-in to a Disney promotional stunt – a giveaway “photograph” of Mickey – and the history and details of the project are covered in ‘Gallery Feature – “Gobs of Good Wishes”’…

‘Mick of All Trades’ introduces the next two extended serial tales, discussing Mickey’s every-mouse nature and willingness to tackle any job like the Taliaferro-inked ‘Circus Roustabout’ which originally ran from June 1st – July 17th. Here a string of animal-based gags is held together by Mickey’s hunt for a cunning thief, after which ‘Pluto the Pup’ takes centre-stage for a 10-day parade of slapstick antics and Gerstein’s ‘Middle-Euro Mouse’ supplies context to the less-savoury and non-PC historical aspects of an epic featuring wandering “gypsies”.

‘Mickey Mouse and the Ransom Plot’ (July 20th – November 7th) follows the star and chums Minnie, Horace and Clarabelle on a travelling vacation to the mountains. Here they fall under the influence of a suspicious band of Roma exhibiting all the worst aspects of thieving and spooky fortune-telling. When Minnie is abducted and payment demanded, Mickey knows just how to deal with the villains…

Essay ‘A Mouse (and a Horse and a Cow) Against the World’ segues into fresh employment horizons for our hero as Gottfredson & Taliaferro test the humorous action potential of ‘Fireman Mickey’ (November 9th – December 5th). Another scintillating cascade of japes, jests and merry melodramas – and taking us from December 7th 1931 to January 9th 1932 in fine style – it offers glimmerings of continuity sub-plotting and supporting character development. These all shade a budding romance under the eaves of ‘Clarabelle’s Boarding House’. Although the chronological cartooning officially concludes here, there’s still a wealth of glorious treats and fascinating revelations in store in The Gottfredson Archives: Essays and Archival Features section that follows.

Contributed by Thomas Andrae, ‘In the Beginning: Ub Iwerks and the Birth of Mickey Mouse’ offers beguiling background and priceless early drawings from the earliest moments, as does Gerstein’s ‘Starting the Strip’ which comes packed with timeless ephemera.

As previously stated, Gottfredson took over a strip already in progress and next – accompanied by covers from European editions of the period – come the strips preceding his accession. Frantic gag-panels (like scenes from an animation storyboard) comprise ‘Lost on a Desert Island’ (January 13th – March 31st 1930, crafted by storyteller Walt and artists Ub Iwerks & Win Smith) are augmented by Gerstein’s ‘The Cartoon Connection’ with additional Italian strips from Giorgio Scudellari in ‘Gallery Feature – “Lost on a Desert Island”’.

Even more text and recovered-art features explore ‘The Cast: Mickey and Minnie’ and ‘Sharing the Spotlight: Walt Disney and Win Smith’ (both by Gerstein) before more international examples illuminate ‘Gottfredson’s World: Mickey Mouse in Death Valley’ whereafter ‘Unlocking the Fox’ traces the filmic antecedents of the hooded stranger, with priceless original art samples in ‘Behind the Scenes: Pencil Mania’.

More contemporaneous European examples from early collections tantalise in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Mr. Slicker and the Egg Robbers’ before Alberto Beccatini & Gerstein’s ‘Sharing the Spotlight: Roy Nelson, Jack King and Hardie Gramatky’ supply information on these lost craftsmen.

Gerstein’s ‘The One-Off Gottfredson Spin-Off’ highlights a forgotten transatlantic strip collaboration with German artist Frank Behmak, whilst ‘Gallery Feature – The Comics Department at Work: Mickey Mouse in Color (- And Black and White)’ covers lost merchandise and production art whilst ‘Gottfredson’s World: Mickey Mouse Vs. Kat Nipp’ and ‘Gottfredson’s World: Mickey Mouse, Boxing Champion’ offer yet more overseas Mouse memorabilia.

‘Sharing the Spotlight: Earl Duvall’ is another fine Gerstein tribute to a forgotten artisan, supplemented by ‘The Cast: Butch’ and ‘Al Taliaferro’, after which ‘The Gottfredson Gang: In “Their Own” Words’ (Gerstein – with texts by Mortimer Franklin & R. M. Finch) reprints contemporary interviews with the 2D stars, garnished with publicity tear-sheets and clippings. This is rounded off by more foreign covers in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Strange Tales of Late 1931’, ‘The Cast: Pluto’ and a stunning Christmas message from the Mouse as per ‘I have it on good authority’, giving Gottfredson himself the last word.

Gottfredson’s influence on not just the Disney canon but sequential graphic narrative itself is inestimable: he was among the first to produce long continuities and “straight” adventures; he pioneered team-ups and invented some of the first “super-villains” in the business.

When Disney killed the continuities in 1955, dictating henceforth strips would only contain one-off gag strips, Floyd adapted seamlessly, working on until retirement in 1975. His last daily appeared on November 15th with the final Sunday published on September 19th 1976.

Like all Disney creators, Gottfredson worked in utter anonymity, but in the 1960s his identity was revealed and the voluble appreciation of his previously unsuspected horde of devotees led to interviews, overviews and public appearances, with effect that subsequent reprinting in books, comics and albums carried a credit for the quiet, reserved master. Floyd Gottfredson died in July 1986.

Thankfully we have these Archives to enjoy and inspire us and hopefully a whole new generation of inveterate tale-tellers…

© 2011 Disney Enterprises, Inc Text of “In the Beginning: Ub Iwerks and the Birth of Mickey Mouse” by Thomas Andrae is © 2011 Thomas Andrae. All contents © 2011 Disney Enterprises unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.