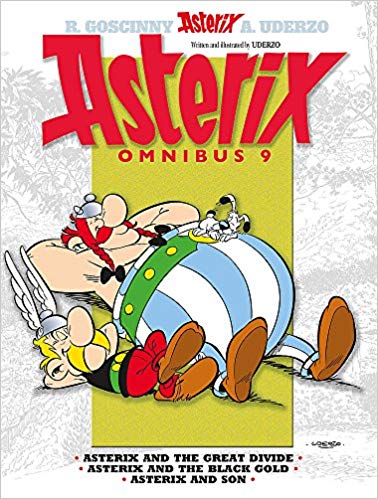

By Uderzo, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Orion Childrens’ Books and others)

ISBNs: 978-1-44400-967-5 (HB), 978-1-44400-966-8 (PB)

Alberto Aleandro Uderzo was born on April 25th 1927 in Fismes, on the Marne, a son of Italian immigrants. Showing great artistic flair as a child reading Mickey Mouse in Le Pétit Parisien, he dreamed of becoming an aircraft mechanic one day. Albert became a French citizen when he was seven and found employment at 13, apprenticed to the Paris Publishing Society, where he learned design, typography, calligraphy and photo retouching.

When WWII broke out, he spent time with farming relatives in Brittany and joined his father’s furniture-making business. Brittany beguiled and fascinated Uderzo: when a location for Asterix’s idyllic village was being mooted the region was the only choice.

During the post-war rebuilding of France, Uderzo returned to Paris and became a successful artist in the country’s revitalised and burgeoning comics industry. His first published work, a pastiche of Aesop’s Fables, appeared in Junior, and in 1945 he was introduced to industry giant Edmond-François Calvo (whose own comics masterpiece The Beast is Dead is long overdue for a new edition…).

Indefatigable Uderzo’s subsequent creations included the indomitable eccentric Clopinard, Belloy, l’Invulnérable, Prince Rollin and Arys Buck. He illustrated Em-Ré-Vil’s novel Flamberge, worked in animation, as a journalist and illustrator for France Dimanche, and created vertical comic strip Le Crime ne Paie pas for France-Soir. In 1950, he illustrated a few episodes of the franchised European version of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Jr. for Bravo!

An inveterate traveller, the prodigy met Rene Goscinny in 1951. Soon fast friends, they decided to work together at the new Paris office of Belgian Publishing giant World Press. Their first collaboration was in November of that year; a feature piece on savoir vivre (how to live right or perhaps gracious living) for women’s weekly Bonnes Soirée, after which an avalanche of splendid strips and serials poured forth.

Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior were created for La Libre Junior and they devised a western starring a native hero who eventually evolved into the delightfully infamous Oumpah-Pah. In 1955 with the formation of Édifrance/Édipresse, Uderzo drew Bill Blanchart for La Libre Junior, replaced Christian Godard on Benjamin et Benjamine, before in 1957 adding Charlier’s Clairette to his portfolio.

The following year he made his debut in Le Journal de Tintin, as Oumpah-Pah finally found a home and a rapturous audience. Uderzo also drew Poussin et Poussif, La Famille Moutonet and La Famille Cokalane.

When Pilote launched in 1959, Uderzo was a major creative force for the new magazine, collaborating with Charlier on Tanguy et Laverdure and launching – with Goscinny – a little something called Astérix le gaulois…

Despite Asterix being a massive hit from the start, Uderzo continued working on Les Aventures de Tanguy et Laverdure, but once the first Roman romp was compiled and collected as Ast̩rix le gaulois in 1961, it became clear that the series would demand most of his time Рespecially as the incredible Goscinny seemed to never require rest or run out of ideas.

By 1967 the strip occupied all Uderzo’s time and attention, so in 1974 the partners formed Idéfix Studios to fully exploit their inimitable creation. When Goscinny passed away three years later, Uderzo had to be convinced to continue the adventures as writer and artist, producing a further ten volumes until 2010 when he retired.

After nearly 15 years as a weekly comic strip subsequently collected into albums, in 1974 the 21st tale (Asterix and Caesar’s Gift) was the first to be published as a complete original album before being serialised. Thereafter each new release was a long-anticipated, eagerly-awaited treat for the strip’s millions of fans…

According to UNESCO’s Index Translationum, Uderzo is the tenth most-often translated French-language author in the world and the third most-translated French language comics author – right after his old mate René Goscinny and the grand master Hergé.

More than 370 million copies of 37 (soon to be 38) Asterix books have sold worldwide, making his joint creators – and their successors Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad – France’s best-selling international authors.

One of the most popular comics features on Earth, the collected chronicles of Asterix the Gaul have been translated into more than 100 languages since his debut, with a wealth of animated and live-action movies, TV series, assorted games, toys, merchandise and even a theme park outside Paris (Parc Astérix, naturellement)…

So what’s it all about?

Like all the best stories the premise works on more than one level: read it as an action-packed comedic saga of sneaky and bullying baddies coming a cropper if you want or as a punfully sly and witty satire for older, wiser heads. We Brits are further blessed by the brilliantly light touch of master translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who played no small part in making the indomitable little Gaul so very palatable to English tongues.

More than half of the canon is set on Uderzo’s beloved Brittany coast, where – circa 50 B.C. – a small village of cantankerous, proudly defiant warriors and their families resist every effort of the mighty Roman Empire to complete the conquest of Gaul. The land has been divided by the conquerors into compliant provinces Celtica, Aquitania and Amorica, but the very tip of the last cited just refuses to be pacified…

The remaining epics occur in various locales throughout the Ancient World, with the Garrulous Gallic Gentlemen visiting every fantastic land and corner of the myriad civilisations that proliferated in that fabled era…

When the heroes were playing at home, the Romans, unable to defeat the last bastion of Gallic insouciance, futilely resorted to a policy of absolute containment. Thus, the little seaside hamlet is permanently hemmed in by the heavily fortified garrisons of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.

The Gauls couldn’t care less: daily defying the world’s greatest military machine simply by going about their everyday affairs, protected by the magic potion of resident druid Getafix and the shrewd wits of the diminutive dynamo and his simplistic, supercharged best friend Obelix…

Firmly established as a global brand and premium French export by the mid-1960s, Asterix continued to grow in quality as Goscinny & Uderzo toiled ever onward, crafting further fabulous sagas; building a stunning legacy of graphic excellence and storytelling gold. Moreover, following the civil unrest and nigh-revolution in French society following the Paris riots of 1968, the tales took on an increasingly acerbic tang of trenchant satire and pithy socio-political commentary…

By the time of the first tale in this omnibus edition was released Goscinny had been gone for three years and Uderzo soldiered on alone…

Asterix and the Great Divide was the 25th volume, released in 1980 as Le Grand Fossé, and in many ways something of a departure and stylistic compromise.

In another Gaulish village, internecine strife is brewing. Political rivals Cleverdix and Majestix have split the sleepy hamlet down the middle, with an election for chief ending in a dead tie. They then make the figurative literal by having a huge trench dug through the centre of town, cutting the tribe in two, with the population resolved into uncompromising Leftists and stubborn Rightists…

It’s a tragedy in many ways, with friends and families split into feuding camps, but the most heartrending separation concerns dashing Histrionix, son of Leftist Cleverdix and his one true love Melodrama, daughter of Majestix. Their warring sires refuse to concede or compromise and that simmering Cold War has frustrated their children’s happiness forever…

The lover’s pleas cannot move either deadlocked party leader and the intolerable situation is further exacerbated by the insidious, coldly calculating advisor to Majestix who secretly eggs on the old warrior for his own purposes.

Wily toady Codfix‘s latest idea is to get their Roman overlords to intervene, installing Majestix as sole ruler by force. In return, Codfix would be given Melodrama in marriage. Of course, that would make him next in line for the ruler’s position. Codfix is both patient and ambitiously far-sighted…

When Melodrama learns of the plan, she immediately informs Histrionix and the prince tells Cleverdix – who knows full well he cannot resist the overwhelming might of the Romans. The former soldier then remembers an old war-buddy who still successfully resists the conquerors. His name was Vitalstatistix…

As Histrionix heroically dashes to the village of Indomitable Gauls – everything he does is heroic – Codfix has gone to the local garrison with his request. Centurion Umbrageous Cumulonimbus, however, has his own problems: discipline is lax and the soldiers are grumbling because of the menial chores they are forced to perform. Codfix has the perfect solution. If the Romans put Rightist Majestix in charge, they could take the pacified Leftists as slaves…

In the meantime, Histronix has returned with Vitalstatistix’ best men. Asterix, Obelix and Getafix the Druid are discussing the matter with Cleverdix when Roman soldiers arrive. Codfix however, has overstepped himself and underestimated the nobility of Majestix…

The doughty Rightist refuses to let any Gaul be enslaved – even political opponents – so the uncaring Romans grab him and his followers instead. Impressed with his rival’s integrity, Cleverdix accepts Asterix’ offer of assistance and our heroes infiltrate the garrison as volunteer slaves using an elixir that revitalises the body but causes a touch of amnesia…

Having fun by exploiting these new Romans’ ignorance of their true identities, the infilitrators feed the imprisoned Gauls soup fortified with the Druid’s strength potion before Asterix and Obelix lead a mass breakout which soon finds the prisoners back in their divided hamlet but no closer to an amicable resolution.

And both sides know that the Romans will soon come, eager for revenge…

Codfix has sensibly stayed with the garrison and found the last of Getafix’ elixir, left behind during the liberation. When he sneaks back into the village, he also discovers a fresh batch of power-potion whipped up in advance of the impending attack… and steals it.

The next day, the Gauls wake to find invaders marching upon them, fortified by the elixir which has erased the punishing memory of their recent defeat, and simultaneously super-charged by power potion.

Left with nothing but Obelix and Gaulish courage, the villagers unite to fight and fall with honour, but are astonished when a bizarre series of transformations wrack the empowered Romans. It takes a long time to become a Druid and apparently the first thing you learn is to never mix potions…

Codfix has used the distraction to kidnap Melodrama. Demanding ransom and safe passage, he has not reckoned on Histrionix’ determination, Asterix’s ingenuity or Obelix’ strength and – after a climactic confrontation involving our perennially luckless Pirates – gets what’s coming to him…

With the Romans routed and Codfix suitably punished, Cleverdix and Majestix settle their differences with a traditional Gaulish duel after which someone else becomes chief of the reunified village. The former divide is transformed into an appropriate symbol of their unity and life goes on happily…

Asterix and the Great Divide was devised by Uderzo as a critique on current affairs and metaphorical attack on the Berlin Wall which had, since 1961, split the city physically, Europe symbolically and the world ideologically. His earnest tale was more dramatic and action-oriented than previous Asterix fare, with the regulars frequently reduced to subordinate roles, but for all that there are still cunning laughs and wry buffoonery in welcome amounts.

Asterix and the Black Gold (L’Odyssée d’Astérix) debuted in 1981 and again saw Asterix and Obelix embarking on a long voyage into the unknown, rife with bold adventure and underpinned by topical lampooning and timeless swingeing satire.

The 26th saga begins with a brace of wild boar demonstrating that they are canny opponents for voracious Obelix. Whenever the gigantic Gaul encounters these particular pigs in his daily hunts, they escape by leading him to the nearest Roman patrol. The only thing Obelix loves more than eating pork is bashing Romans…

Back in Rome, Julius Caesar is livid. He’s just received news that the insufferable, indomitable Gauls are training wild boars to lead Roman patrols into Gaulish ambushes…

The raging ruler’s continued attempts to end the aggravating resistance always fail and in a fit of fury he charges his chief of the Roman Secret Service M.I.VI (geddit?) with ending his galling Gallic grief – or else…

M. Devius Surreptitius has just the man for the job. Dubbelosix is of Gaulish-Roman extraction and has, by persistence and deviousness, qualified as a Druid. He is wily, charming, debonair and comes with a host of cunning hidden gadgets – and he’s also the spitting image of Sean Connery…

Dispatched on a mission to stop the French resisting, Dubbelosix is secretly working with his boss M to supplant Caesar, and also harbours ambitions to rule Rome alone …but first he has to destroy the infernal Gauls. His chance comes almost as soon as he arrives in that little village…

Getafix is in a near-panic. The Druid has been eagerly awaiting the arrival of Phoenician merchant Ekonomikrisis who is bringing a vital ingredient for the magic potion that keeps the Romans at bay. When the ship at last arrives and the peddler apologises for forgetting the fabled rock oil, the highly strung Getafix has a fit and passes out.

Luckily a young Druid dubbed Dubbelosix is passing and, after a minor skirmish with a Roman patrol, accompanies Asterix and Obelix back to their comatose friend…

The spy might be a double agent, but he knows his stuff and soon cures the ailing Getafix, who explains that the generally useless black ooze from the Middle East is vital to the potion: without a fresh supply they are all doomed…

When Asterix and Obelix – and faithful hound Dogmatix, of course – volunteer to obtain some of the crucial rock oil, Dubbelosix insists on accompanying them. But as they commandeer the Phoenician’s ship for the emergency mission, Getafix clandestinely warns Asterix to watch the too-good-to-be-true young Druid…

Expediting matters by selling off Ekonomikrisis’ wares at prices nobody – even Pirates – dare refuse, our heroes make their way to Mesopotamia, unaware that Dubbelosix, using his unique messaging service, has briefed Caesar and M to stop the ship at all costs.

After a succession of military vessels are sent to the bottom of the Mediterranean by the joyfully belligerent Gauls, the Ruler of the World is forced to change tactics and blockade all ports to prevent Asterix and Obelix from disembarking.

With time running out, Ekonomikrisis eventually sneaks the Gauls and Dubbelosix ashore in distant Judea. The trio travel overland to Jerusalem where they are befriended by the locals who have no love for the Romans. The oppressors are always just one step behind the voyagers, though. It is as if someone is telling them every time the questers alter their plans…

After a memorable night in a village called Bethlehem, the Hebrews’ attempt to smuggle the Gauls into Jerusalem is sabotaged by Dubbelosix. However, the Middle Eastern garrisons have never seen fighters like Asterix and Obelix and the doughty heroes escape, leaving the scurrilous double agent behind.

With time running out at home and no word of the fate of their friends, the Gauls are hidden by friendly merchants, and learn that the Romans have seized and burned all the rock oil in the city – and probably the entire region. Their only chance to secure some of the previously worthless black goo is to get it from the source – in Babylon, where it just seeps out of the ground…

Assisted by brave, helpful guide Saul ben Ephishul (a loving visual tribute to Uderzo’s deeply-missed partner René Goscinny, who was Jewish) Asterix and Obelix undertake another perilous journey into the deep desert, frolicking in the Dead Sea and encountering a procession of fanatical tribes all warring on each other for long-forgotten reasons in a savage lampoon of modern Middle East strife…

Eventually, the Gauls become completely lost; waterless and without hope under the scorching sun. However when little Dogmatix starts digging in the sand, the resultant oil gusher provides more than enough to buoy up their hopes and they battle on to rendezvous with Ekonomikrisis for a frantic return to Gaul.

Unfortunately, Dubbelosix has tracked them down again and has one last trick to play…

This return to the style and format of classic collaborations features hilarious comedy set-pieces, thrilling drama and a bitingly gentle assault on the madness of keeping ancient feuds alive, intransigence of religious tensions and the madness of recurring oil crises; lampooning ideologies and dogmas whilst showing how great it is when people can just get along.

Fast, furious and funny-with-a-moral, this is one of the artist/author’s very best efforts and even manages a double-shock ending…

Asterix and Son was released in 1983, the 27th saga and another unconventional step off the well-worn path as it touches on a rather touchy subject…

One particularly fine morning in the Village of Indomitable Gauls, Asterix and Obelix awake to discover someone has left a baby in a basket on their doorstep. Nonplussed and bewildered, they try to care for the infant – much to the horror of the local cows who would be delighted to provide sustenance if milked in a normal manner – but human tongues in the village are beginning to wag…

Things only get worse after the feisty tyke develops a taste for magic potion and somehow keeps finding new supplies of it…

Determined to clear his name and find the real parents, Asterix begins his investigations at the four Roman Garrisons, even as Crismus Cactus, Prefect of Gaul begins a suspiciously sudden emergency census of the local villages…

Hyper-charged on potion, the baby keeps getting out and following Asterix and Obelix, who discover that the Romans seem to be looking for one child in particular…

After a painful encounter with our heroes, Crismus Cactus retires to his villa where a VIP from Rome is waiting. Marcus Junius Brutus is Caesar’s adopted son and is most insistent that the mystery baby is found and turned over to him – even if he has to raze all Gaul to achieve his aim…

The infant in question is still causing trouble for the villagers and Brutus marshals an army near the isolated hamlet, successfully confirming the child’s location with a rather inept spy. The kid’s treatment of the intruder prompts Asterix to seek out a nanny, but as the village women are still suspicious and condemnatory, he hires a rather unsavoury stranger named Aspidistra for the task…

This provokes even more vicious tongue-wagging amongst the women, who assume the worst of both her and Asterix. Inexplicably, nobody notices the ferocious childminder’s astonishing resemblance to the Prefect of Gaul…

Unfortunately, once Crismus has successfully infiltrated the village he can’t get out again, and spends a punishing time amusing the infant horror until his nerve breaks. Drained of patience, Brutus then attacks with the full might of Rome, torching the village and bombarding it with catapults.

As the men tank up on potion and counterattack, the village women head for the beach. Sadly, Brutus is willing to sacrifice his entire army, and is waiting to grab the baby…

Once the Roman Legions are crushed, Asterix and Obelix return and discover what has occurred. Filled with rage, they set off in deadly pursuit and save the child just in time for his real mother and father to arrive. Two of the most powerful people in the world, they are extremely angry with somebody…

Laced with a dark and savage core, this rollicking rollercoaster ride combines tragedy with outrageous slapstick, transforming historical facts into a compelling comedy-drama that is both delightful and genuinely scary in places…

Stuffed with sly pokes and good-natured joshing, featuring famous caricatures to tease older readers whilst the raucous, bombastic, bellicose hi-jinks and riotous action astounds and bemuses the younger set, these tales celebrate the illustrative ability of Uderzo, confirming his potion-powered paragon of Gallic Pride to be a true national and cultural treasure.

If you still haven’t experienced this sublime slice of French polish and graphic élan, it’s never too late…

© 1980-1983 Goscinny/Uderzo. Revised English translation © 2002 Hachette. All rights reserved.