By Jack Oleck, illustrated by Berni Wrightson (Warner Paperback Library)

ISBN: 0-446-75226-6- 095

When superheroes entered their second decline in the early 1970s, four of the six surviving newsstand comicbook companies (Archie, Charlton, DC, Gold Key, Harvey and Marvel) relied increasingly on horror and suspense anthologies to bolster their flagging sales. Even wholesome Archie briefly produced Red Circle Sorcery/Chillers comics and their teen-comedy core moved gently into tales of witchcraft, mystery and imagination.

DC’s first generation of mystery titles had followed the end of the first Heroic Age when most comicbook publishers of the era began releasing crime, romance and horror genre anthologies to recapture the older readership which was drifting away to other mass-market entertainments like television and the movies.

As National Comics in 1951, the company bowed to the inevitable and launched a comparatively straight-laced anthology – which nevertheless became one of their longest-running and most influential titles – with the December 1951/January 1952 launch of The House of Mystery.

When a hysterical censorship scandal led to witch-hunting hearings attacking comicbooks and newspaper strips (feel free to type Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, April-June 1954 into your search engine at any time) the industry panicked, adopting a castrating straitjacket of stringent self-regulatory rules and admonitions.

Even though mystery/suspense titles produced under the aegis of the Comics Code Authority were sanitised, anodyne affairs in terms of Shock and Gore, the appetite for suspense was still high, and in 1956 National introduced sister titles Tales of the Unexpected and House of Secrets.

Supernatural thrillers and spooky monster stories were dialled back into marvellously illustrated, genteel, rationalistic fantasy-adventure vehicles which nonetheless dominated the market until the 1960s when the super-hero returned in force – having begun a renaissance after Julius Schwartz reintroduced the Flash in Showcase #4, 1956.

Green Lantern, Hawkman, the Atom and a host of other costumed cavorters generated a gaudy global bubble of masked myrmidons which even forced the dedicated anthology suspense titles to transform into super-character split-books with Martian Manhunter and Dial H for Hero in House of Mystery and Mark Merlin – later Prince Ra-Man – sharing space with anti-hero Eclipso in House of Secrets.

When the caped crusader craziness peaked and popped, Secrets was one of the first casualties, folding with the September-October 1966 issue. House of Mystery carried on with its eccentric costumed cohort until #173 and Tales of the Unexpected to #104.

However nothing combats censorship better than falling profits, and at the end of the 1960s the superhero boom busted again, with many titles gone and some of the industry’s most prestigious series circling the drain too…

This real-world Crisis led to the surviving publishers of the field agreeing to loosen their self-imposed restraints against crime and horror comics. Nobody much cared about gangster titles at the time, but as the liberalisation coincided with another bump in public interest in all aspects of the Great Unknown, the resurrection of scary stories was a foregone conclusion and obvious “no-brainer.â€

Thus with absolutely no fanfare at all House of Mystery and Unexpected switched to scary stories and House of Secrets rose again with issue #81, (cover-dated August-September 1969); retasked and retooled to cater to a seemingly insatiable public appetite for tales of mystery, horror and imagination … Before long a battalion of supernatural suspense titles dominated DC and other companies’ publishing schedules again.

Simultaneously and contiguously, there had been a revolution in popular fiction during the 1950s with a huge expansion of affordable paperback books, driving companies to develop extensive genre niche-markets, such as war, western, romance, science-fiction, fantasy and horror…

Always hungry for more product for their cheap ubiquitous lines, many old novels and short stories collections were republished, introducing new generations to fantastic pulp authors like Robert E. Howard, Otis Adelbert Kline, H.P. Lovecraft, August Derleth and many others.

In 1955, spurred on by the huge parallel success of cartoon and gag book collections, Bill Gaines began releasing paperback compendiums culling the best strips and features from his landmark humour magazine Mad and thus comics’ Silver Age was mirrored in popular publishing by an insatiable hunger for escapist fantasy fiction.

In 1964 Bantam Books began reprinting the earliest pulp adventures of Doc Savage, triggering a revival of pulp prose superheroes, and seemed the ideal partner when Marvel began a short-lived attempt to “novelise†their comicbook stable with The Avengers Battle the Earth-Wrecker and Captain America in the Great Gold Steal.

Although growing commercially by leaps and bounds, Marvel in the early 1960s was still hampered by a crippling distribution deal limiting the company to 16 titles (which would curtail their output until 1968), so each new comicbook had to fill the revenue-generating slot (however small) of an existing title. Even though the costumed characters were selling well, each new title would limit the company’s breadth of genres (horror, western, war, etc) and comics were still a very broad field at that time. It was putting a lot of eggs in one basket and superheroes had failed twice before for Marvel.

As Stan Lee cautiously replaced a spectrum of genre titles and specialised in superheroes, a most fortunate event occurred with the advent of the Batman TV show in January 1966. Almost overnight the world went costumed-hero crazy and many publishers repackaged their old comics stories in cheap and cheerful, digest-sized monochrome paperbacks. Archie, Tower, Marvel and DC all released such reformatted strip books and the latter two carried on their attempts to legitimise their output by getting them into actual bookshops to this day.

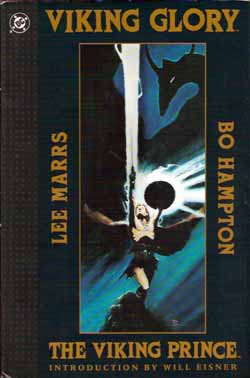

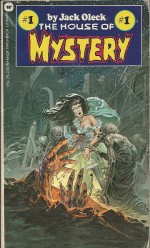

Released in 1973, when the horror boom was at its peak, Tales from The House of Mystery was another attempt to breach the bookshop barrier. A prose anthology by veteran comics scripter Jack Oleck, the compendium adapted and modified, for a presumed older audience, eight short scary stories from the comics, each magnificently illustrated by DC’s top terror artist “Berni†Wrightson, who also provided a moodily evocative frontispiece starring the comic’s macabre host Cain and the stunning painted cover above.

The wry, dry shock-ending mini-epics begin with ‘Chamber of Horrors’ wherein a violently paranoid young man gets the notion that the newcomers in town are a family of vampires, after which ‘Nightmare’ reveals the uncanny fate of an obnoxious American vacationer who was determined to ruin a day-trip to Stonehenge for all those gullible over-imaginative fools on the tour bus…

‘Collector’s Item’ related how two old friends sharing a passion for coin collecting met a ghastly fate after squabbling over some particularly impressive specimens from ancient Judea, and ‘Born Loser’ proved that for some poor schmucks even magic wasn’t enough to escape a shrewish wife and the consequences of murder…

‘Tomorrow, the World’ detailed the efforts of a concerned psychiatrist who was unable to shake the convictions of his hopeless patient that a coven of witches and warlocks was about to conquer the world for Satan, whilst the bittersweet romance of ‘The Haunting’ revealed a shocking truth about the house acquired by devoted newlyweds Joel and Peggy.

Voodoo and reincarnation proved the lie to the maxim ‘You Only Die Once’ after a French plantation owner thought he had gotten away with murdering his coldly disdainful wife, and this brief box of dark delights ends on a savagely ironic and even cruel note as well-meaning social workers and doctors cure a desolated lame orphan of his foolish belief in a happy fantasy land by an ‘Act of Grace’…

By today’s standards this octet of occult thrillers might seem a little tame or dated, and the experiment clearly had no lasting effect on either comics or book consumers, but this little oddity is still a fascinating experiment that will delight comics completists, arch-nostalgics and fantasy fans alike…

© 1973 National Periodical Publications, Inc. All rights reserved.