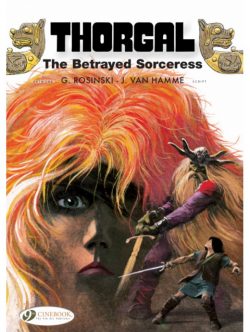

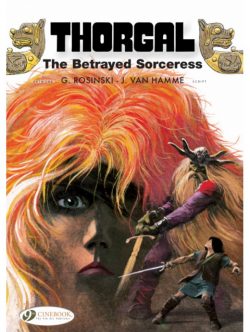

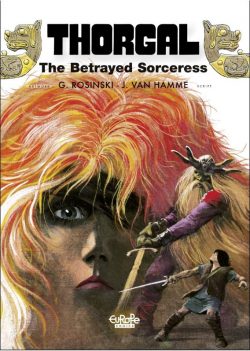

By Rosiński & Van Hamme, translated by Jerome Saincantin (Europe Comics/Cinebook)

No ISBN (Europe Comics digital-only edition)

ISBN: 978-1-84918-443-4 (Cinebook PB Album)

One of the very best and most celebrated fantasy adventure series of all time, Thorgal accomplishes the seemingly impossible: pleasing critics and selling in vast quantities.

The prototypical Game of Thrones saga debuted in iconic weekly Le Journal de Tintin in 1977 with album compilations beginning three years later. A far-reaching and expansive generational saga, it has won a monolithic international following in fourteen languages and dozens of countries, generating numerous spin-off series, and thus naturally offers a strong presence in the field of global gaming.

In story-terms, Thorgal offers the best of all weird worlds, with an ostensibly historical milieu of bold Viking adventure seamlessly incorporating science fiction elements, dire magic, horrendous beasts, social satire, political intrigue, soap opera, Atlantean mystique and mythically mystical literary standbys such as gods, monsters and devils.

Created by Belgian writer Jean Van Hamme (Domino, XIII, Largo Winch, Blake and Mortimer) and Polish illustrator Grzegorz RosiÅ„ski (Kapitan Å»bik, Pilot ÅšmigÅ‚owca, Hans, The Revenge of Count Skarbek), the feature grew unstoppably over decades with the creative duo completing 29 albums between 1980 and 2006 when Van Hamme moved on. Thereafter the scripting duties fell to Yves Sente who collaborated on a further five collections until 2013 when Xavier Dorison wrote one before Yann became chief scribe. In 2019, he and RosiÅ„ski released the 37th epic-album L’Emite de Skellingar.

By the time Van Hamme departed, the canon had grown to cover not only the life of the titular hero and his son Jolan, but also other indomitable family members through a number of spin-off series (Kriss de Valnor, Louve, La Jeunesse de Thorgal) all clustered under the umbrella title Les Mondes de Thorgal – with all eventually winning their own series of solo albums.

In 1985, US publisher Donning released a brief but superb series of oversized hardcover translations, but Thorgal never really found an English-speaking audience until Cinebook began its own iteration in 2007.

The original Belgian series meandered back and forth through the hero’s life and Cinebook’s translated run began with the 7th and 8th albums combined in a double-length premiere edition. By that time the saga of wandering enigma Thorgal Aegirsson had properly gelled, but there were a few books before then, with the hero still finding his literary and graphic feet…

What you’ll learn from later volumes: Thorgal was recovered as a baby from a ferocious storm and raised by Northern Viking chief Leif Haraldson. Nobody could possibly know the fortunate foundling had survived a stellar incident which destroyed a starship full of super-scientific aliens…

Growing to manhood, the strange boy was eventually forced out of his adopted land by ambitious usurper Gandalf the Mad who feared the young warrior threatened his own claim to the throne.

For his entire childhood Thorgal had been inseparable from Gandalf’s daughter Aaricia and, as soon as they were able, they fled together from the poisonous atmosphere to live free from her father’s lethal jealousy and obsessive terror of losing his throne…

Danger was always close but after many appalling hardships, the lovers and their new son finally found a measure of cautious tranquillity by occupying a small island where they could thrive in safety… or so they thought…

Here, however, in these harder-hitting, initial escapades from 1980, the largely unexplained and formulaic Viking warrior is simply a hero in search of a cause. La Magicienne Trahie becomes eponymous debut book The Betrayed Sorceress, opening with a full-grown Thorgal tortured and left to die of exposure and drowning by arch enemy Gandalf.

He is fortuitously rescued by a red-haired woman who demands he work in her service for a year…

Accompanied by a loyal wild wolf, formidable mystic matron Slive is consumed with a hunger for vengeance and orders her reluctant vassal to undertake an arduous quest and great battles to retrieve a hidden casket and its mystical contents. Only after succeeding, does the warrior discover that the target of her ire is Gandalf…

The complex scheme almost succeeds but the witch’s plans eventually lead to bloodshed, calamity, an unsuspected connection to the hero’s beloved Aaricia and the exposure of long-hidden secrets.

As the final clash climaxes, Gandalf is near death and the lovers witness the sorceress’ last voyage into the coldest regions on Earth in a dragonship made of ice…

Follow-up exploit ‘Almost Paradise’ continues the saga and completes the first volume with Thorgal living again amongst Gandalf’s band, but only on sufferance and in constant daily hardship.

Here, a lone ride through winter snows leads to his being hunted by ravening wolves before plummeting into a fantastic time-lost and timeless enclave at the bottom of an icy crevasse. In that tropical Eden he finds a trio of mysterious maidens. Two vie for his attention and argue the seductive benefits of eternal life in a vast garden free of want and danger, but youngest girl Skadia secretly craves the freedom of the outside world and is willing to lead the homesick warrior into horrendous peril to achieve her ends. Desperate to return to his true love, Thorgal escapes with the third immortal, suffering a nightmare journey back to the real world, but not without paying a painful price…

Second collected album L’lle des Mers gelées is also included here as The Island of the Frozen Seas, and begins in spring as Aaricia readies herself to wed Thorgal and leave Gandalf’s lands forever. Those dreams are suddenly shattered when a brace of giant eagles fly down and snatch her away. Soon the entire band of warriors are pursuing in their Drakkars (dragonships), heading ever northwards…

The chase leads to fractious moments aboard ship and imminent mutiny is only forestalled when the Vikings encounter a fantastic vessel that moves without oars or sails. Despite valiant resistance, the barbarians are soon all captives beside Aaricia. All, that is, save for Thorgal and future brother-in-law Bjorn Gandalfson who escaped capture by taking to a lifeboat…

At the top of the world, they meet strange tribes-folk perfectly adapted to arctic existence and Thorgal continues his hunt for his intended bride, meeting and defeating her abductor, discovering an incredible secret citadel and uncovering an incredible story about his long-occluded origins before he can bring his beloved back home to her people…

Although lacking the humour of later tales these works in progress are fierce, inventive and phenomenally gripping: cunningly crafted, astonishingly addictive episodes gradually building towards a fully-realised universe of wonder and imagination whilst offering insight into the character of a true, if exceedingly unwilling hero.

Thorgal is every action fan’s ideal dream of unending adventure. What fanatical fantasy aficionado could possibly resist such barbaric blandishments?

This Europe Comics volume is a digital-only edition from the pan-continental collective imprint which collaborates to bring a wealth of fresh and classic material to English speaking fans. Many of their selections are picked up by established print publishers such as Top Shelf or Cinebook. In fact, this volume will be added to Cinebook’s stable of titles at the end of the year, under special enumeration as Thorgal volume 00: The Betrayed Sorceress, so if you’re already a fan you can wait until then to add the book to your collection. If you can’t wait, though, the past awaits you, only a few keystrokes away…

© Editions du Lombard (Dargaud-Lombard s.a.) 1980 Rosiński & Van Hamme. English translation © 2018 Cinebook Ltd.

Thorgal volume 00: The Betrayed Sorceress is scheduled for a November 2019 release by Cinebook.