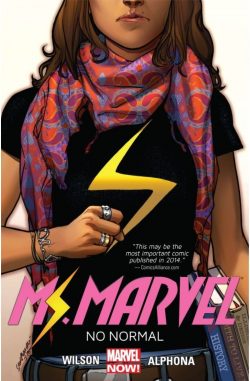

By G. Willow Wilson, Adrian Alphona, Ian Herring, VC’s Joe Caramagna & various (MARVEL)

ISBN: 978-0-7851-9021-9 (TPB/Digital edition)

In a comic book title, the soubriquet “Marvel” carries a lot of baggage and clout, and has been attached to a wide number of vastly differing characters over many decades. In 2014, it was inherited by comics’ first mainstream first rank Muslim superhero, albeit employing the third iteration of pre-existing designation Ms. Marvel.

Career soldier, former spy and occasional journalist Carol Danvers – who rivals Henry Pym in number of secret identities, having been Binary, Warbird, Ms. Marvel again and ultimately Captain Marvel – originated the role when her Kree-based abilities first manifested. She experienced a turbulent superhero career and was lost in space when Sharon Ventura became the second, unrelated Ms. Marvel. She gained her powers from the villainous Power Broker, and after briefly joining the Fantastic Four, was mutated by cosmic ray exposure into a She-Thing…

Debuting in a sly cameo in Captain Marvel (volume 7 #14, September 2013) and bolstered by a subsequent teaser in #17, Kamala Khan was the third to use the codename. She properly launched in full fight mode in a tantalising short episode (All-New MarvelNow! Point One #1) chronologically set just after her origin and opening exploit.

That aforementioned origin saga unfolded in #1-5 of Ms. Marvel (volume 3), and forms the majority of this first collection of light-hearted all-ages adventure originally published between cover-dates April-August 2014.

Collaboratively conceived by editors Sana Amanat and Stephen Wacker, the character was realised by writer and journalist G. Willow Wilson, (Mystic: The Tenth Apprentice, Cairo, Air, The Butterfly Mosque, Alif the Unseen) and illustrator Alphonse Alphona (Uncanny X-Force, Captain Britain and MI13, Runaways) with additional design input from Jamie McKelvie (Suburban Glamour, Long Hot Summer, Young Avengers, The Wicked + the Divine, Phonogram, Rue Britannia), who jointly recast the classic origin and setting of Spider-Man for a new age. The entire epic was coloured by Ian Herring and lettered by VC’s Joe Caramagna.

Kamala Khan is a teenager living in Jersey City. Just across the Hudson river lies Manhattan, and the superhero geek frequently enjoys a distant ringside seat to the constant wonders that occur there.

As a Pakistani American growing up Muslim she has her share of daily dramas at Coles Academic High School and elsewhere, but life is generally pretty good. She has good friends like Bruno and Kiki (Nakia), petty annoyances like golden girl Zoe Zimmer and jock Josh or even her loving family. They don’t really understand her obsession with computers, social media and especially with making superhero fan fiction – especially as Kamala is getting older now and needs to start thinking seriously about her future…

Miss Khan’s stolid suppressed status quo abruptly changes in ‘Meta Morphosis’ on the night she breaks a parental embargo and sneaks out to attend a party. Any potential enjoyment is marred by guilt, apprehension and Zoe and Josh, but the real shock comes on the way home when the city is enveloped in a strange fog that causes Kamala to collapse.

During earlier mega-crossover blockbuster Infinity, mad Titan Thanos invaded Earth and clashed with the Inhumans and battled their King Black Bolt to a standstill. As a last resort the embattled sovereign crashed sky-floating city Attilan onto New York and into the Hudson, releasing the Hidden People’s mutagenic Terrigen Mist into the atmosphere.

As it traversed the globe, the gas cloud triggered mutation in millions, proving that Human and Inhuman were not different species and that dormant Inhuman genes reposed everywhere, unsuspected by humankind. All those susceptible to the contaminant either died or metamorphosed into new beings via body-altering cocoons…

Attilan’s crash happened mere hours before and now Kamala is unconscious on a Jersey City street, wracked by bizarre hallucinations of the Avengers and particularly her absolute favourite hero Carol Danvers…

On awakening, she has to smash her way out of a strange shell. When the mists and dust clear Khan is astounded to see she is no longer a “little brown girl” but big, blonde, busty and white. In fact, she looks exactly like the original Ms. Marvel…

In ‘All Mankind’ while experimenting – and puking – Kamala realises she is constantly shapeshifting and body-morphing, but her shock and terror recede after seeing Zoe in danger. Without thinking, Kamala responds to save the Mean Girl, albeit in a manner everybody thinks pretty gross…

Fed up with adventure, Kamala heads home, and is relieved to somehow revert to normal while climbing in her bedroom window. Sadly, ultra-conservative older brother Aamir and her parents are waiting…

‘Side Entrance’ sees Zoe milking her celebrity moment as the media descend on Jersey and Kamala frantically researches her powers – with disastrous results. Desperate to find some way to control them she is spiralling until Bruno comes to her rescue by being held up at his afterschool job. Once again leaping into action as “Carol Danvers”, Kamala learns it’s not that easy a career, after being shot and reverting to her natural form in ‘Past Curfew’…

With a certified genius like Bruno on board, Kamala finally understands what she can do and devises her own costume and alter ego, just as the city is targeted by a genuine – but so weird – supervillain, leading the new Ms. Marvel into the wilds to hunt down an exploitative mastermind running troubled teens as his soldiers.

Brimming with confidence, the neophyte hero is unprepared for the deadly mechanical monsters of The Inventor, a brutal showdown with that invisible crook’s gang or the even worse trial of keeping secrets from her increasingly concerned and bewildered family in closing chapter ‘Urban Legend’…

The initial story arc won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story – the first of many glittering critical acknowledgements – and is followed here by that aforementioned teaser tale from All-New MarvelNow! Point One #1.

Crafted by Wilson, Aphona, Herring & Caramagna, ‘Garden State of Mind’ finds the hero diverted by a marauding trash monster-bot and late for a major family social gathering…

And thus began a meteoric rise for the new hero. Kamala Khan would steal hearts and minds, become a shining example and become a major player in monumental publishing events such as Last Days, Secret Wars, Secret Empire, Civil War II, Generations and Outlawed, whilst joining or leading teams like the All-New All-Different Avengers, Champions, and Secret Warriors and inheriting the lead role in a revived Marvel Team-Up title.

Her role as positive role model cannot be overstated – how many female or Muslim superheroes can you think of, or have ever had their own American TV series?

That success is completely due to the comics stories which perfectly marry action and drama to powerfully engaging view of home life, stuffed to the brim with humour and happy moments, rather than the relentless bleakness of so many superhero sagas.

Colour plays a powerful part in telling these tales, subtly supplementing the ostensibly cartoonish art of Adrian Alphona into suitably tense dramatic fare without ever losing the vivacity and charm of the comedic undertones, so especial kudos to Ian Herring for his impressive and sensitive efforts here…

Similar congratulations to letterer Joe Caramagna for handling a rather dialogue-heavy script (absolutely necessary to capture the brilliant interplay and byplay of the teens and parental generation packing G. Willow Wilson’s extremely engaging and beguiling script).

Wrapping up this volume is a covers & variant gallery by Sara Pichelli & Justin Ponsor, McKelvie & Matthew Wilson, Salvador Larocca & Laura Martin, Arthur Adams & Peter Steigerwald, Jorge Molina, Annie Wu and a fascinating look at Alphona’s ‘Sketchbook’ of character designs and ‘inks to color process’.

Still fresh, funny, thrill-drenched and utterly absorbing, the saga of this Ms. Marvel is something you need to see over and over again.

© 2017 Marvel Characters Inc. All rights reserved.