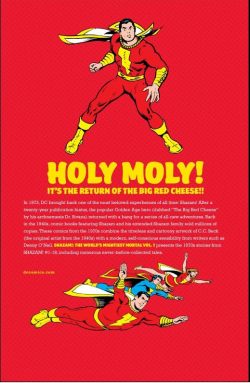

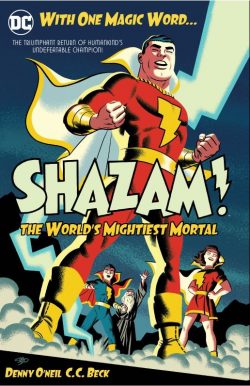

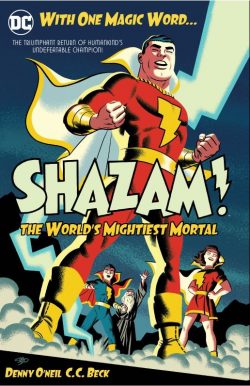

By Denny O’Neil, Elliot S. Maggin, E. Nelson Bridwell, C.C. Beck, Kurt Schaffenberger, Dave Cockrum, Bob Oksner, Dick Giordano & various (DC)

ISBN: 978-1-4012-8839-6 (HB)

One of the most venerated and loved characters in American comics was created by Bill Parker and Charles Clarence Beck as part of the wave of opportunistic creativity that followed the successful launch of Superman in 1938. Although there were many similarities in the early years, the Fawcett character moved swiftly and solidly into the area of light entertainment and even broad comedy, whilst as the 1940s progressed the Man of Steel increasingly left whimsy behind in favour of action and drama.

Homeless orphan and good kid Billy Batson is selected by an ancient wizard to battle injustice and subsequently granted the powers of six gods and mythical heroes. By speaking aloud the wizard’s name – itself an acronym for the six patrons Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles and Mercury – he can transform from scrawny boy to brawny (adult) hero Captain Marvel.

At the height of his popularity Captain Marvel hugely outsold Superman and was even published twice a month, but as the decade progressed and tastes changed sales slowed, and an infamous court case begun in 1941 by National Comics citing copyright infringement was settled. Like many other superheroes the “Big Red Cheese†disappeared, becoming a fond memory for older fans. A big syndication success, he was missed all over the world…

In Britain, where an English reprint line had run for many years, creator/publisher Mick Anglo had an avid audience and no product, and transformed Captain Marvel into atomic age hero Marvelman, continuing to thrill readers into the early 1960s.

As America lived through another superhero boom-and-bust, the 1970s dawned with a shrinking industry and wide variety of comics genres servicing a base that was increasingly founded on collectors and fans rather than casual or impulse buyers. National – now DC – Comics needed sales and were prepared to look for them in unusual places.

After the court settlement with Fawcett in 1953 they had secured the rights to Captain Marvel and his spin-off Family. Now and though the name itself had been taken up by Marvel Comics (via a circuitous and quirky robotic character published by Carl Burgos and M.F. Publications in 1967), the publishing monolith decided to tap into that discriminating if aging fanbase.

In 1973, riding a wave of national nostalgia on TV and in the movies, DC brought back the entire beloved cast of the Captain Marvel crew in their own kinder, weirder universe. To circumvent the intellectual property clash, they named the new title Shazam! (‘With One Magic Word…’): the memorable trigger phrase used by myriad Marvels to transform to and from mortal form and a word that had already entered the American language due to the success of the franchise the first time around.

Now the latest star of film and TV is back in print in this stylish Hardback and digital compendium, collecting the first 18 issues (spanning February 1973 – May/June1975) of a glorious revival. It’s by rapturous and informative introduction With One Magic Word… by Jerry Ordway, writer and artist of latter day reinvention The Power of Shazam!

Back in 1972, the company tapped editor Julie Schwartz – instigator of the Silver Age of Comics and the go-to guy for hero revivals – to steer the project. He teamed top scripter Denny O’Neil with original artist C.C. Beck for the initial re-introductory story. ‘…In the Beginning…’

Delivered in grand old self-referential style, the engaging yarn reprised the classic origin after which ‘The World’s Wickedest Plan’ relates how the entire cast were trapped in a timeless “Suspendium†trap for twenty years after their arch-foes the Sivana family (Doctor Thaddeus Bodog Sivana and his vile but equally brilliant children Georgia and Thaddeus Jr.) attacked them all at a public awards ceremony.

Two decades later, they were all freed, baddies included, to restart their lives. That first issue also included a text-feature/score-card by devotee E. Nelson Bridwell to bring new and old readers up to speed, and ‘Shazam & Son: The Story of the World’s Mightiest Mortal’ is included here to again bring new readers up to super speed.

With issue #2, a format of two stories per issue was instigated. ‘The Astonishing Arch Enemy’ heralds the return of super-intelligent Venusian worm Mr. Mind and a running gag about how strange people in the 1970s are. Written by Elliot Maggin, the second tale introduces eerily irresistible, scrupulously honest Sunny Sparkle who lives awash in the generosity of others who can’t resist giving stuff to ‘The Nicest Guy in the World’. Once again, the fun is counterpointed by a Bridwell text feature listing the many heroes sharing the powers of the gods in ‘Shazam and Family’.

For #3, O’Neil wrote ‘A Switch in Time’ wherein scrofulous underage magician Shagg Nasté disrupts the puny-boy-to-super-adult gimmick for young Billy, whilst Maggin & Beck craft a wry spy tale of daffy inventors in ‘The Wizard of Phonograph Hill’. Next issue evil Captain Marvel analogue ‘Ibac the Cursed’ disastrously re-emerged, courtesy of O’Neil & Beck, with Maggin again opting for a human-interest yarn in ‘The Mirrors that Predicted the Future’.

In the ’70s economics dictated costs in comics be cut whenever possible so there was really no choice about filling pages with reprints, which had been an addition from the start. A huge benefit, however, was that those stories were unknown to the general readership and of a very high standard. Although not included in this volume, I mention them simply because they kept the page-count of most issues to around fifteen pages of new material per month (Shazam! was actually published eight times a year so the savings were even greater). Hopefully DC will get around to reprinting the Fawcett stories too – perhaps in the same format as their excellent Batman, Wonder Woman and Superman Golden Age collections…

Maggin took the lead slot with #5’s ‘The Man who Wasn’t’ (a potentially offensive tale of leprechauns with a rather heavy-handed racial stereotype as the magical foe) as well as a back-up which sees the return of Sunny Sparkle. Here, his obnoxious cousin Rowdy briefly becomes ‘The World’s Toughest Guy!’

O’Neil returned in #6, as did Sivana in time bending tale ‘Better Late than Never!’ whilst Maggin reintroduced a 1940’s boy-genius in the charming ‘Dexter Knox and his Electric Grandmother’. The following issue, loquacious science experiment Tawky Tawny took centre-stage in O’Neil’s ‘The Troubles of the Talking Tiger’ before uber-fan and wonderful guy E. Nelson Bridwell finally got to write a script with the delightfully zany and clever ‘What’s in a Name? Doomsday!

Shazam! #8 was the first of many 100-Page Spectaculars stuffed with great Golden Age reprints, but as such it’s only represented here by the C.C. Beck cover, whilst normal-sized #9 provides us with O’Neil’s ‘Worms of the World Unite’ – another clash with scurrilous dictator Mr. Mind – and the first solo adventure of Captain Marvel Jr. in over twenty years.

‘The Mystery of the Missing Newsstand! is an action-heavy romp and fine tribute to the works of early Fawcett mainstay (and Flash Gordon maestro Mac Raboy); written by Maggin and illustrated by young Dave Cockrum. It is truly lovely to look upon. A third original story completes the issue and Maggin & Beck clearly had heaps of fun on ‘The Day Captain Marvel Went Ape!’ when a mystic jewel deflects Shazam’s magic lightning into a chimpanzee.

Beck, notoriously opinionated, had been unhappy with the stories he was being asked to draw and left the series with #10. He was a supremely understated draughtsman with a canny eye for caricature and gag-timing, and his departure took away some of that indefinable charm. Many other gifted artists continued the strip but a certain kind of magic left the strip with him. He wasn’t even the lead or cover artist on the issue.

Bob Oksner & Vince Colletta illustrated Maggin’s mediocre flying saucer yarn ‘Invasion of the Salad Men’, but happily, Mary Marvel’s solo debut ‘The Thanksgiving Thieves’ is a much better effort with Bridwell’s script handled by Oksner alone (if ever an artist should ink himself it was this superb stylist). Beck bowed out with Bridwell’s ‘The Prize Catch of the Year’ which featured the reappearance of formidable octogenarian villainess Aunt Minerva – one of the most innovative rogues of the Golden Age and here again on the prowl for a new husband…

Issue #11 kicks off with ‘The World’s Mightiest Dessert!’ (Bridwell, Oksner & Colletta) wherein a new sweet treat goes berserk, but the real gem of this comic is ‘The Incredible Cape-Man’. Written by Maggin it saw the long-awaited return of Kurt Schaffenberger, a brilliant and highly accomplished artist who, by his own admission, considered drawing Captain Marvel the best of all possible jobs.

He began his career at Fawcett before moving to DC, ACG and others when the company folded. When the Big Red Cheese returned, his resumption of the art-chores was inevitable. In this tale of a mail man who becomes a Mystery Man, the art positively glows with joyous enthusiasm. This end-of-year issue then concludes with a good old-fashioned Yule yarn featuring the entire extended cast in Maggin & Schaffenberger’s ‘The Year Without a Christmas!’, with our heroes again clashing with the wicked Sivana clan to save the season.

The 12th issue was another 100-Page Spectacular but included 3 all-new stories: modern-day Midas menace ‘The Golden Plague’ (Bridwell & Oksner); another glorious Captain Marvel Jr. adventure ‘The Longest Block in the World!’ (Maggin & Dick Giordano), and cheerfully daft Kung Fu spoof ‘Mighty Master of the Martial Arts!’ by Maggin, Oksner & Colletta. Also included are clip-art features detailing the boy hero’s heroic heritage in ‘Billy Batson’s Family Album’ and his divine sponsors in ‘The Shazam Gods and Heroes’.

The next six issues retained this same format, combining around 20 pages of new material with a superb selection of Fawcett reprints, but once the character was picked up for a children’s TV show, the comic was again slimmed down to a cheaper standard format and increased publication frequency.

Maggin and Oksner led in #13 as ‘The Case of the Charming Crook!’ revealing how a felon manages to synthesise “essence of Sunny Sparkle†to make his crimes easier. This is followed by clip-art historical features ‘The Seven Deadly Enemies of Man!’, ‘Friends of the Shazam Family!’ and ‘Mary Marvel’s Fashion Parade!’ before Oksner returns to familiar ground as an illustrator of beautiful women in Bridwell’s Mary Marvel solo strip ‘The Haunted Clubhouse!’

The entire Marvel Family was needed in the next issue when O’Neil & Schaffenberger crafted ‘The Evil Return of the Monster Society’: a splendid action thriller serving to remind us that the Original Captain Marvel Shazam was never just about charm and comedy…

You know what fans are like: they had been arguing for decades – and still do – over who is best (for which read “who would win if they fought?â€) out of Superman or Captain Marvel, so it’s amazing that a face off meeting took as long as it did to materialise.

However, despite the cover, the lead strip in #15 wasn’t it. Instead fans had to be content with a notoriously familiar guest villain when Mr. Mind and ‘Captain Marvel Meets… Lex Luthor!?!’: the work of O’Neil, Oksner and veteran inker (Phillip) Tex Blaisdell, who had worked un-credited on many DC strips over the decades, as well as drawing Little Orphan Annie, On Stage and many others.

Bridwell & Schaffenberger closed the issue with an excellent crime-caper in ‘The Man in the Paper Armor!’, preceded by clip features ‘Shazam’s Scientists and Inventors’ and ‘A Tour of American Cities with Captain Marvel!’

Schaffenberger kicked off #16 with Maggin’s ‘The Man who Stole Justice’; a taut thriller involving the incarnation of the one of the iconic Seven Deadly Enemies of Man (Sins to you and me) and a key part of the legend since the strip’s inception. Bridwell & Oksner utilised another Deadly Enemy in Mary Marvel solo story ‘The Green-Eyed Monster!’, but aliens and a Hippie musician were the antagonists in the feature-length tale leading off #17, the last 100-page issue. ‘The Pied Un-Piper’ is a tongue-in-cheek thriller from O’Neil & Schaffenberger, whereas a slightly more modern tone tinged the whimsy in #18’s ‘The Celebrated Talking Frog of Blackstone Forest!’ (Maggin & Oksner) and Bridwell & Schaffenberger’s CM Jr. clash with Sivana Jr. in ‘The Coin-Operated Caper’, albeit not enough to deaden the charm…

DC pulled out all the stops with their new baby. Production ace Jack Adler teamed with illustrators such as Nick Cardy, Murphy Anderson, Beck and Oksner to create a string of amazing photo/drawn art covers. The experiments ended with 7, but even so, it gave the title a unique presence on newsstands of the time and you can also enjoy them here.

Although controversial amongst older fans, the 1970’s incarnation of Captain Marvel has a tremendous amount going for it. Gloriously free of angst and agony, beautifully, simply illustrated, and wittily scripted, these are clever, funny, wholesome adventures that would appeal to any child and positively promote a love of graphic narrative. There’s a horrible dearth of exuberant fun superhero adventure these days so isn’t it great that there’s somewhere to go for a little light action again?

© 1973, 1974, 1975, 2019 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved.