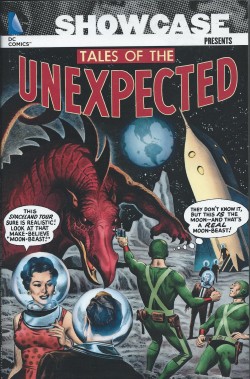

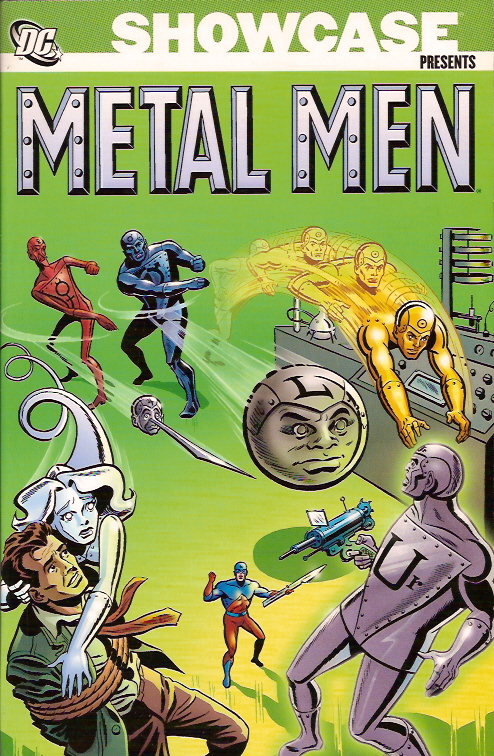

By Robert Kanigher, Bob Haney, Ross Andru, Mike Esposito, Ramona Fradon & various (DC Comics)

SBN: 978-1-4012-1559-0 (TPB)

Dc comics have a vast unexploited wealth and variety of comics classics that remain untapped for modern fans. This especially kid-friendly series is one that really should be back in digital and paperback archival tomes…

In contrast to his gritty war and adventure scripts Robert Kanigher usually kept his fantasy and superhero comicbook tales light, visually intriguing and often extremely outlandish… and that’s certainly the case with these eccentric artificial heroes who briefly caught the early 1960’s zeitgeist for bizarre and outrageous light-hearted adventure.

The Metal Men first appeared in four consecutive issues of National/DC’s try-out title Showcase: legendarily created over a weekend by Kanigher after an intended feature blew its press deadline. The prospect was rapidly rendered by the art-team of Ross Andru & Mike Esposito: a last-minute filler that attracted a large readership’s eager attention. Within months of their fourth and final adventure, the gleaming gladiatorial gadgets were stars of their own title.

This first cheap and cheerful monochrome compendium collects the electrifying contents of Showcase #37-40, Metal Men #1-15 (spanning (March/April 1962 to September 1965) as well as the first of their nine team-up appearances in Brave and the Bold: specifically issue #55.

The alchemical excitement began in Showcase #37 (March/April 1962) with ‘The Flaming Doom!’ wherein an horrific radioactive antediluvian beast flies out of a melting polar glacier (geez! Topical) to mindlessly devastate humanity’s great cities. Helpless to stop the creature, the American military desperately approaches brilliant young technologist Dr. Will Magnus for a solution. He rapidly constructs a doomsday squad of self-regulating, highly intelligent automatons, patterned after Tina, a prototype “female†robot constructed from platinum and malleable memory ceramic, governed by a tiny supercomputer dubbed a “Responsometerâ€.

This miracle of micro-engineering not only simulates – or perhaps originates – thought processes and emotional character for the robots, but constantly reprograms the base form – allowing the mechanoids to change their shapes.

Magnus patterns his handmade heroes on pure metals, with Gold as leader of a tight-knit team consisting of Iron, Lead, Mercury and Tin warriors. Thanks to their responsometers, each robot specialises in physical changes based on its elemental properties but – due to some quirk of programming – the robots also develop personality traits mimicking the metaphorical attributes of their base metal.

Tina is especially intransigent, believing herself to be passionately in love with her dashing creator…

As soon as they’ve introduced themselves, the shining squad sets off to confront the deadly monster in a flying rocket-saucer and, after a terrible battle, succeed at the cost of their own brief lives…

In Showcase #38 a very public campaign to reconstruct the Metal Men results in Magnus building them anew. However, their unique characters are gone and they promptly fail in battle against a Soviet-backed Nazi scientist’s robotic marauder… until the desperate Yankee inventor manages to recover their original responsometers in ‘The Nightmare Menace!’

‘The Deathless Doom!’ then pits the malleable machines against an animated glassine tank used to store toxic residues from failed experiments by genius chemist Professor Norton. The intermingled waste products combine to create a deadly new life form dubbed Chemo who (Which? What?) would become one of the greatest menaces in the DC universe…

The Showcase trial run concluded with September/October 1962 issue as ‘The Day the Metal Men Melted!’ sees Chemo return just as Magnus’ previous exposure to the Toxic Terror coincidentally transforms the inventor into a radioactive, metallic giant. Acutely aware of his dangerous condition, Magnus exiles himself to deep space and manages to take Chemo with him where, luckily, the outer limits provide the valiant scientist with an unexpected cure…

Whereas the first three tales were relatively straight dramas, with this yarn rationalistic physics began giving way to fantastic fringe science and comedic elements began to proliferate. By increasingly capitalising on the Metal’s Men quirky characters, successive stories became as much fantasy as drama.

Metal Men #1 launched with an April/May 1963 cover-date, detailing the astonishing ‘Rain of the Missile Men’, in which alien robot Z-1 falls in love with Tina from astronomically afar and builds innumerable hordes of duplicates of himself to claim her. When his automaton army invades Earth, only Tina survives to the end of the issue…

At this point Magnus is becoming increasingly schizophrenic about the desperately lovesick and fiercely jealous Tina: alternately berating her impossible emotions then moping and missing her after he’s donated the troublesome toy to a museum… Huh! Robot Women: can’t live with them, can’t make them whatever you want them to…

Kanigher’s greatest ability was always his knack for dreaming up outlandish visual situations and bizarre emotive twists. ‘Robots of Terror’ describes how the frustrated Tina constructs her own mechanical Doc Magnus, which turns evil and develops an equally iniquitous team of elemental warriors – Barium, Aluminium, Calcium, Zirconium, Sodium and Plutonium – to battle the recently reconstructed Metal Men, after which #3’s ‘The Moon’s Mechanical Army!’ sees the team undertake a lunar search for the Platinum Bombshell after she sacrifices herself to save them all. In the process, they inadvertently bring an uncontrollable amoebic monster back to Earth…

Tin was the meekest Metal and most lacking in confidence, but in ‘The Bracelet of Doomed Heroes!’ a Giant-Alien-Robot-Amazon-Queen takes a shine to the timid tyke and shanghaies him to her distant planet. When his alchemical comrades come to the rescue they are trapped and enslaved until Tin turns the tide in the concluding ‘Menace of the Mammoth Robots!’

Back on Earth, the Metal Men battle a Gas Gang (Oxygen, Helium, Chloroform, Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Dioxide) of evil mechanical marauders after cosmic rays made Magnus evil and electronic on ‘The Day Doc Turned Robot!’, after which ‘The Living Gun!’ finds a fully-restored team confronting a colossal monster formed from a runaway solar prominence.

Metal Men #8 has the team take a little blind boy on a jaunt to another world, only to be trapped by extraterrestrial robots in ‘The Playground of Terror!’ before young Billy saves the day in the concluding battle with ‘The Robot Juggernaut!’

‘Revolt of the Gas Gang!’ relates how Doc is forced to revive the vaporous villains when the Metal Men are accidentally merged into one monolithic menace, after which the tightly continuous sagas briefly halt here to include a team-up tale from Brave and the Bold #55 (August/September 1965) in which writer Bob Haney and illustrators Ramona Fradon & Charles Paris detail the ‘Revenge of the Robot Reject’.

When a series of suspicious lab accidents destroys the Heavy Metal Heroes, distraught Doc is menaced by rogue robot Uranium and its silver metal lover Agantha, until size-changing champion Professor Ray Palmer intervenes as the all-conquering Atom, after which the scrap-heap scrappers are once more resurrected to end the evil automaton’s nuclear threat forever.

Meanwhile, back in Metal Men #11, by usual suspects Kanigher, Andru & Esposito, ‘The Floating Furies!’ finds the resourceful robots both upon and beneath the briny seas, battling intelligent mines, giant crustaceans and even King Neptune, before Z-1’s inexhaustible horde of Missile Men returns to ‘Shake the Stars!’, after which the ‘Raid of the Skyscraper Robot’ introduces a new Metal Man… of sorts.

When lonely Tin builds himself a girlfriend from a toy kit, neither is able to withstand the mockery of fellow metal Mercury. The automatic lovers flee Earth, only to encounter a devastated mobile planet of monolithic mechanical monsters which follow them back here – only to face final defeat at the gleaming hands of the reunited team.

Chemo returns to disable – but never defeat – the Metal Men in #14’s ‘The Headless Robots!’ before this initial instalment of elemental epics concludes with ‘The Revenge of the Rebel Robots!’ in which the fashionable fad for acronymic spy stories pitches the Sterling Stalwarts into combat with a giant spy machine from the subversive secret society B.O.L.T.S.! (…and no, I don’t know what it stands for…)

Wildly imaginative, weirdly enthralling and brilliantly daft, these full-on, frantic fantasies are a superb slice of the nostalgic good old days, when every day lasted a week and the world was stuffed to bursting with dinosaurs, robots and monsters. Sometimes, if you buy the right book, you can still get all those thrills at once, so let’s hope it’s not long before these marvellous yarns are back in vogue… and print…

© 1962-1965, 2007 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved.