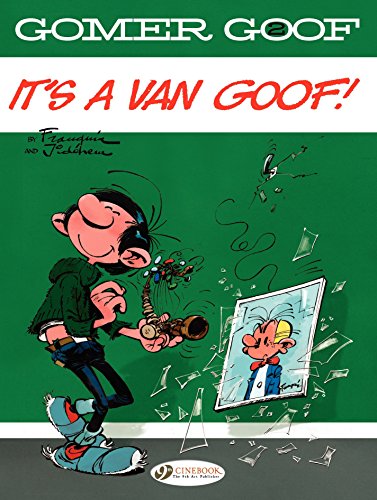

By André Franquin, Jidéhem & Delporte, translated by Jerome Saincantin (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-1-84918-365-9 (PB Album)

Like so much in Franco-Belgian comics, it all started with Le Journal de Spirou. The magazine had debuted on April 2nd 1938, with its engaging lead strip created by Rob-Vel (François Robert Velter). In 1943 publishing giant Dupuis purchased all rights to the comic and its titular star, after which comic-strip prodigy Joseph Gillain (“Jijéâ€) took the helm.

In 1946 Jijé’s assistant André Franquin assumed the creative reins, gradually side-lining the previously-established short gag vignettes in favour of extended adventure serials. He introduced a broad, engaging cast of regulars; creating phenomenally popular magic animal Marsupilami (first seen in Spirou et les héritiers in 1952 and eventually a spin-off star of screen, plush toy store, console games and albums in his own right) to the mix.

Franquin continued crafting increasingly fantastic tales and absorbing Spirou sagas until his resignation in 1969. During that period the creator was deeply involved in the production of the weekly Spirou comic

Franquin was born in Etterbeek, Belgium on January 3rd 1924. Drawing from an early age, the lad only began formal art training at École Saint-Luc in 1943. When the war forced the school’s closure a year later, he found work at Compagnie Belge d’Animation in Brussels where he met Maurice de Bévère (AKA Lucky Luke creator “Morrisâ€), Pierre Culliford (Peyo, creator of The Smurfs and Benny Breakiron) and Eddy Paape (Valhardi, Luc Orient).

In 1945 all but Peyo signed on with Dupuis, and Franquin began his career as a jobbing cartoonist/illustrator, producing covers for Le Moustique and scouting magazine Plein Jeu. During those early days, Franquin and Morris were being tutored by Jijé, who was the main illustrator at Spirou. He turned the youngsters and fellow neophyte Willy Maltaite (AKA “Will†– Tif et Tondu, Isabelle, Le jardin des désirs) into a smoothly functioning creative bullpen known as La bande des quatre or “Gang of Fourâ€. They later reshaped and revolutionised Belgian comics with their prolific and engaging “Marcinelle school†style of graphic storytelling…

Jijé handed Franquin all responsibilities for the flagship strip part-way through Spirou et la maison préfabriquée (Spirou #427, June 20th 1946). He ran with it for the next two decades; enlarging the scope and horizons of the feature until it became purely his own. Almost every week fans would meet startling new characters such as comrade/rival Fantasio or crackpot inventor and Merlin of mushroom mechanics the Count of Champignac.

Spirou &Fantasio became globe-trotting journalists, travelling to exotic places, uncovering crimes, exploring the fantastic and clashing with a coterie of exotic arch-enemies. However, throughout all that time Fantasio was still a full-fledged reporter for Le Journal de Spirou and had to pop into the office all the time.

Sadly, lurking there was an accident-prone, big-headed junior in charge of minor jobs and dogs-bodying. His name was Gaston Lagaffe…

There’s a long history of fictitiously personalising the mysterious creatives and all those arcane processes they indulge in to make our favourite comics, whether its Stan Lee’s Marvel Bullpen or DC Thomson’s lugubrious Editor and underlings at the Beano and Dandy. Let me assure you that it’s a truly international practise and the occasional asides on text pages featuring well-meaning foul-up/office gofer Gaston – who debuted in #985, February 28th 1957 – grew to be one of the most popular and perennial components of the comic.

I’d argue, however, that current iteration Gomer Goof (his name is taken from an earlier, abortive attempt to introduce the character to American audiences) is an unnecessary step. The quintessentially Franco-Belgian tone and humour doesn’t translate particularly well (la gaffe translates as “the blunderâ€) and contributes nothing here. When the big idiot surprisingly appeared in a 1970s Thunderbirds annual as part of an earlier syndication attempt, he was rechristened Cranky Franky. Perhaps they should have kept the original title…

In terms of entertainment schtick and delivery, older readers will certainly recognise beats of Jacques Tati and timeless elements of well-meaning self-delusion British readers will recognise from Some Mothers Do Have ‘Em or Mr Bean. It’s slapstick, paralysing puns, pomposity lampooned and no good deed going noticed, rewarded or unpunished…

This second album-sized paperback compilation (available also in digital formats) consists of half-page shorts, longer cartoon strips and comedic text story “reports†from the comic’s editorial page as well as ultimately full episodes of madcap buffoonery.

As previously stated, Gomer is employed (let’s not dignify or mis-categorise what he does as “workâ€) at the Spirou offices, reporting to go-getting hero journalist Fantasio and generally ignoring the minor design jobs like paste-up and reading readers’ letters (the official reason why fans requests and suggestions are never answered…) he’s paid to handle.

He’s lazy, opinionated, forgetful and eternally hungry and his most manic moments stem from cutting corners or stashing and illicitly consuming contraband food in the office…

These characteristics frequently lead to clashes with police officer Longsnoot and fireman Captain Morwater, but the office oaf remains eternally easy-going and incorrigible. Only two questions are really important here: why does Fantasio keep giving him one last chance, and what can gentle, lovelorn Miss Jeanne possible see in the interfering, self-opinionated idiot?

Originally released in 1968 as sixth volume Gaston – Des gaffes et des dégâts, the translated chaos (available in paperback and digital formats) commences with a quartet of short, sharp two-tier episodes involving Gomer’s office innovations and war of nerves with Longsnoot, before the first illustrated text “report†from the comic’s editorial page details a catastrophe in glass in ‘Whistle While You Work’.

A second, entitled ‘Letter from the Countryside’ shares space with a calamitous seaside excursion and selection of rural escapades turned camping Armageddon…

Prose missive ‘Gomer Writes Us’ (on the joys of go-karting) leads to a ‘Conversation on a Street Corner’ and details on a new kind of music in ‘Honky-honk copper’, after which computer-assisted design is proved to be one more thing Gomer must never attempt in ‘Chorus and Bridge’…

The remainder of the volume is all picture strip pandemonium as the imbecile’s attempts at rooftop cookery lead to aviation disasters, projectile peril, standoffs on staircases and a unique form of petty theft…

Rallying and racing capture his mayfly attention-span, but a hunt for a new vehicle never succeeds and Gomer always returns to his appallingly decrepit and dilapidated Fiat 509 auto(barely)mobile, but the fool is set in his ways and even doctors can’t fix or remove him…

However, somebody rational really should have foreseen what the slacker was capable of when he brought in a chemistry set…

Far better enjoyed than précised or described, these strips allowed Franquin and fellow scenarists Yvan Delporte and Jidéhem (in reality, Jean De Mesmaeker: his analogue is a regular in the strips as an explosively irate and unfortunate foil for the Goof) to flex their whimsical muscles and even subversively sneak in some satirical support for their beliefs in pacifism and environmentalism, but at their core the gags remain supreme examples of all-ages comedy: wholesome, barbed, daft and incrementally funnier with every re-reading.

What’s stopping you from Goofing off?

© Dupuis, Dargaud-Lombard s.a. 2017 by Franquin. All rights reserved. English translation © 2017 Cinebook Ltd.