By Hergé & various; translated by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper & Michael Turner (Egmont)

ISBN: 978-1-40520-621-1 (PB)

Georges Prosper Remi РAKA Herg̩ Рcreated a true masterpiece of graphic literature with his astounding yarns tales of a plucky boy reporter and his entourage of iconic associates. Singly, and later with assistants including Edgar P. Jacobs, Bob de Moor and the Herg̩ Studio, Remi completed 23 splendid volumes (originally produced in brief instalments for a variety of periodicals) that have grown beyond their popular culture roots and attained the status of High Art.

It’s only fair, though, to ascribe a substantial proportion of credit to the many translators whose diligent contributions have enabled the series to be understood and beloved in 38 languages. The subtle, canny, witty and slyly funny English versions are the work of Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper & Michael Turner.

On leaving school in 1925, Remi worked for Catholic newspaper Le Vingti̩me Si̩cle where he fell under the influence of its Svengali-like editor Abbot Norbert Wallez. The following year, the young artist Рa passionate and dedicated boy scout Рproduced his first series: The Adventures of Totor for monthly Boy Scouts of Belgium magazine.

By 1928 Remi was in charge of producing the contents of the parent paper’s children’s weekly supplement Le Petit Vingtiéme and unhappily illustrating The Adventures of Flup, Nénesse, Poussette and Cochonette when Abbot Wallez urged the artist to create an adventure series. Perhaps a young reporter who would travel the world, doing good whilst displaying solid Catholic values and virtues?

And also, perhaps, highlight and expose some the Faith’s greatest enemies and threats…?

Having recently discovered the word balloon in imported newspaper strips, Remi decided to incorporate this simple yet effective innovation into his own work. He would produce a strip both modernistic and action-packed.

Beginning January 10th 1929, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets appeared in weekly instalments, running until May 8th 1930.

Accompanied by his garrulous dog Milou (Snowy to us Brits), the clean-cut, no-nonsense boy-hero – a combination of Ideal Good Scout and Remi’s own brother Paul (a soldier in the Belgian Army) – would report back all the inequities of the world, since the strip’s prime conceit was that Tintin was an actual foreign correspondent for Le Petit Vingtiéme…

The odyssey was a huge success, assuring further – albeit less politically-charged and controversial – exploits to follow. At least that was the plan…

During the Nazi Occupation of Belgium, Le Petit Vingtiéme was closed down and Hergé was compelled to move the popular strip to the occupiers’ preferred daily newspaper Le Soir. He diligently continued producing strips for the duration, but in the period following Belgium’s liberation was accused of being a collaborator and even a Nazi sympathiser.

It took the intervention of Resistance hero Raymond Leblanc to dispel the cloud over Herg̩, which he did by simply vouching for the cartoonist and by providing the cash to create a new magazine РLe Journal de Tintin Рwhich Leblanc published and managed. The anthology comic swiftly achieved a weekly circulation in the hundreds of thousands.

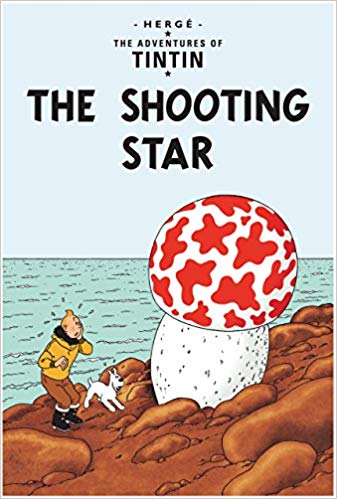

With this tale we enter the Golden Age of an iconic creator’s work. Despite being produced whilst Belgium was under the control of Nazi Occupation Forces during World War II, the qualitative leap in all aspects of Hergé’s creativity is potent and remarkable.

After his homeland fell to the invaders in 1940, Georges Remi’s brief military career was over. He was a reserve Lieutenant, working on The Land of Black Gold when called up, but the swift fall of Belgium meant that he was back at his drawing board before year’s end, albeit working for a new paper on a brand-new adventure. He would not return to the unfinished Black Gold, with its highly anti-fascistic subtext, until 1949.

L’Étoile mystérieuse ran in Le Soir (the little nation’s premiere French-language newspaper and a crucial tool for the Germans to control minds, if not hearts) from October 20th 1941 to May 21st 1942: the second of six extraordinary tales of light-hearted, escapist thrills, blending strong plots and deep characterisation to create a haven of delight from the daily horrors of everyday life then and remain a legacy of joyous adventure to this day.

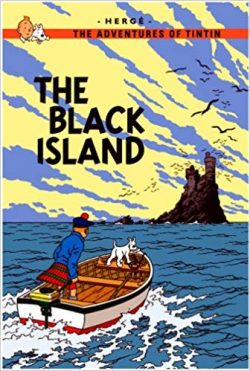

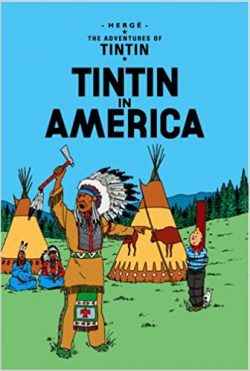

On completion it was collected as a full-colour book in 1942 and later serialised in French newspaper Coeurs Vaillants (from June 6th 1943). It was among a flurry of reissues of earlier albums – all but Tintin in America and The Black Island, both set in countries Germany was still at war with…

In 1954 it was remastered by Studio Hergé, to remove certain anti-Semitic and anti-American passages and imagery he had been forced to include by the paper’s controllers, and comes to us as a stunning piece of apocalyptic, sci-fi flavoured adventure…

The remastered edition of The Shooting Star was one of the first tales re-issued after World War II, due no doubt to its relatively escapist plot… it’s practically an old-fashioned pulp thriller.

It begins with the world gripped in terror as a fiery meteor is detected hurtling towards Earth. The end times are narrowly averted only by the sheerest chance, as the heavenly body narrowly misses our frail planet, although when a relatively small chunk breaks off, scientists find that it contains an unknown metal of immense potential value. And so begins a fantastic race to find and claim the fallen meteorite…

A party of European scientists charters the survey ship “Auroraâ€, with boozy stalwart Captain Haddock commanding and Tintin aboard as official Press representative. Frantically sailing north to the Pole, they discover that they are in competition with the unscrupulous forces of the evil capitalists of the Bohlwinkel Bank, whose rival expedition uses every dirty trick imaginable to sabotage or delay the scientists.

After a truly Herculean effort and by sheer dint of willpower – not to say spectacular bravery – Tintin is the first to claim their floating prize and successfully defends it from the villainous Bohlwinkel crew, but the fallen star itself is a far greater menace, as its mysterious and exotic composition induces monstrous gigantism in earthly organisms. Tintin and Snowy must survive assaults by mutated insects and plants before the breathtaking conclusion of this splendid tale.

Manifestly as the world experienced a new Dark Age, Hergé was concentrating on the next -Golden – one…

These ripping yarns for all ages are an unparalleled highpoint in the history of graphic narrative. Their unflagging popularity proves them to be a worthy addition to the list of world classics of literature, and stories you and your entire clan should know.

The Shooting Star: artwork © 1946, 1974 Editions Casterman, Paris & Tournai. Text © 1961 Egmont UK Limited. All rights reserved.