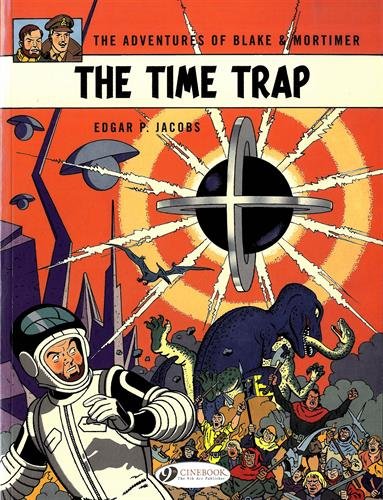

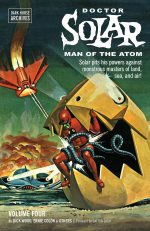

By Dick Wood, Roger McKenzie, Don Glut, Al McWilliams, Ernie Colón, José Delbo, Dan Spiegle, Jesse Santos, George Wilson & various (Dark Horse Books)

ISBN: 978-1-59307-825-6 (HB) 978-1-61655-512-2 (TPB)

Comics colossus Dell/Gold Key/Whitman had one of the most complicated publishing set-ups in history, but that didn’t matter one iota to kids of all ages who consumed their vastly varied product. Based in Racine, Wisconsin, Whitman had been a crucial component of the monolithic Western Publishing and Lithography Company since 1915: drawing upon commercial resources and industry connections that came with editorial offices on both coasts. They even boasted a subsidiary printing plant in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Another connection was with fellow Western subsidiary K.K. Publications (named for licensing legend Kay Kamen who facilitated extremely lucrative “license to print money†merchandising deals for Walt Disney Studios between 1933 and 1949).

From 1938, the affiliated companies’ comic book output was released under a partnership deal with a “pulps†periodical publisher under the umbrella imprint Dell Comics – and again those creative staff and commercial contacts fed into the line-up of the Big Little, Little Golden and Golden Press books for children. This partnership ended in 1962 and Western had to swiftly reinvent its comics division as Gold Key.

Western Publishing had been a major player since comics’ earliest days, blending a huge tranche of licensed titles including newspaper strips, TV tie-in and Disney titles (like Nancy and Sluggo, Tarzan, or The Lone Ranger) with in-house originations such as Turok, Son of Stone, Brain Boy, and Kona Monarch of Monster Isle.

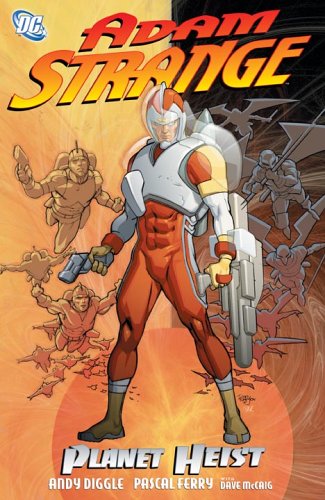

Dell and Western split just as a comic book resurgence triggered a host of new titles and companies, and a superhero boom. Independent of Dell, new outfit Gold Key launched original adventure titles including Mighty Samson; Magnus – Robot Fighter; M.A.R.S. Patrol, Total War; Space Family Robinson and – in deference to the atomic obsession of the era – a cool, potently understated thermonuclear white knight…

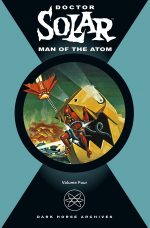

The new company’s most recognisable and significant stab at a superhero bore the rather unwieldy codename of Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom, who debuted in an eponymous title cover-dated October 1962 and thus on sale in the last days of June – Happy 60th Birthday Doc! – sporting a captivating painted cover by Richard M. Powers which made it feel like a grown up book rather than a simple comic.

With #3, George Wilson took over the iconic painted covers: a glorious feature that made the hero unique amongst his costumed contemporaries…

This fourth and final collection spans April 1968 via a 12-year hiatus – all the way to March 1982, encompassing a period when superheroes again faded from favour, whilst supernatural themes proliferated in comics books. Gold Key had their own stable of magical mystery titles: anthologies such as Boris Karloff Tales of Mystery, Ripley’s Believe it or Not, Grimm’s Ghost Stories and The Twilight Zone. They even ran a few character-driven titles including Dagar the Invincible, Tragg and the Sky Gods and The Occult Files of Dr. Spektor.

Included in this volume are the contents of Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom #23-31, plus a guest cameo from The Occult Files of Dr. Spektor #14: a very mixed bag preceded by an Introduction from the late Batton Lash (Supernatural Law; Archie Meets the Punisher; Wolff and Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre).

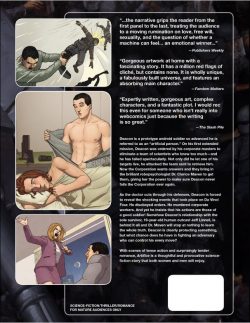

The Supreme Science Hero was born when a campaign of sabotage at US research base Atom Valley culminated in the death of Dr. Bentley and accidental transmutation of his lab partner Doctor Solar into a (no longer quite) human atomic pile with incredible, impossible and apparently unlimited powers and abilities. Of course, his mere presence is lethal to all around him until scientific ingenuity devises – with dutiful confidantes girlfriend Gail Sanders and mentor Dr. Clarkson – a few brilliant work-arounds…

Solar was created by Paul S, Newman but the majority of later tales were written by Golden Age all-star Dick Wood (Sky Masters of the Space Force; Crime Does Not Pay; The Phantom; Mandrake the Magician; Flash Gordon and countless others). In this final volume a number of artists shared duties, beginning with Alden “Al†McWilliams (Danny Raven/Dateline: Danger; Star Trek, Flash Gordon; Twilight Zone; Buck Rogers; Justice Inc.; Star Wars and so much more) who drew the first tale here.

The atomic adventuring resumed with the latest ploy of evil mastermind Nuro: Solar’s nemesis and a madman who defeated death by implanting his personality inside a super-android. ‘King Cybernoid Strikes Part I & II’ (#23: cover-dated April 1968 by Wood & McWilliams) sees the malevolent man-machine escape his destroyed citadel of evil to replace a billionaire philanthropist, infiltrate Atom Valley and orchestrate his enemy’s demise by shutting down the nuclear reactors Solar needs to sustain his existence. The hero’s plan to survive seems like nuclear suicide but happily works out…

Ernie Colón was next to render the Atomic Ace beginning with #24’s (July 1968) Wood-written ‘The Deadly Trio Part I & II’.

Born in Puerto Rico on July 13th 1931, Ernie Colón Sierra was a multi-talented maestro of the American comics industry whose work delighted generations of readers. Whether as artist, writer, colourist or editor, his contributions affected the youngest of comics consumers (Monster in My Pocket, Richie Rich, Casper the Friendly Ghost at Harvey Comics and Marvel’s Star Comics imprint) to the most sophisticated connoisseur with strips.

His mature-reader material comprised newspaper sci fi classic Star Hawks, comic book graphic novels Ax, Manimal, The Medusa Chain and more, and comics as wide-ranging as Vampirella, Battlestar Galactica, Arak, Son of Thunder, Damage Control, Doom 2099, I… Vampire, Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld, and Airboy. He also drew the 1990s revival of Magnus: Robot Fighter for Valiant amongst so very many others.

Colón was master of many trades and served as an innovative editor, journalist, historian and commentator as well. Amongst his vast output were sophisticated experimental works and seminal genre graphic novels done in collaboration with Harvey Comics/Star Comics collaborator Sid Jacobson. These include The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation, After 9/11: America’s War on Terror, Che: a Graphic Biography and Vlad the Impaler. In 2010 they released Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography and 2014’s The Warren Commission Report: A Graphic Investigation into the Kennedy Assassination with Gary Mishkin.

While diligently hard at work on newspaper strip SpyCat (Weekly World News 2005-2019) he sought other challenges, like historical works A Spy for General Washington and The Great American Documents: Volume 1, both collaborations with his author wife Ruth Ashby. He died on August 8th 2019…

Here he adds an edge of high-octane dramatic tension to Solar’s exploits as the fugitive King Cybernoid unleashes three deadly war machines, each the ultimate weapon in its preferred environment of earth, air and water and each a crucial component in a lethal booby trap…

‘The Lost Dimension Part I & II’ (#25, October) began a continued tale with Atom Valley’s teleportation experiments opening Earth to attacks from an evil parallel dimension. Impatient to solve the mystery of vanishing test subjects, Gail’s nephew and resident teen super-genius Hamilton Mansfield Lamont uses the apparatus on himself and is captured by mirror universe duplicates. When Solar follows he uncovers a plot to invade and conquer our universe and must use his intellect as well as atomic powers to resist the wicked facsimiles’ plans ‘When Dimensions Collide parts I & II’ (#26 January 1969).

A new year saw a fresh illustrative hand. Argentinian illustrator José Delbo (Billy the Kid; Mighty Samson; Yellow Submarine; The Monkees; Wonder Woman; Superman; Batman; Turok, Son of Stone; Transformers,) had been a prolific US comics illustrator since 1965, and was a valued contributor to Gold Key’s licensed titles. He took on the Atomic Ace in a 2-issue run that spanned 12 years, beginning with Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom #27.

Cover-dated April 1969, the done-in-one yarn written by Wood saw the titanic troubleshooter clashing again with cyborg Nuro. It began at a British radio telescope as the hero sought to prevent marauding energy beings using the installation to invade Earth via ‘The Ladder to Mars’. After solving ‘The Mystery Message’, Solar triumphs in an outer space ‘Battle of the Electronic Fighters’.

This was the last appearance for quite a while, as the taste for men in tights waned. A guest shot from the genre-experimental 1970s was a rare treat, before a superhero resurgence saw Solar’s return in what I’m assuming was an inventory tale that had sat in a drawer since cancellation. In the meantime, Gold Key had undergone a few changes and was now using the publishing umbrella of “Whitmanâ€.

Cover-dated April 1981, Doctor Solar, Man of the Atom #28 featured Wood & Delbo’s ‘The Dome of Mystery’: a traditional 2-chapter saga that saw Nuro use a deadly force field dome to destroy his enemies. Although initially helpless against ‘The Movable Fortress’, Solar’s persistence and ingenuity eventually triumphs in ‘The Dome of Mystery: An Army of Molecules’. Also included was an informational strip by Al McWilliams ‘A Day at the Man of the Atom’s Secret Training Grounds’.

The next issue was cover-dated October 1981, with writer Roger McKenzie (Captain America; Daredevil; Next Man; Battlestar Galactica; Men of War: Gravedigger) joined by veteran artist Dan Spiegle. Criminally unsung, his career was two-pronged and incredibly long. Born in 1920, Spiegle wanted to be a traditional illustrator but instead fell – after military service in the Navy – into comics at the end of the 1940s. He was equally adept at dramatic narrative art and humorous cartooning, and his impossibly large and varied portfolio includes impeccable work on Hopalong Cassidy; Rawhide; Sea Hunt; Space Family Robinson; Blackhawk and Nemesis for DC; Crossfire; Scooby Doo; Who Framed Roger Rabbit?; Indiana Jones; the entire Hanna-Barbera stable and so much more.

In high energy action mode here, he limns the Atomic Ace’s close encounter with extradimensional energy vampire ‘Li’Rae’ and her subsequent attempt to colonise and consume Earth. The hero’s penultimate exploit was cover-dated February 1982, with McKenzie & Spiegle resurrecting the Man of the Atom’s greatest foe. When international Man of Mystery Mr. Dante gathers the world’s greatest scientist on his artificial paradise of New Atlantis, Solar soon uncovers his real identity and deadly scheme, but not before the villain unleashes a geothermal ‘Inferno’…

One month later the heroic exploits concluded with #31 and an assault by an misguided admirer of Gail’s. When actor Ron Barris gains incalculable power in a special effects accident, he targets “rival†Solar in his TV superhero role ‘When Strikes the Sentinel!’ in his deranged scheme to make her his own, but his new powers are no match for the Atomic Avenger…

The mid-70s cameo appearance previously mentioned closes this archive. It comes from The Occult Files of Dr. Spektor #14 (June 1975): a series starring a troubled mystic and supernatural troubleshooter in the classic vein. ‘The Night Lakota Died’ is by Don Glut & Jesse Santos (who also painted the cover) and finds famed ghostbuster Dr. Adam Spektor accused of murdering his assistant and lover. On the run, the magician uncovers a plot by archenemy Kareena to entrap the mage and seduce him to the side of her Dark Gods.

Her plan revolves around keeping a certain atomic superhero under her mesmeric spell, but once again the witch underestimates the resolve of the forces of light…

Enticingly restrained and understated, these Atom Age action comics offered a compelling counterpoint to the hyperbole of DC and Marvel and remain some of the most readable thrillers of the era. These tales are lost gems from a time when fun was paramount and entertainment a mandatory requirement. This is comics the way they were and really should be again…

DOCTOR SOLAR®, MAN OF THE ATOM ARCHIVES Volume 4 ® and © 1968, 1969, 1975, 1981, 1982, 2015 Random House, Inc. Under license to Classic Media, LLC. All rights reserved.