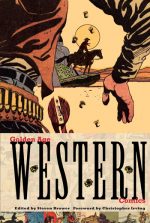

By various, compiled and edited by Steven Brower (PowerHouse Books)

ISBN: 978-1-57687-594-0

There was a time, not that very long ago, when all of popular fiction was engorged and saturated with tales of “Cowboys and Indiansâ€.

As always happens with such periodic phenomena – like the Swinging Sixties Super-Spy boom, the more recent Lonely Human/Vampire/Werewolf Boyfriend triangle or the trend for Sassy Articulate Gerbils Training Little Girls to be Sporting Stars and Master Martial Artists (I might have got that one confused) – there’s a tremendous amount of dross amidst a few spectacular gems beyond price.

On such occasions, there’s also generally a small amount of wonderful but not-quite-life-changing material that gets lost in the shuffle: carried along with the overwhelming surge of material pumped out by TV, film, comics and book producers as well as toy, game and record industries.

After World War II the American family entertainment market – which mostly meant comics, radio and the burgeoning but small television industry – became comprehensively enamoured of the clear-cut, simplistic sensibilities and easy, escapist solutions offered by Tales of the Old West; already a firmly established favourite of paperback fiction, movie serials and feature films.

I’ve often pondered on how almost simultaneously a dark, bleak, nihilistic and oddly left-leaning Film Noir genre quietly blossomed alongside that wholesome revolution, seemingly for the cynical minority of entertainment snobs and intellectuals who somehow knew that the returned veterans still hadn’t found a Land Fit for Heroes… but that’s a thought for another time and a different review.

Even though comicbooks had included western heroes from the very start – there were cowboy strips in the premier issues of both Action Comics and Marvel Comics – the post-war years saw a vast outpouring of anthology titles with new gun-toting heroes to replace the rapidly-dwindling supply of costumed Mystery Men, and – true to formula – most of these pioneers ranged from transiently mediocre to outright appalling. To be fair, though, over the next decade a few genuine masterpieces did float to the surface of that crowded pool: Toth’s Johnny Thunder and Doug Wildey’s Outlaw Kid being the first to come to mind…

With every comicbook publisher turning hopeful eyes westward, it was natural that most of the actual historical figures would quickly find a home and – of course – facts counted little, as indeed they never had with other avenues of cowboy literature…

Europe and Britain also embraced the Sagebrush zeitgeist, producing some pretty impressive work, with France and Italy eventually making the genre their own by the end of the 1960s. Still and all, there was the rare gleam of gold and also a fair share of highly acceptable silver in American tales, and as always, the crucial difference was due to the artists and writers involved…

With all the top-line characters and properties such as Tomahawk, Rawhide Kid, or the Lone Ranger still fully owned by big concerns, this delightful and impressive hardback compilation instead gathers a broad selection of the second-string material (call ’em Sunday matinee or B-movie comics if you want) and, although there’s no Kinstler or Kubert or Kirby classics, what editor Steven Brower has re-presented here in lavish, scanned full-colour is a magnificent meat-and-potatoes snapshot of what kids of the time would have been avidly absorbing.

Sadly, historical records are awfully spotty for this period and genre but I’m cocky enough to offer a few guesses whenever the creator credits aren’t available and I’m relatively sure of my footing…

After an informative introduction from Christopher Irving and introductory essay by Brower, the rip-roaringly wholesome fun and thrills begin with Texas Tim, Ranger (from an undesignated 1948 issue of Blazing West), part of writer/Editor Richard Hughes’ superb American Comics Group line, and a veritable one-man band of creative trend following.

Hughes is an unsung hero of the industry, competing with the Big Boys in spy, humour, western, horror and superhero titles well into the 1960s – and writing the bulk of the stories himself.

In a sadly uncredited yarn (perhaps drawn by Edmond Good), the Texan lawman tracks down rustlers and foils a plot to frame an innocent man in a rollicking 8-page romp, after which movie idol Lash LaRue solves the case of ‘The King’s Ransom’ in an adventure stuffed with chases, kidnapping, fights, framed Indians and prodigal sons, originally from #56 of his own licensed title (July 1955 and perhaps drawn by John Belfi or Tony Sgroi).

Fawcett had a huge stable (Yup, I said it and I ain’t sorry, neither) of Western screen stars, and when they quit comics in 1953 the lesser properties gems not bought by DC – such as Hopalong Cassidy – were snapped up by Capitol/Charlton Comics who purchased the bulk of declining comics publishers inventory during the 1950’s…

Charlton was always a minor player in the comics leagues, paying less, selling less, and generally caring less about cultivating a fan base than the major players. But they managed to discover and train more big names in the 1960s than either Marvel or DC, and created a vast and solid canon of memorable characters, concepts and genre material.

Almost all their stuff was written by Joe Gill or Pat Masulli, although in the 1960s young tyros like Roy Thomas, Nick Cuti, Steve Skeates, Dave Kaler and Denny O’Neil all got a healthy first bite of the cherry there, and I’m fairly certain “King of Comics†Paul S. Newman was the regular Larue scripter…

‘Magic Arrow Rides the Pony Express’ hails from Youthful Publications’ Indian Fighter (1950) illustrated by S. B. Rosen and detailing how the young Seneca chief and all-around “Good Injun†saves the famed postal service from unscrupulous badmen armed only with his quiver of enchanted shafts.

Fawcett also published a certified screen-star in Tom Mix Western and here, from #15 (1949) comes ‘Tom Mix and the Desert Maelstrom’ probably drawn by Carl Pfeufer & John Jordan – as most of the strips were – wherein the legendary lawman braves a stupendous sandstorm to capture bank-robbers and save a wounded rodeo rider from destitution.

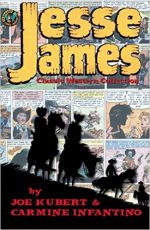

Lots of publishers plumped for public domain Jesse James to bolster their output and the one sampled here comes from Charlton’s Cowboy Western Comics #39, (June 1955, probably written by Gill & illustrated by William M. Allison). The always misunderstood gunslinger is framed for a stage hold-up and…

Magazine Enterprises produced some the very best quality comics of the 1950s and from Dan’l Boone #4, December 1955 comes the stirring saga of pioneer America ‘Peril Shadows the Forest Trail’, wherein the mythical scout and woodsman ferrets out a murderous white turncoat in a timeless thriller illustrated by the hugely undervalued Joe Certa.

‘Buffalo Belle’ also comes from the 1948 Blazing West and again displays Hughes’ mastery of short story strips as the miniskirt-wearing agent of justice deals with a dragged-up (no really!: men in skirts!) bandit in a terrific yarn possibly limned by Max Elkan or even Charles Sultan…

Also from that ACG title are the truly lovely ‘Little Lobo the Bantam Buckeroo’ – illustrated by Leonard Starr in his transitional Milton Caniff drawing style – depicting the tempestuous boy’s battle against fur thieves, plus the charming ‘Tenderfoot’ (by a frustratingly familiar artist I can’t confidently identify, but who might just be Paul Cooper) with the sissy-looking Eastern Dude dispensing western vengeance to bullies and bandits alike…

‘Little Eagle: Soldier in the Making’ also comes from Indian Fighter – illustrated with near-abstract verve by Manny Stallman – stampeding firmly into fantasy as a youthful brave equipped with magic wings tackles renegade brave Black Dog before the madman sets the entire frontier ablaze with war…

Avon Books started in 1941, created when the American News Corporation bought out pulp magazine publishers J.S. Ogilvie, and their output was famously described by Time Magazine as “westerns, whodunits and the kind of boy-meets-girl story that can be illustrated by a ripe cheesecake jacket.†By 1945 the company had launched a comicbook division as fiercely populist as the umbrella company.

They released over 100 short-lived genre titles such as Atomic Spy Cases, Bachelor’s Diary, Behind Prison Bars, Campus Romance, Gangsters and Gun Molls, Slave Girl Comics, War Dogs of the U.S. Army, White Princess of the Jungle and many others, all aimed – even the funny animal titles like Space Mouse and Spotty the Pup! – at a slightly older and more “discerning†audience and all illustrated by some of the best artists working at the time.

Many if not most sported lush painted covers that were both eye-catching and beautiful.

Six of their titles had respectable runs: Peter Rabbit, Eerie, Wild Bill Hickock, outrageous “Commie-busting†war comic Captain Steve Savage, Fighting Indians of the Wild West and their own magnificently illustrated fictionalised adventures of Jesse James.

‘Terror at Taos’ originated in Avon’s Kit Carson #6 (March 1955, but is reprinted here from Fighting Indians of the Wild West), pitting the famed scout against corrupt officials and traitorous wagon masters in the Commancheria territory; all lavishly rendered by the superb Jerry McCann.

Next up is ‘Young Falcon and the Swindlers’ from Fawcett’s Gabby Hayes Western #17 (April 1950) by an artist doing a very creditable impression of Norman Maurer, wherein the lost prince of the Truefeather Tribe tracks down crooked assayers who bilked him of his rightful pay, after which ‘Annie Oakley’ (Cowboy Western Stories # 38, April/May 1952) finds the famed sharpshooter hunting bandits in a canny 4-page quickie illustrated by Jerry Iger under the pen-name Jerry Maxwell.

Charlton’s back catalogue also provided ‘Flying Eagle in Golden Treachery’ from Death Valley #9 October 1955, wherein the noble brave foils white claim-jumpers togged up like Indians.

‘Cry for Revenge’ (Cowboy Western #49 May/June 1954) then sees venerable Fawcett star Golden Arrow hunt down more murderous whites posing as Red Men to drive settlers off their land in a gripping (Gill?) yarn illustrated by Dick Giordano & Vince Alascia.

‘Chief Black Hawk and his Dogs of War’ was a historical puff-piece also from Kit Carson #6 with artist Harry Larsen delineating the rise and fall of the legendary Sauk war chief after which Giordano & Alascia’s ‘Triple Test’ (Cowboy Western #49 May/June 1954) laconically describes the dangers of marrying in a rare, wry light-hearted tale from an age of mostly shoot-and-swipe sagas…

Gabby Hayes Western #17 also provided an adventure of the World’s Most Successful Sidekick himself (No, seriously: Hayes was the comedy stooge to almost every cowboy in Tinsel Town, from Roy Rogers and Hopalong Cassidy to Randolph Scott and John Wayne).

‘The Big Game Hunt’ is a fun-filled riot as the garrulous old coot takes the wind out of a snobby globe-trotting safari addict and saves the life of a cantankerous moose in a charming rib-tickler probably written by Rod Reed or Irwin Schoffman and illustrated by Leonard Frank.

The last tales in this tome are all from Charlton; starting with the Giordano & Alascia ‘Breakout in Rondo Prison’ (Range Busters #10 September 1955) wherein hard-riding trio Scott, Chip and Doodle are framed for robbery in a pokey cow-town and forced to fight their way to freedom after which the action ends and sun sets with a superb costumed cowboy thriller ‘For Talon’s Nest’ from Masked Raider #2 (August 1955). Here the enigmatic mystery gunslinger is forced to defend his pet eagle’s honour in a classy classic drawn by Mike Sekowsky (and possibly inked by Standard Comics comrade Mike Peppe?)

Sadly, there’s no inclusion of Charlton’s superb and long-running Billy the Kid, Gunmaster or Cheyenne Kid features, but hopefully there’s the possibility of a follow-up volume dedicated to them…?

Within the pages of this sassy full-colour hardback (still no digital edition yet, pardners!), cow-punching aficionados – and no, it’s neither a sexual proclivity nor an Olympic sport – and all fans of charming, nostalgia-stuffed comics can (re)discover a splendid selection of range-riding rollercoaster rides about misunderstood fast-guns or noble savages compelled to take up arms against an assorted passel of low-down no-goods and scurvy owlhoots, and all the other myriad tropes and touchstones of Western mythology.

Black hats, white hats, great pictures and traditional fast gun and flying fists values – what more could you possibly ask for?

Text, compilation and editing © 2012 Steven Brower. Foreword © 2012 Christopher Irving. All rights reserved