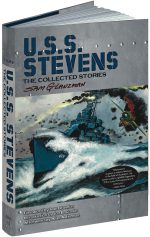

By Sam Glanzman (Dover Comics & Graphic Novels)

ISBN: 978-0-486-80158-2 (HB)

To the shame and detriment of the entire comics industry, for most of his career Sam Glanzman was one of the least-regarded creators in American comicbooks. Despite having one of the longest careers, most unique illustration styles and the respect of his creative peers, he just never got the public acclaim his work deserved. Thankfully that all changed in recent years and he lived long enough to enjoy the belated spotlight and bask in some well-deserved adulation.

Glanzman drew and wrote comics since the Golden Age, most commonly in classic genres ranging from war to mystery to fantasy, where his work was – as always – raw, powerful, subtly engaging and irresistibly compelling.

On titles such as Kona, Monarch of Monster Island, Voyage to the Deep, Combat, Jungle Tales of Tarzan, Hercules,The Haunted Tank, The Green Berets, The Private War of Willie Schultz, and especially his 1980s graphic novels A Sailor’s Story and Wind, Dreams and Dragons – which you should buy in a single volume from Dover – Glanzman produced magnificent action-adventure tales which fired the imagination and stirred the blood. His stuff always sold and at least won him a legion of fans amongst fellow artists, if not from the small, insular and over-vocal fan-press.

In later years, Glanzman worked with Tim Truman’s 4Winds outfit on high-profile projects like The Lone Ranger, Jonah Hex and barbarian fantasy Attu. Moreover, as the sublime work gathered here attests, he was also one of the earliest pioneers of graphic autobiography; translating personal WWII experiences as a sailor in the Pacific into one of the very best things to come out of DC’s 1970s war comics line…

U.S.S. Stevens, DD479 was a peripatetic filler-feature which bobbed about between Our Army at War, Our Fighting Forces, G.I. Combat, Star Spangled War Stories and other anthological battle books; quietly backing-up the cover-hogging, star-attraction glory-boys. It provided wry, witty, shocking, informative and immensely human vignettes of shipboard life, starring the fictionalised crew of the destroyer Glanzman had served on. It was, in most ways, a love story and tribute to the vessel which had been their only home and refuge under fire.

In 4- or 5-page episodes, the auteur recaptured and shared a kind of comradeship we peace-timers can only imagine and, despite the pulse-pounding drama of the lead features, us fans all knew these little snippets were what really happened when the Boys went “over thereâ€â€¦

A maritime epic to rank with Melville or Forester – and with stunning pictures too – every episode of this astounding unsung masterpiece is housed in one stunning hardback compilation (also available digitally for limp-wristed old coots like me) and if you love the medium of comics, or history, or just a damn fine tale well-told, you must have it…

That’s really all you need to know, but if you’re one of the regular crowd needful of more of my bombastic blather, a much fuller description follows…

As I’ve already stated, Glanzman belatedly enjoyed some earned attention, and this tome opens by sharing Presidential Letters from Barack Obama and George Herbert Walker Bush for his service and achievements. Then follows a Foreword from Ivan Brandon and a copious and informative Introduction by Jon B. Cooke detailing ‘A Sailor’s History: The Life and Art of Sam J. Glanzman’.

Next comes a brace of prototypical treats; the initial comic book appearance of U.S.S. Stevens from Dell Comics’ Combat #16 (April-June 1965) and the valiant vessel’s first cover spot from Combat #24, April 1967.

The first official U.S.S. Stevens, DD479 appeared after Glanzman approached Joe Kubert, who had recently become Group Editor for DC’s war titles. He commissioned ‘Frightened Boys… or Fighting Men’ (appearing in Our Army at War #218, April 1970), depicting a moment in 1942 as boredom and tension are replaced by frantic action when a suicide plane targets the ship…

A semi-regular cast was introduced slowly throughout 1970; fictionalised incarnations of old shipmates including skipper Commander T. A. Rakov, who ominously pondered his Task Force’s dispersal, moments before a pot-luck attack known as ‘The Browning Shot’ (Our Fighting Forces #125, May/June) proved his fears justified…

Glanzman’s pocket-sized tales always delivered a mountain of information, mood and impact and ‘The Idiot!’ (OAaW#220, June) is one of his most effective, detailing in 4 mesmerising pages not only the variety of suicidal flying bombs the Allies faced, but also how appalled American sailors reacted to them.

Sudden death was everywhere. ‘1-2-3’ (OFF #126, July/August) details how quick action and intuitive thinking saves the ship from a hidden gun emplacement whilst ‘Black Smoke’ (Our Army at War #222, from the same month) shows how a know-it-all engineer causes the sinking of the Stevens’ sister-ship by not believing an old salt’s frequent, frantic warnings…

All aboard ship were regularly shaken by the variety of Japanese aircraft and skill of the pilots. ‘Dragonfly’ (OFF #127, September/October) shows exactly why, whilst an insightful glimpse of the enemy’s psychological other-ness is graphically, tragically depicted in the tale of ‘The KunkÅ Warrior’ (OAaW #223, September).

A weird encounter with a wooden WWI vessel forces a ‘Double Rescue!’ (Star Spangled War Stories #153, October/November) before OFF #128’s (November/December) ‘How Many Fathoms?’ again counts the human cost of bravery with devastating, understated impact. ‘Buckethead’ (OAaW #225, November) then relates one swabbie’s unique reaction to constant bombardment.

‘Missing: 320 Men!’ (G.I. Combat #145, December 1970-January 1971) debuted Glanzman-avatar Jerry Boyle who whiled away helpless moments during a shattering battle by sketching cartoons of his astonished shipmates. ‘Death of a Ship!’ (OAaW #227, January 1971) then deals with classic war fodder as submarine and ship hunt each other in a deadly duel…

A military maritime mystery was solved by Commander Rakov in ‘Cause and Cure!’ (Our Army at War #230, March) whilst the next issue posed a different conundrum as the ship loses all power and sticks ‘In the Frying Pan!’ (April 1971).

The vignettes were always less about warfare than its effect – immediate or cumulative – on ordinary guys. ‘Buck Taylor, You Can’t Fool Me!’ (OAaW #232) catalogues his increasingly aberrant behaviour but posits some less likely reasons, after which old school hero Bos’n Egloff saves the day during the worst typhoon of the war in ‘Cabbages and Kings’(OFF #131, July/August) whilst ‘Kamikaze’ (OAa #235 August) boldly and provocatively tells a poignant life-story from the point of view of the pilot inside a flying bomb…

An informative peek at the crew of a torpedo launch station in ‘Hip Shot’ (G.I. Combat #150 October/November) segues seamlessly into the dangers of shore leave ‘In Tsingtao’ (OFF #134, November/December) whilst ‘XDD479’ (Our Army at War #238 November) reveals a lost landmark of military history.

The real DD479 was one of three destroyers test-trialling ship-mounted spotter planes. This little gem explains why that experiment was dropped…

Buck pops back in ‘Red Ribbon’ (G.I.C #151 December 1971-January 1972), sharing a personal coping mechanism for making shipboard chores less “exhilaratingâ€, whilst ‘Vela Lavella’ (OAaW #240, January 1972) captures the claustrophobic horror of night time naval engagement before ‘Dreams’ (G.I.C #152 February/March) peeps inside various heads to see what the ship’s company would rather be doing. ‘Batmen’ (OAaW #241, February) uses a lecture on radar to recount one of the most astounding exploits of the war…

Every U.S.S. Stevens episode was packed with fascinating fact and detail, culled from the artist’s letters home and service-time sketchbooks, but those invaluable memento belligeri also served double duty as the basis for a secondary feature.

The debut ‘Sam Glanzman’s War Diary’ appeared in Our Army at War #242 (March 1972): a compendium of pictorial snapshots sharing quieter moments, such as the first passage through the Panama Canal, sleeping arrangements or K.P. duties peeling spuds, and precedes an hilarious record of the freshmen sailors’ endurance of an ancient naval hazing tradition inflicted upon every “pollywog†crossing the equator for the first time in ‘Imperivm Neptivm Regis’ (OFF #136 (March/April 1972).

A second ‘Sam Glanzman’s War Diary’ (OAaW #244, April) reveals the mixed joys of “Liberty in the Philippines†after which a suitably foreboding ‘Prelude’ (Weird War Tales #4 (March/April 1972) captures the passive-panicked tension of daily routine whilst a potentially morale-shattering close shave is shared during an all-too-infrequent ‘Mail Call!’ (G.I. Combat #155, April/May)…

A thoughtful man of keen empathy and insight, Glanzman often offered readers a look at the real victims. ‘What Do They Know About War?’ (OAaW #244, April) sees peasant islanders trying to eke out a living, only to discover far too many similarities between Occupiers and Liberators, whilst the next issue focussed on the sailors’ jangling nerves and stomachs. ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the War!’ (#245, May) reveals what happened when DD479 was mistakenly declared destroyed and, thanks to an administrative iron curtain, found it impossible to refuel or take on food stores…

Cartoonist Jerry Boyle resurfaced in a ‘Comic Strip’ in OFF #138 (July/August) after which Glanzman produced one of the most powerful social statements in an era of tumultuous change.

Our Army at War #247 (July 1972) featured a tale based on decorated Pearl Harbor hero Doner Miller who saved lives, killed the enemy and won medals, but was not allowed to progress beyond the rank of shipboard domestic because of his skin. ‘Color Me Brave!’ was an excoriating attack on the U.S. Navy’s segregation policies and is as breathtaking and rousing now as it was then…

‘Ride the Baka’ (OAaW #248 August) revisits those constant near-miss moments sparked by suicide pilots after which Glanzman shares broken sleep in ‘A Nightmare from the Beginning’ (OFF #139, September/October) whilst ‘Another KunkÅ Warrior’ (OFF #140, November/December) sees marines taking an island and encountering warfare beyond their comprehension.

1973 began with a death-dipped nursery rhyme detailing ‘This is the Ship that War Built!’ (G.I.C #157 December 1972-January 1973) before ‘Buck Taylor’ (OFF #141 January/February) delivers an impromptu lecture on maritime military history. Glanzman struck an impassioned note for war-brides and lonely ships passing in the night with ‘The Islands Were Meant for Love!’ (Star Spangled War Stories #167 February)…

Terror turns to wonder when sailors encounter the ‘Portuguese Man of War’ (OAaW #256 August), a shore leave mugging is thwarted thanks to ‘Tailor-Mades’ (OFF #143 June/July) and letters home are necessarily self-censored in ‘The Sea is Calm… The Sky is Bright…’ (OAaW #257 June), but shipboard relationships remain complex and bewildering, as proved in ‘Who to Believe!’ (SSWS #171, July).

The strife of constant struggle comes to the fore in ‘The Kiyi’ (OAaW #258 July) and is seen from both sides when souvenir hunters try to take ‘The Thousand-Stitch-Belt’ (SSWS #172 August), but, as always, it’s non-combatants who truly pay the price, just like the native fishermen in ‘Accident…’ (OAaW #259, August).

Even the quietest, happiest moments can turn instantly fatal as the good-natured pilferers swiping fruit at a refuelling station discover in ‘King of the Hill’ (SSWS #174, October).

An unlikely tale of a kamikaze who survives his final flight but not his final fate, ‘Today is Tomorrow’ (OAaW #261, October) precedes a strident, wordless plea for understanding in ‘Where…?’ (OAaW #262 November 1973) before the sombre mood is briefly lifted with a tale of selfishness and sacrifice in ‘Rocco’s Roost’ from OAaW #265, February 1974.

The following issue provide both a gentle ‘Sam Glanzman’s War Diary’ covering down-time in “The Islands†and a brutal tale of mentorship and torches passed in ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’, after which a truly disturbing tale of what we now call gender identity and post-traumatic stress disorder is recounted in the tragedy of ‘Toro’ from the April/May Our Fighting Forces #148…

‘Moonglow’ from OAaW #267 (April 1974) reveals how quickly placid contemplation can turn to blazing conflagration, whilst – after a chilling, evocative ‘Sam Glanzman’s War Diary’ (OAaW #269 June) – ‘Lucky… Save Me!’ (OAaW #275, December 1974) shows how memories of unconditional love can offset the cruellest of injuries…

‘Heads I Win, Tails You Lose!’ (OAaW #281, June 1975) explores how both friend and foe alike can be addicted to risk, after which the next issue’s ‘I Am Old Glory…’ sardonically transposes a thoughtful veneration with the actualities of combat before ‘A Glance into Glanzman’ by Allan Asherman (Our Army at War #284, September 1975) takes a look at the author’s creative process.

Then it’s back to those sketchbooks and another peep ‘Between the Pages’ (OAaW #293, June 1976) before ‘Not Granted!’ (OAaW #298, November 1976) discloses every seaman’s most fervent wish…

Stories were coming at greater intervals at this time and it was clear that – editorially at least – the company was moving on to fresher fields. Glanzman, however, had saved his best till last as a stomach-churning visual essay displayed the force of tension sustained over months in ‘…And Fear Crippled Andy Payne’ (Sgt. Rock #304, May 1977) before an elegy to bravery and stupidity asked ‘Why?’ in Sgt. Rock #308 from September 1977.

And that was it for nearly a decade. Glanzman – a consummate professional – moved on to other ventures. He was, however, constantly asked about U.S.S. Stevens and eventually, nearly a decade later, returned to his spiritual stomping grounds in expanded tales of DD479: both in his graphic novel memoirs and comic strips.

The latter appeared in anthological black-&-white Marvel magazine Savage Tales (#6-8, spanning August to December 1986) under the umbrella title ‘Of War and Peace – Tales by Mas’.

First up was ‘The Trinity’ blending present with past to detail a shocking incident of a good man’s breaking point, whilst a lighter tone informed ‘In a Gentlemanly Way’, as Glanzman recalled the different means by which officers and swabbies showed their pride for their ships. ‘Rescued by Luck’ than concentrated on a saga of island survival for sailors whose ship had sunk…

Next comes the hauntingly powerful black-&-white tale of then and now entitled ‘Even Dead Birds Have Wings’ (created for the Dover Edition of A Sailor’s Story from 2015) after which a chronologically adrift yarn (from Sgt. Rock Special #1, October 1992) evokes potently elegiac feelings, describing an uncanny act of gallantry under fire and the ultimate fate of old heroes in ‘Home of the Brave’…

A few years ago, by popular – and editorial – demand, Glanzman returned to the U.S.S. Stevens for an old friend’s swan song series; providing new tales for each issue of DC’s anthological 6-issue miniseries Joe Kubert Presents (December 2012- May 2013).

More scattershot reminiscences than structured stories, ‘I REMEMBER: Dreams’ and ‘I REMEMBER: Squish Squash’recapitulate unforgettable moments seen through eyes at the sunset end of life; recalling giant storms and lost friends, imagining how distant families endured war and absence and, as always, balancing funny memories with the tragic, like that time when the stiff-necked new commander…

‘Snapshots’ continues the reverie, blending a veteran’s war stories with cherished times as a kid on the farm whilst ‘The Figurehead’ delves deeper into the character of Buck Taylor and his esoteric quest for seaborne nirvana…

Closing that last hurrah were ‘Back and Forth 1941-1944’ and ‘Back and Forth 1941-1945’: an encapsulating catalogue of war service as experienced by the creator, mixing facts, figures, memories and reactions to form a quiet tribute to all who served and all who never returned…

With the stories mostly told, the ‘Afterword’ by Allan Asherman details those heady days when he worked at DC Editorial, and Glanzman would unfailingly light up the offices by delivering his latest strips, after which this monolithic milestone offers a vast and stunningly detailed appendix of ‘Story Annotations’ by Jon B. Cooke.

This is a magnificent collection of comic stories based on real life and what is more fitting than to end it with ‘U.S.S. Stevens DD479’ (coloured by Frank M. Cuonzo & lettered by Thomas Mauer): one final, lyrical farewell from Glanzman to his comrades and the ship which still holds his heart after all these years…?

This is an extraordinary work. In unobtrusive little snippets, Glanzman challenged myths, prejudices and stereotypes – of morality, manhood, race, sexuality and gender – decades before anybody else in comics even thought to try.

He also brought an aura of authenticity to war stories which has never been equalled: eschewing melodrama, faux heroism, trumped-up angst and eye-catching glory-hounding to instead depict how “brothers in arms†really felt and acted and suffered and died.

Shockingly funny, painfully realistic and visually captivating, U.S.S. Stevens is phenomenal and magnificent: a masterpiece by one of the very best of “The Greatest Generationâ€. I waited 40 years for this and I couldn’t be happier: a sublimely insightful, affecting and rewarding graphic memoir every home, school and library should have and one every reader will return to over and over.

Artwork and text © 2015 Sam Glanzman. All other material © 2015 its respective creators.