By Crockett Johnson (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-709-3 (HB)

This is one of those rare books worthy of two reviews. So, if you’re in a hurry…

Buy Barnaby now – it’s one of the five best comic strips of all time and this superb hardcover compilation has lots of fascinating extras. If you harbour any yearnings for the lost joys of childish wonder and the suspicious glee in catching out adults trying to pull a fast one, you would be crazy to miss this book…

However, if you’re still here and need a little more time to decide…

Today’s newspapers have precious few continuity drama or adventure strips. Indeed, if a paper has any strips – as opposed to single panel editorial cartoons – chances are they will be of the episodic variety typified by Jim Davis’ Garfield or Scott Adams’ Dilbert.

You might describe these as single-idea pieces with a set-up, delivery and punch-line, all rendered in a sparse, pared-down-to-basics drawing style. In that they’re nothing new and there’s nothing wrong any of that ilk on their own terms.

Narrative impetus comes from the unchanging characters themselves, and a building of gag-upon-gag in extended themes. The advantage to newspapers is obvious. If you like a strip it encourages you to buy the paper. If you miss a day or two, you can return fresh at any time having, in real terms, missed nothing.

Such was not always the case, especially in America. Once upon a time the daily “funnies†– comedic or otherwise – were crucial circulation builders and preservers, with lush, lavish and magnificently rendered fantasies or romances rubbing shoulders with thrilling, moody masterpieces of crime, war, sci-fi and everyday melodrama. Even the legion of humour strips actively strived to maintain an avid, devoted following.

And eventually there was Barnaby, which in so many ways bridged the gap between then and now.

On April 20th 1942, with America at war for the second time in 25 years, the liberal New York tabloid PM began running a new, sweet little kids’ strip which was also the most whimsically addicting, socially seditious and ferociously smart satire since the creation of Al Capp’s Li’l Abner – another utter innocent left to the mercy of venal and scurrilous worldly influences…

The outlandish 4-panel daily, by Crockett Johnson, was the product of a perfectionist who didn’t particularly care for comics, but who – according to celebrated strip historian Ron Goulart – just wanted steady employment…

David Johnson Leisk (October 20th 1906-July 11th 1975) was an ardent socialist, passionate anti-fascist, gifted artisan and brilliant designer who spent much of his working life as a commercial artist, Editor and Art Director. Born in New York City and raised in the outer wilds of Queens when it was still semi-rural – very near the slag heaps which would eventually house two New York World’s Fairs in Flushing Meadows – “Dave†studied art at Cooper Union (for the Advancement of Science and Art) and New York University before leaving early to support his widowed mother. This entailed embarking upon a hand-to-mouth career drawing and constructing department-store advertising.

He supplemented his income with occasional cartoons to magazines such as Collier’s before becoming an Art Editor at magazine publisher McGraw-Hill. He also began producing a moderately successful, “silent†strip called The Little Man with the Eyes.

Johnson had divorced his first wife in 1939 and moved out of the city to Connecticut, sharing an ocean-side home with student (and eventual bride) Ruth Krauss, always looking to create that steady something when, almost by accident, he devised a masterpiece of comics narrative. However, if his friend Charles Martin hadn’t seen a prototype Barnaby half-page lying around the house, the series might never have existed…

Happily, Martin hijacked the sample and parlayed it into a regular feature in prestigious highbrow leftist tabloid PM simply by showing the scrap to the paper’s Comics Editor Hannah Baker. Among her other finds was a strip by a cartoonist dubbed Dr. Seuss which would run contiguously in the same publication. Despite Johnson’s initial reticence, within a year Barnaby had become the new darling of the intelligentsia…

Soon there were book collections, talk of a Radio show (in 1946 it was adapted as a stage play), a quarterly magazine and rave reviews in Time, Newsweek and Life. The small but rabid fan-base ranged from politicians and the smart set such as President and First Lady Roosevelt, Vice-President Henry Wallace, Rockwell Kent, William Rose Benet and Lois Untermeyer to cool celebrities such as Duke Ellington, Dorothy Parker, W. C. Fields and even legendary New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Of course, the last two might only have been checking the paper because the undisputed, unsavoury star of the strip was a scurrilous if fanciful amalgam of them both…

Not since George Herriman’s Krazy Kat had a piece of popular culture so infiltrated the halls of the mighty, whilst largely passing way over the heads of the masses and without troubling the Funnies sections of big circulation papers. Over its 10-year run (April 1942 to February 1952), Barnaby was only syndicated to 64 papers nationally, with a combined circulation of just over five and a half million, but it kept Crockett (a childhood nickname) and Ruth in relative comfort whilst America’s Great and Good constantly agitated on the kid’s behalf.

What more do you need to know?

One dark night a little boy wishes for a Fairy Godmother and something strange and disreputable falls in through his window…

Barnaby Baxter is a smart, ingenuous, scrupulously honest and rather literal pre-schooler (4 years old to you) and his ardent wish is to be an Air Raid Warden like his dad. Instead, he is “adopted†by a short, portly, pompous, mildly unsavoury and wholly discreditable windbag with pink pixie wings.

Jackeen J. O’Malley, card carrying-member of the Elves, Gnomes, Leprechauns and Little Men’s Chowder and Marching Society – although he hasn’t paid his dues in years – unceremoniously installs himself as the lad’s Fairy Godfather. A lazier, more self-aggrandizing, mooching old glutton and probable soak (he certainly frequents taverns but only ever raids the Baxter’s icebox, pantry and humidor, never their drinks cabinet…) could not be found anywhere.

Due more to intransigence than evidence – there’s always plenty of physical proof, debris and fallout whenever O’Malley has been around – Barnaby’s mum and dad adamantly refuse to believe in the insalubrious sprite, whose continued presence hopelessly complicates the sweet boy’s life.

The poor doting parents’ abiding fear is that Barnaby is afflicted with Too Much Imagination…

At the end of the first volume O’Malley implausibly – and almost overnight – became an unseen and reclusive public Man of the Hour, preposterously translating that cachet into a political career by accidentally becoming a patsy for a vast and corrupt political machine. In even more unlikely circumstances O’Malley is then elected to Congress – which somehow doesn’t seem so fantastic any more…

This strand gave staunchly socialist cynic Johnson ample opportunity to ferociously lampoon the electoral system, the pundits and even the public. As usual Barnaby’s parents had to perpetually put down their boy: assertively assuring him that the O’Malley the grown-ups had elected was not a fat little man with pink wings…

Despite looking like a fraud – he’s almost never seen using his magic and always has one of Dad’s stolen panatela cigars as a substitute wand – J. J. O’Malley is the real deal: he’s just incredibly lazy, greedy, arrogant and inept. He does sort of grant Barnaby’s wishes though… but never in ways that might be wished for…

Once O’Malley has his foot in the door – or rather through the bedroom window – a succession of bizarre characters start sporadically turning up to baffle and bewilder Barnaby and Jane Shultz, the sensible little girl next door.

Even the boy’ new dog Gorgon is a remarkable oddity. The pooch can talk – but never when adults are around, and only then with such overwhelming dullness that everybody listening wishes him as mute as every other mutt…

The mythical oddballs and irregulars include timid ghost Gus, Atlas the Giant (a 2-foot tall, pint-sized colossus who is not that impressive until he gets out his slide-rule to demonstrate that he was, in truth, a mental Giant) and LauncelotMcSnoyd, an invisible Leprechaun and O’Malley’s personal gadfly: always offering harsh, ribald home truths and counterpoints to the Godfather’s self-laudatory pronouncements…

Johnson continually expanded his gently bizarre cast of gremlins, ogres, ghosts, policemen, Bankers, crooks, financiers and stranger personages – all of whom can see O’Malley – but the unyieldingly faithful little lad’s parents are always too busy and too certain the Fairy Godfather and all his ilk are unhealthy, unwanted, juvenile fabrications.

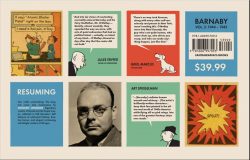

This second stupendous collection – available as a landscape hardback and in digital formats – opens with a hearty appreciation from Jules Feiffer in the Foreword before cartoonist, biographer and historian R. C. Harvey provides a critical appraisal in ‘Barnaby and the Power of Imagination’. The captivating yarn-spinning commences next, taking us from January 1st 1944 to December 31st 1945.

There’s even more elucidatory content at the back after all those magic-filled pictures too, as education scholar and Professor of English Philip Nel provides a fact-filled, scene-setting, picture-packed ‘Afterword: O’Malley Takes Flight’and Max Lerner’s 1943 PM promo feature ‘Barnaby’s Progress’ is reprinted in full.

Nel also supplies strip-by-strip commentary and background in ‘The Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, and Little Men’s Chowder & Marching Society: A Handy Pocket Guide’…

However, what we all love is comics so let’s jump right in as the obese elf gets caught up in exhibiting his miniscule expertise in ‘The Manly Art of Self-Defense’ (running from 28th December 1943 to 19th January 1944), and follows Mr. Baxter’s purchase of a few items of exercise equipment.

Always with an eye to a fast buck, O’Malley organises a prize fight between poor gentle Gus and the obstreperous Brooklyn Leprechaun, all whilst delaying his long overdue return to the Capitol. The godfather is expert in delay and obfuscation but eventually, in a concatenation of curious circumstances, the Congressman buckles under pressure from both his human and fairy-folk constituents to push through a new hydroelectric project – in actuality two vastly different ones – and wings off to begin the process of funding ‘The O’Malley Dam’ (20th January – 22nd April)…

As the political bandwagon gets rolling, further hindered by Mr. Baxter and Barnaby visiting the Congressman’s never-occupied office in Washington DC, the flighty, easily distracted O’Malley takes it upon himself to inscribe the natural history of his people in ‘Pixie Anthropology’ (24th April-18th May), even as, back home, the Big Fight gets nearer and poor Gus continues to wilt under his punishing training regimen…

‘Mr. O’Malley, Efficiency Expert’ (19th May to 8th June), sees the Fairy Fool step in when overwork and worry laid Mr. Baxter low. The factory manager is pilloried by concerns over production targets, but whilst he is remanded to his sickbed, the flying figment busily “fixes†the crisis for him…

During that riotous sequence another oddball was introduced in the diminutive form of Gridley the Salamander: a “Fire Pixey†who can’t raise a spark, even if copiously supplied with matches and gasoline…

The under-worked winged windbag is a master of manipulation and ‘O’Malley and the Buried Treasure’ (9th June – 7thSeptember) has the airborne oaf inveigling invitations for the Baxters to the beachside cottage owned by Jane’s aunt. Once there, it isn’t long before avaricious imagination and a couple of old coins spawn a rabid goldrush amongst the adults who really should know better. This extended vacation also sees the first appearance of moisture-averse sovereign of the seas Davy Jones…

Whilst the Congressman busily avoids work, his seat vanishes during boundary reorganisation, but – ever-undaunted – the pixilated political animal soldiers on, outrageously campaigning in the then-ongoing Presidential Election throughout the cruelly hilarious ‘O’Malley for Dewey’ (8th September – 8th November 1944)…

Newspaper strips always celebrated seasonal events and, after the wry satire of the race for power, whacky whimsy is highlighted with the advent of ‘Cousin Myles O’Malley’ (9th – 24th November). The puny Puritan pixie had come over on the Mayflower and is still trying to catch a turkey for his very first Thanksgiving Dinner. Naturally his take-charge, thoroughly modern relative is a huge (dis)advantage to his ongoing quest…

With Christmas fast approaching, an injudicious expression from Ma Baxter regarding a fur wrap sets Barnaby and his Fairy guardian on the trail of the fabled and fabulous, ferocious ermine beast and debuts ‘The O’Malley Fur Trading Post’(25th November 1944 to 27th January 1945).

Although legendary and mythical gnomish huntsman J. P. Orion fails to deliver, an unlucky band of fur thieves fall into the hunters’ traps and discover their latest haul missing. Before long, poor Mr. Baxter is looking at the chilling prospect of jail time for receiving stolen property…

With the global conflict clearly drawing to a close, Johnson threw himself into the debate of what the post-War world would be like. In a swingeing attack on the financial system and the greedy gullibility of professional money men, Barnaby – and most especially his conniving godfather – almost shatter the American commercial world in a cunning fable entitled ‘J.J. O’Malley, Wizard of Wall Street’ (29th January – 26th May)…

With America still reeling, the ever-unfolding hilarity offers an arcane twist as Mr. Baxter suffers more than the usual degree of personal humiliation and confusion when he takes Barnaby, Gorgon and Jane for a short walk and loses them in the littlest woods in America.

They have of course been led astray by O’Malley who accidentally dumps them on ‘Emmylou Schwartz, Licensed Witchcraft Practitioner’ (28th May – 3rd July). She has been in a very bad mood ever since the Salem Witch Trials…

As a result of this latest unhappy encounter and a shameful incident with a black cat, the dogmatic dog is hexed and becomes ‘Tongue-Tied Gorgon’ (4th – 10th July)… not that most people could ever tell…

When Barnaby’s Aunt Minerva writes a bestseller, O’Malley feels constrained to guide her budding career in ‘Belles Lettres’ (11th July – 17th August). The obnoxious elf is a little less keen when he discovers it’s only a cookbook, but perks up when it leads to Minerva being offered a newspaper column. Being an expert in this field too, O’Malley continues his behind-the-scenes support amidst ‘The Fourth Estate’ (18th August – 8th September), renewing his old acquaintance with impishly literal Printers Devil Shrdlu…

Immune to O’Malley’s best efforts, Minerva remains a success and is soon looking for her own place. In ‘Real Estate’(10th September -10th October), Barnaby is helpless to prevent poor Gus being used by the godfather as a ghostly goad to convince a spiritualism-obsessed landlady to let to his aunt rather than a brace of conmen…

A perfect indication of the wry humour that peppered the feature can be seen in ‘Party Invitations’ – which ran from 11thto 20th October – as O’Malley attempts to supersede the usual turkey-and-fixin’s feast with a fashionable venison banquet – even though he can’t catch a deer and won’t be cooking it once it’s been butchered…

Congruent with that is the introduction of erudite aborigine ‘Howard the Sigahstaw Indian‘ (22nd October – 23rdNovember) – who was just as inept in the hunting traditions of his forefathers – after which the festive preparations continue with ‘O’Malley’s Christmas List’ (24th November – 15th December) wherein the always-generous godfather discovers the miracle of store credit and goes gift shopping for everybody.

Never one to concentrate for long, he is briefly distracted by a guessing competition in ‘Bean-Counting’ (8th – 15thDecember): the prize of a home movie camera being the ideal gift for young Barnaby before this parade of monochrome cartoon marvels concludes with the dryly hilarious saga of ‘The Hangue Dogfood Telephone Quiz Program’ (17thDecember 1945-1st January 1946) wherein Gorgon’s reluctant answers to an advertising promotion again threaten to hurl the entire American business world into chaos…

Intellectually raucous, riotously, sublimely surreal and adorably absurd, the untrammelled, razor-sharp whimsy of the strip is instantly captivating, and the laconic charm of the writing is well-nigh irresistible, but the lasting legacy of this ground-breaking strip is the clean sparse line-work that reduces images to almost technical drawings, unwavering line-weights and solid swathes of black that define space and depth by practically eliminating it, without ever obscuring the fluid warmth and humanity of the characters. Almost every modern strip cartoon follows the principles laid down here by a man who purportedly disliked the medium…

The major difference between then and now should also be noted, however.

Johnson despised doing shoddy work, or short-changing his audience. On average, each of his daily encounters – always self-contained – built on the previous episode without needing to re-reference it, and contained three to four times as much text as its contemporaries. It’s a sign of the author’s ability that the extra wordage was never unnecessary, and often uniquely readable, blending storybook clarity, the snappy pace of “Screwball†comedy films and the contemporary rhythms and idiom of authors such as Damon Runyan and Dashiel Hammett.

He managed this miracle by typesetting the dialogue and pasting up the strips himself – primarily in Futura Medium Italic but with effective forays into other fonts for dramatic and comedic effect.

No sticky-beaked educational vigilante could claim Barnaby harmed children’s reading abilities by confusing the tykes with non-standard letter-forms (a charge levelled at comics as late as the turn of this century), and his efforts also allowed him to maintain an easy, elegant, effective balance of black and white, making the deliciously diagrammatic art light, airy and implausibly fresh and accessible.

During 1946-1947, Johnson surrendered the strip to friends as he pursued a career illustrating children’s books such as Constance J. Foster’s This Rich World: The Story of Money, but eventually he returned, crafting more magic until he retired Barnaby in 1952 to concentrate on books.

When Ruth graduated, she became a successful children’s writer and they collaborated on four tomes, The Carrot Seed (1945), How to Make an Earthquake, Is This You? and The Happy Egg, but these days Crockett Johnson is best known for his seven “Harold†books which began in 1955 with the captivating Harold and the Purple Crayon.

During a global war with heroes and villains aplenty, where no comic page could top the daily headlines for thrills, drama and heartbreak, this feature was an absolute panacea to the horrors without ever ignoring or escaping them. The entire glorious confection that is Barnaby is all about our relationship with imagination. This is not a strip about childhood fantasy. The theme here, beloved by both parents and children alike, is that grown-ups don’t listen to kids enough, and that they certainly don’t know everything.

For far too long Barnaby was a lost masterpiece. It is influential, ground-breaking and a shining classic of the form. You are all the poorer for not knowing it, and should move mountains to change that situation. I’m not kidding.

Liberally illustrated throughout with sketches, roughs, photos and advertising materials as well as Credits, Thank Yous and a brief biography of Johnson, this big hardback book of joy is a an indispensable addition to all bookshelves and collections – most especially yours…

Barnaby vol. 2 and all Barnaby images © 2014 the Estate of Ruth Krauss. Supplemental material © 2014 its respective creators and owners.