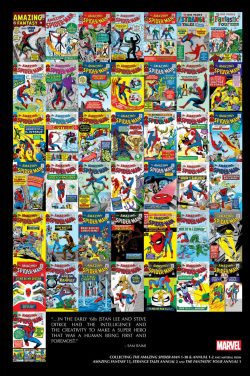

By Stan Lee & Steve Ditko with Jack Kirby, Art Simek, Sam Rosen, Jon D’Agostino, John Duffy, Ray Holloway & various (MARVEL)

ISBN: 978-1-3029-4563-3 (HB/Digital edition)

Win’s Christmas Gift Recommendation: Utter Entertainment Perfection… 10/10

The Amazing Spider-Man celebrated his 60th anniversary in 2022. However, I’m one of those radicals who feel that 1963 was when he was really born, so let’s close this year with one last acknowledgement of that…

Marvel is often termed “the House that Jack Built” and King Kirby’s contributions are undeniable and inescapable in the creation of a new kind of comic book storytelling. However, there was another unique visionary toiling at Atlas-Comics-as-was: one whose creativity and philosophy seemed diametrically opposed to the bludgeoning power, vast imaginative scope and clean, gleaming futurism that resulted from Kirby’s ever-expanding search for the external and infinite.

Steve Ditko was quiet and unassuming, diffident to the point of invisibility, but his work was both subtle and striking: innovative and meticulously polished. Always questing for affirming detail, he ever explored the man within. He saw heroism and humour and ultimate evil all contained within the frail but noble confines of humanity. His drawing could be oddly disquieting… and, when he wanted, decidedly creepy.

Crafting extremely well-received monster and mystery tales for and with Stan Lee, Ditko had been rewarded with his own title. Amazing Adventures/Amazing Adult Fantasy featured a subtler brand of yarn than Rampaging Aliens and Furry Underpants Monsters: an ilk which, though individually entertaining, had been slowly losing traction in the world of comics ever since National/DC had successfully reintroduced costumed heroes.

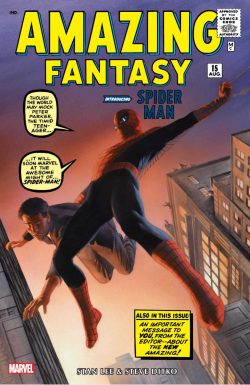

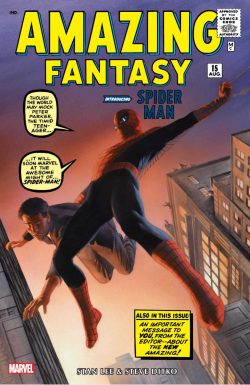

Lee & Kirby had responded with The Fantastic Four and so-ahead-of-its-time Incredible Hulk, but there was no indication of the renaissance ahead when officially just-cancelled Amazing Fantasy featured a brand new and rather eerie adventure character…

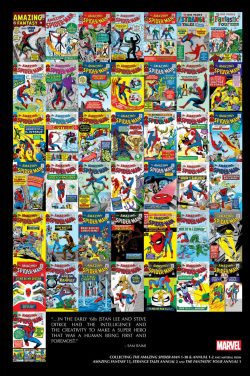

This compelling compilation re-presents the rise of the wallcrawler as originally seen in Amazing Fantasy #15, The Amazing Spider-Man #1-38, Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1 & 2 plus material from Strange Tales Annual #2 and Fantastic Four Annual #2 collectively spanning cover-dates August 1962-July 1966). It is lettered throughout by unsung superstars Sam Rosen, Art Simek, Jon D’Agostino, John Duffy and Ray Holloway and sadly an anonymous band of colourists. As well as a monolithic assortment of nostalgic treats at the back, this mammoth tome is dotted throughout with recycled Introductions from Stan Lee, taken from the first four Marvel Masterworks editions devoted to the webspinner and includes editorial announcements and the ‘Spider’s Web’ newsletter pages for each original issue to enhance that wayback machine experience…

The wonderment came and concluded in 11 captivating pages: ‘Spider-Man!’ tells the parable of smart but alienated Peter Parker, a kid bitten by a radioactive spider on a high school science trip. Discovering he has developed arachnid abilities – which he augments with his own natural engineering genius – he does what any lonely, geeky nerd would do when given such a gift – he tries to cash in for girls, fame and money.

Creating a costume to hide his identity in case he makes a fool of himself, Parker becomes a minor celebrity – and a vain, self-important one. To his eternal regret, when a thief flees past, he doesn’t lift a finger to stop him, only to find when he returns home that his Uncle Ben has been murdered.

Crazy for vengeance, Parker stalks the assailant who made his beloved Aunt May a widow and killed the only father he had ever known, only to find that it is the felon he couldn’t be bothered with. Since his irresponsibility led to the death of the man who raised him, the boy swears to always use his powers to help others…

It wasn’t a new story, but the setting was one familiar to every kid reading it and the artwork was downright spooky. This wasn’t the gleaming high-tech world of moon-rockets, giant monsters and flying cars – this stuff could happen to anybody…

Amazing Fantasy #15 came out the same month as Tales to Astonish #35 (cover-dated September 1962) – the first to feature the Astonishing Ant-Man in costumed capers, but it was also the last issue of Ditko’s Amazing playground. With this volume you’ll find the ‘Fan Page – Important Announcement from the Editor!’ that completely misled fans as to what would happen next…

The tragic last-ditch tale struck a chord with readers and by Christmas a new comic book superstar was ready to launch in his own title, and Ditko eager to show what he could do with his first returning character since the demise of Charlton action hero Captain Atom.

Holding on to the “Amazing” prefix memories, bi-monthly Amazing Spider-Man #1 arrived with a March 1963 cover-date and two complete stories. It also prominently featured the Fantastic Four and took the readership by storm. The opening tale, again simply entitled ‘Spider-Man!’, recapitulated the origin whilst adding a brilliant twist to the conventional mix.

Now the wall-crawling hero was feared and reviled by the general public thanks in no small part to newspaper magnate J. Jonah Jameson who pilloried the adventurer from spite and for profit. With time-honoured comic book irony, Spider-Man then had to save Jameson’s astronaut son John from a faulty space capsule in extremely low orbit…

Second yarn ‘Vs the Chameleon!’ finds the cash-strapped kid trying to force his way onto the roster – and payroll – of the FF whilst elsewhere a spy perfectly impersonates the webspinner to steal military secrets: a stunning example of the high-strung, antagonistic crossovers and cameos that so startled jaded kids of the early 1960s. Heroes just didn’t act like that and they certainly didn’t speak directly to the fans as in ‘A Personal Message from Spider-Man’ that’s reprinted here…

With his second issue, our new champion began a meteoric rise in quality and innovative storytelling. ‘Duel to the Death with the Vulture!’ catches Parker chasing a flying thief as much for profit as justice. Desperate to help his aunt make ends meet, Spider-Man starts taking photos of his cases to sell to Jameson’s Daily Bugle, making his personal gadfly his sole means of support.

Matching his deft comedy and moody soap-operatic melodrama, Ditko’s action sequences were imaginative and magnificently visceral, with odd angle shots and quirky, mis-balanced poses adding a vertiginous sense of unease to fight scenes. But crime wasn’t the only threat to the world and Spider-Man was just as (un)comfortable battling “aliens” in ‘The Uncanny Threat of the Terrible Tinkerer!’

Amazing Spider-Man #3 introduced possibly the apprentice hero’s greatest enemy in ‘Versus Doctor Octopus’: a full-length saga wherein a dedicated scientist survives an atomic accident only to discover his self-designed mechanical “waldoes”/tentacles have permanently grafted to his body. Power-mad, Otto Octavius initially thrashes Spider-Man, sending the lad into a depression until an impromptu pep-talk from Human Torch Johnny Storm galvanises the arachnid to one of his greatest victories. Also included is a stunning ‘Special Surprise Bonus Spider-Man Pin-up Page!’…

‘Nothing Can Stop… The Sandman!’ was another instant classic wherein a common thug gains the power to transform to sand (in another pesky nuclear snafu), invades Parker’s school, and must be stopped at all costs, after which1963’s Strange Tales Annual #2 featured ‘The Human Torch on the Trail of the Amazing Spider-Man!’

This terrific romp from Lee & Kirby with Ditko inking details how the wallcrawler is framed by international art thief The Fox, instigating an early “Marvel Misunderstanding Clash” and is followed by short story ‘The Fabulous Fantastic Four meet Spider-Man!’: re-examining in an extended re-interpretation that first meeting from the premiere issue of the wallcrawler’s own comic and taken from Fantastic Four Annual #1.

With Ditko on pencils and inks again, Amazing Spider-Man #5 saw the webspinner ‘Marked for Destruction by Dr. Doom!’ – not so much winning as surviving his battle against the deadliest man on Earth. Presumably he didn’t mind too much, as this marked the transition from bi-monthly to monthly status for the series. In this tale Parker’s nemesis, jock bully Flash Thompson, first displays depths beyond the usual in contemporary comicbooks, beginning one of the best love/hate buddy relationships in popular literature…

Eventual mentor Dr. Curtis Connors debuts in #6 when Spidey comes ‘Face-to-face With… The Lizard!’ as the wallcrawler fights far from the concrete canyon comfort zone of New York – specifically in the murky Florida Everglades. Parker was back in the Big Apple in #7 to breathtakingly tackle ‘The Return of the Vulture’ in a full-length action extravaganza.

Fun and youthful hi-jinks were a signature feature of the series, as was Parker’s budding romance with “older woman” Betty Brant, Jameson’s secretary/PA at the Bugle. Youthful exuberance was the underlying drive in #8’s lead tale ‘The Living Brain!’ wherein an ambulatory robot calculator is tasked with exposing Spider-Man’s secret identity before running amok at beleaguered Midtown High, just as Parker is finally beating the stuffings out of bully Flash Thompson.

This 17-page triumph was accompanied by ‘Spiderman Tackles the Torch!’: a 6-page vignette drawn by Kirby and inked by Ditko, wherein a boisterous wallcrawler gate-crashes a beach party thrown by the flaming hero’s girlfriend – with suitably explosive consequences…

Amazing Spider-Man #9 is a qualitative step-up in dramatic terms, as Aunt May is revealed to be chronically ill and adding to Parker’s financial woes. Action is supplied by ‘The Man Called Electro!’ – an accidental super-criminal with grand aspirations.

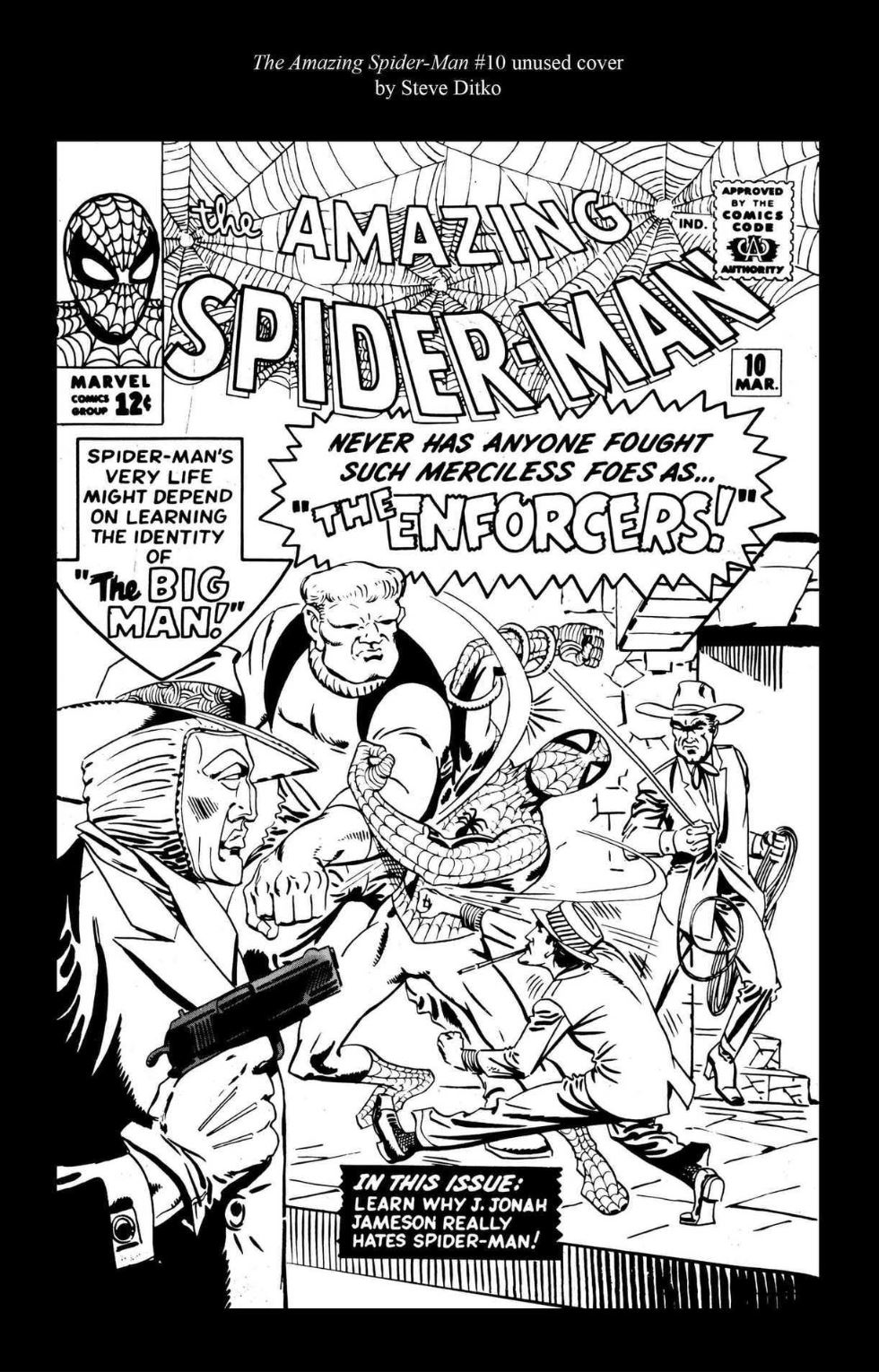

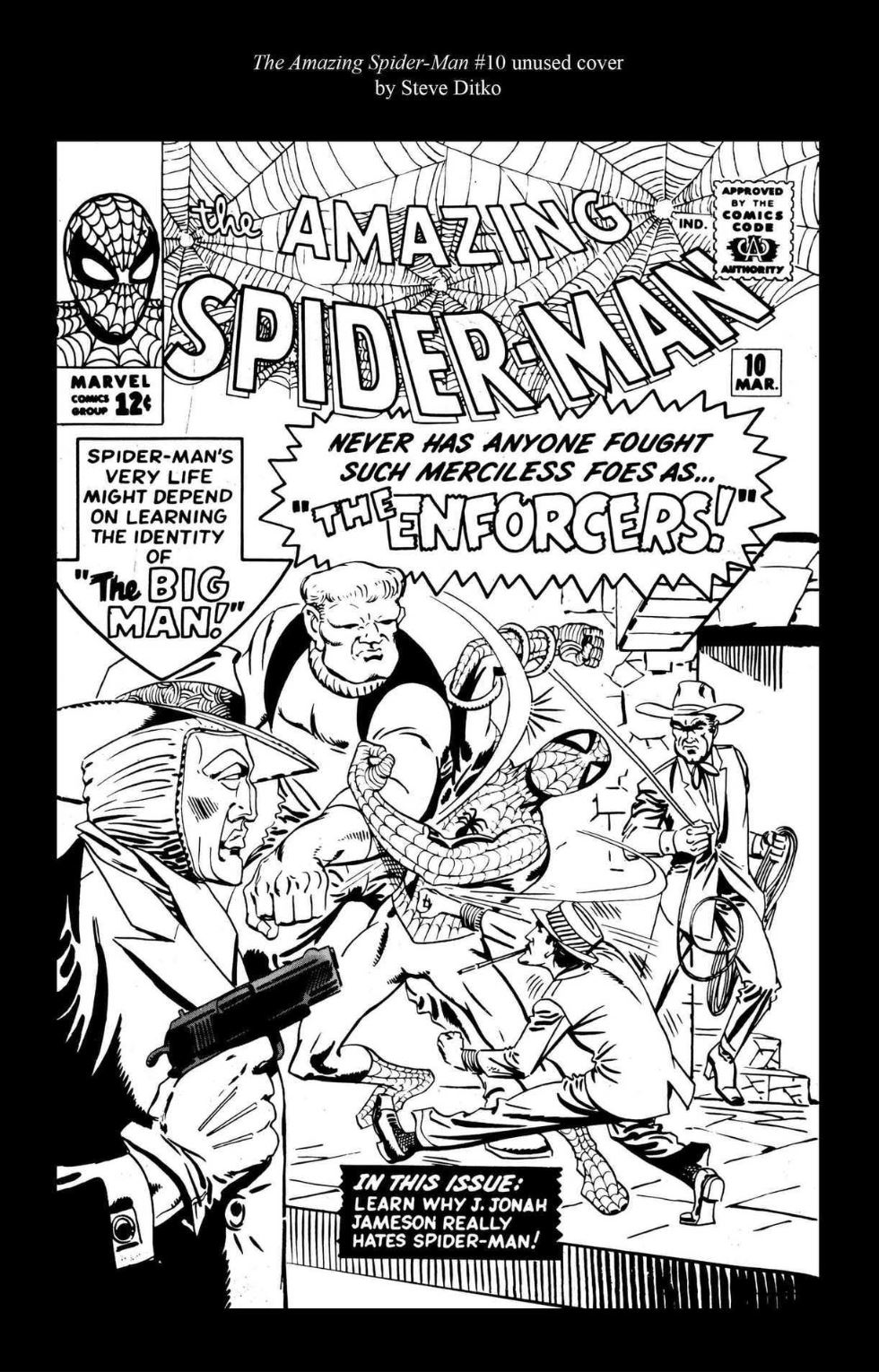

Spider-Man was always a loner, never far from the streets and small-scale-crime, and with this tale – wherein he also quells a prison riot single handed – Ditko’s preference for tales of gangersterism starts to proliferate: a predilection confirmed in #10’s ‘The Enforcers!’ (AKA Fancy Dan, Montana and The Ox). This is a classy mystery with a masked mastermind known as The Big Man, using a position of trust to organise all New York mobs into one unbeatable army against decency.

Longer plot-strands are also introduced as Betty mysteriously vanishes, although most fans remember this one for the spectacularly climactic 7-page fight scene in an underworld chop-shop that has still never been beaten for action-choreography.

The wonderment intensifies (after a Lee Introduction) with a magical 2-part yarn. ‘Turning Point’ and ‘Unmasked by Dr. Octopus!’ sees the lethally deranged and deformed scientist return and the disclosure of a long-hidden secret which had haunted Parker’s girlfriend Betty Brant for years.

The dark, tragedy-filled tale of extortion and excoriating tension stretches from Philadelphia to the Bronx Zoo and cannily tempers trenchant melodrama with spectacular fight scenes in unusual and exotic locations, before culminating in a truly staggering super-powered duel as only Ditko could orchestrate it.

A new super-foe premiered in Amazing Spider-Man #13 with ‘The Menace of Mysterio!’ as publisher J. Jonah Jameson hires a seemingly eldritch bounty-hunter to capture Spider-Man before eventually letting slip his own dark criminal agenda, whilst #14 offers an absolute milestone in the series as a hidden criminal mastermind manipulates a Hollywood studio into making a movie about the wall-crawler. Even with guest-star opposition The Enforcers and Incredible Hulk, ‘The Grotesque Adventure of the Green Goblin’ is most notable for introducing Spider-Man’s most perfidious and flamboyant enemy.

Jungle superman and thrill-junkie (and modern movie star!) ‘Kraven the Hunter!’ makes Spidey his intended prey at the behest of embittered former-foe the Chameleon in #15, and promptly pops up again in the first Amazing Spider-Man Annual (1964) that follows.

A timeless landmark and still magnificently thrilling battle, tale, the ‘Sinister Six’ begins after a band of villains comprising Electro, Kraven, Mysterio, Sandman, Vulture and Dr Octopus abduct May Parker and Betty, forcing Spider-Man to confront them without his powers – lost in a guilt-fuelled panic attack.

A staggeringly compelling Fights ‘n’ Tights saga, this influential tale featured cameos (or, more honestly, product placement segments) by every other extant hero of the budding Marvel universe.

Also included in the colossal comic compendium were special feature pages on ‘The Secrets of Spider-Man!’ and comedic short ‘How Stan Lee and Steve Ditko Created Spider-Man’ plus a gallery of pin-up pages featuring ‘Spider-Man’s Most Famous Foes!’ – (the Burglar, Chameleon, Vulture, Terrible Tinkerer, Dr. Octopus, Sandman, Doctor Doom, The Lizard, Living Brain, Electro, The Enforcers, Mysterio, Green Goblin and Kraven the Hunter) – as well as pin-ups of Betty and Jonah, Parker’s classmates and house, and even heroic guest stars…

Amazing Spider-Man #16 extended that circle of friends and foes as the webslinger battles The Ringmaster and Circus of Evil, meeting a fellow loner hero in a dazzling ‘Duel with Daredevil’. This delightful diversion segued into an ambitious 3-part saga, beginning in Amazing Spider-Man #17 wherein our rapidly-maturing hero touches emotional bottom before rising to triumphant victory over all manner of enemies in ‘The Return of the Green Goblin!’, as the wallcrawler endures renewed print assaults in the Daily Bugle from its rabid publisher just as his enigmatic veridian archvillain opened a sustained war of nerves and attrition, using The Enforcers, Sandman and an army of thugs to publicly humiliate the hero. To exacerbate matters, Aunt May’s health took a drastic downward turn…

Resuming with ‘The End of Spider-Man!’ and explosively concluding in triumphal big finish ‘Spidey Strikes Back!’ – featuring a turbulent team-up with friendly rival the Human Torch – this extended tale proved fans were ready for every kind of narrative experiment (single issue or two stories per issue were still the norm in 1964) and Stan & Steve were more than happy to try anything.

With ‘The Coming of the Scorpion!’, Jameson let his obsessive hatred for the cocky kid crusader get the better of him: hiring scientist Farley Stillwell to endow a private detective with insectoid-based superpowers. Sadly, the process drove mercenary Mac Gargan mad before he could capture Spidey, leaving the webspinner with yet another lethally dangerous meta-menace to deal with…

That issue closed with pin-up of ‘Peter Parker and Ol’ Webhead’ before #21 highlights a hilarious love triangle in ‘Where Flies the Beetle’ as the Torch’s girlfriend uses Peter Parker to make the flaming hero jealous. Unfortunately, the Beetle – a villain with high-tech insect-themed armour – is simultaneously stalking Doris Evans as bait for a trap. As ever, Spider-Man was simply in the wrong place at the right time, resulting in a spectacular fight-fest.

This issue also offers a stunning and much reprinted Ditko Marvel Masterwork Pin-up of ‘Spider-Man’ before ASM #22 preeeeeeeesents… ‘The Clown, and his Masters of Menace!’: affording a return engagement for the Circus of Crime with splendidly outré action and a lot of hearty laughs provided by increasingly irreplaceable supporting stars Aunt May, Betty Brant and Jameson, before #23 delivers a superb thriller blending the mundane mobster and thugs that Ditko loved to depict with the more outlandish threat of a supervillain attempting to take over all the city’s gangs.

‘The Goblin and the Gangsters’ is both moody and explosive, the supervillain’s plot foiled by a cunning competitor and the driven hero’s ceaseless energy, and this tale is complemented by a Ditko Marvel Masterwork Pin-up of ‘Spidey’ that amazingly features all the supporting cast and every extant villain in his rogue’s gallery…

Another recurring plot strand debuted in #24, as a dark brooding tale had the troubled boy question his own sanity in ‘Spider-Man Goes Mad!’. The sinister stunner sees a clearly delusional wallcrawler seeking psychiatric help, but there’s more to the matter than simple insanity, as an insidious old foe unexpectedly returns, employing psychological warfare…

Amazing Spider-Man #25 once more sees our obsessed publisher take matters into his own hands. ‘Captured by J. Jonah Jameson!’ introduces Professor Smythe – whose dynasty of robotic Spider-Slayers would bedevil the webslinger for years to come – hired to remove Spider-Man for good.

Issues #26 & 27 comprise a captivating 2-part mystery and deadly duel between Green Goblin and an enigmatic new criminal. ‘The Man in the Crime-Master’s Mask!’ and ‘Bring Back my Goblin to Me!’ together form a perfect arachnid epic, with soap-opera melodrama and screwball comedy leavening tense crimebusting thrills and all-out action.

ASM #28’s ‘The Menace of the Molten Man!’ is a tale of science gone bad and remains remarkable today not only for spectacular action sequences – and possibly the most striking Spider-Man cover ever produced – but also as the story in which Peter Parker graduates from High School.

Ditko was on peak form and fast enough to handle two monthly strips. At this time he was also blowing away audiences with another oddly tangential superhero. Two extremely disparate crusaders met in ‘The Wondrous World of Dr. Strange!’: lead story in the second super-sized Spider-Man Annual (released in October 1965 and filled out with vintage Spidey classics). The entrancing fable unforgettably introduced the Amazing Arachnid to arcane other realities as he teamed up with the Master of the Mystic Arts to battle power-crazed mage Xandu in a phantasmagorical, dimension-hopping masterpiece involving ensorcelled zombie thugs and the stolen Wand of Watoomb. After this, it was clear that Spider-Man could work in any milieu and nothing could hold him back…

Also from that immensely impressive landmark are more Ditko pin-ups via ‘A Gallery of Spider-Man’s Most Famous Foes’ – highlighting such nefarious ne’er-do-wells as The Circus of Crime, The Scorpion, The Beetle, Jonah’s Robot and The Crime-Master.

Back in the ever-more popular monthly mag, ASM #29 warned ‘Never Step on a Scorpion!’ as the lab-made larcenous lunatic returned, seeking vengeance on not just the webspinner but also Jameson for turning a disreputable private eye into a super-powered monster…

Issue #30’s off-beat crime-caper then cannily sowed seeds for future masterpieces as ‘The Claws of the Cat!’ depicted a city-wide hunt for an extremely capable burglar (way more exciting than it sounds, trust me!), plus the introduction of an organised gang of thieves working for mysterious new menace The Master Planner.

Sadly, by this time of their greatest comics successes, Lee & Ditko were increasingly unable to work together on their greatest creations. Ditko’s off-beat plots and quirky art had reached an accommodation with the slickly potent superhero house-style Kirby had developed (at least as much as such a unique talent ever could). The illustration featured a marked reduction of signature line-feathering and moody backgrounds, plus a lessening of concentration on totemic villains, but – although still very much a Ditko baby – Amazing Spider-Man‘s sleek pictorial gloss warred with Lee’s scripts. These were comfortably in tune with the times if not his collaborator.

Lee’s assessment of the audience was probably the correct one, and disagreements with the artist over editorial direction were still confined to the office and not the pages themselves. However, an indication of growing tensions could be seen once Ditko began being credited as plotter of the stories…

After a period where old-fashioned crime and gangsterism predominated, science fiction themes and costumed crazies returned full force. As the world went gaga for masked mystery-men, the creators experimented with longer storylines and protracted subplots. When Ditko abruptly left, the company feared a drastic loss in quality and sales but it didn’t happen. John Romita (senior) considered himself a mere “safe pair of hands” keeping the momentum going until a better artist could be found, but instead blossomed into a major talent in his own right, and the wallcrawler continued his unstoppable rise at an accelerated pace.

Change was in the air everywhere. Included amongst the milestones for the ever-anxious Peter Parker collected here are graduating High School, starting college, meeting true love Gwen Stacy and tragic friend/foe Harry Osborn, plus the introduction of nemesis Norman Osborn. Old friends Flash Thompson and Betty Brant subsequently begin to drift out of his life…

‘If This Be My Destiny…!’ in #31 details a spate of high-tech robberies by the Master Planner culminating in a spectacular confrontation with Spider-Man. Also on show is that aforementioned college debut, first sight of Harry and Gwen, with Aunt May on the edge of death due to an innocent blood transfusion from her mildly radioactive darling Peter…

This led to indisputably Ditko’s finest and most iconic moments on the series – and perhaps of his entire career. ‘Man on a Rampage!’ shows Parker pushed to the edge of desperation as the Planner’s men make off with serums that might save May, resulting in an utterly driven, berserk wallcrawler ripping the town apart whilst trying to find them.

Trapped in an underwater fortress, pinned under tons of machinery, the hero faces his greatest failure as the clock ticks down the seconds of May’s life…

This in turn generates the most memorable visual sequence in Spidey history as the opening of ‘The Final Chapter!’ luxuriates in 5 full, glorious pages to depict the ultimate triumph of will over circumstance. Freeing himself from tons of fallen debris, Spider-Man gives his absolute all to deliver the medicine May needs, and is rewarded with a rare happy ending…

Russian exile Kraven returns in ‘The Thrill of the Hunt!’, seeking payback for past humiliations by impersonating the webspinner, after which #35 confirms that ‘The Molten Man Regrets…!’: a plot-light, inimitably action-packed combat classic wherein the gleaming golden bandit foolishly resumes his career of pinching other people’s valuables…

Amazing Spider-Man #36 offers a deliciously off-beat, quasi-comedic turn in ‘When Falls the Meteor!’, with deranged, would-be scientist Norton G. Fester calling himself The Looter to steal extraterrestrial museum exhibits…

In retrospect these brief, fight-oriented tales, coming after such an intricate, passionate epic as the Master Planner saga should have indicated something was amiss. However fans had no idea that ‘Once Upon a Time, There was a Robot…!’ – featuring a beleaguered Norman Osborn targeted by his disgraced ex-partner Mendel Strom, and some eccentrically bizarre murder-machines in #37 and the tragic tale of ‘Just a Guy Named Joe!’ – wherein a hapless sad-sack stumblebum boxer gains super-strength and a bad-temper – would be Ditko’s last arachnid adventures.

And thus an era ended…

As added enticements – and alone worth the price of this collection of much-reprinted material – is a big gallery of extras beginning with ‘…Does Whatever a Spider Can: A Lee/Ditko Amazing Spider-Man Lexicon’ and a selection of essays by Arlen Schumer, Jon B Cooke and Blake Bell including Lee’s ‘The World’s Best-Selling Swinger’. Also on view is the entire debut tale from AF #15, in original art form, taken from the Library of Congress where it now resides, fully curated and commented upon by historian and scholar Blake Bell. Also on view are unused Ditko covers, sketches, layouts and early monochrome pin-ups (33 pages in total), unretouched cover art for AS #11 & 35, and a barrage of pulse-pounding house ads, “Bullpen Bulletin” pages plus a photo-feature on the Marvel Bullpen circa 1964.

The treats go on with rare Ditko T-shirt designs, posters and ad art, plus a range of Marvel Masterworks covers with Kirby and Ditko’s original images enhanced by painters Dean White and Paul Mounts. Also included are a cover gallery for 1960s reprint vehicle Marvel Tales (#1-28 by Ditko and latterly Marie Severin) as well as Mighty Marvel Masterworks collection covers by Michael Cho and Alex Ross’ Omnibus cover art. Although other artists have inked his narratives, Ditko handled all the art on Spider-Man and these lost gems demonstrate his fluid mastery and just how much of the mesmerising magic came from his pens and brushes…

Full of energy, verve, pathos and laughs, gloriously short of post-modern angst and breast-beating, these fun classics – also available in numerous formats including eBook editions – are quintessential comic book magic constituting the very foundation of everything Marvel became. This classy compendium is an unmissable opportunity for readers of all ages to celebrate the magic and myths of the modern heroic ideal: something no serous fan can be without, and an ideal gift for any curious newcomer or nostalgic aficionado.

Happy Unbirthday Spidey and many, many more please…

© 2022 MARVEL.

For such a weighty tome, Blankets is a remarkably quick and easy read, with Thompson’s imaginative and ingenious marriage of text and images carrying one along in the way only comics can. One of the most powerful and lovely tales of first love and faith lost, this book has lost none of its charm and seductive power over the decades. If you aren’t slavishly addicted to skimpily-clad incel-fodder or punch-in-the-face comics and have held on to the slightest shreds of your innate humanity, this is that rarest of beasts – a perfect story in pictures.

For such a weighty tome, Blankets is a remarkably quick and easy read, with Thompson’s imaginative and ingenious marriage of text and images carrying one along in the way only comics can. One of the most powerful and lovely tales of first love and faith lost, this book has lost none of its charm and seductive power over the decades. If you aren’t slavishly addicted to skimpily-clad incel-fodder or punch-in-the-face comics and have held on to the slightest shreds of your innate humanity, this is that rarest of beasts – a perfect story in pictures.