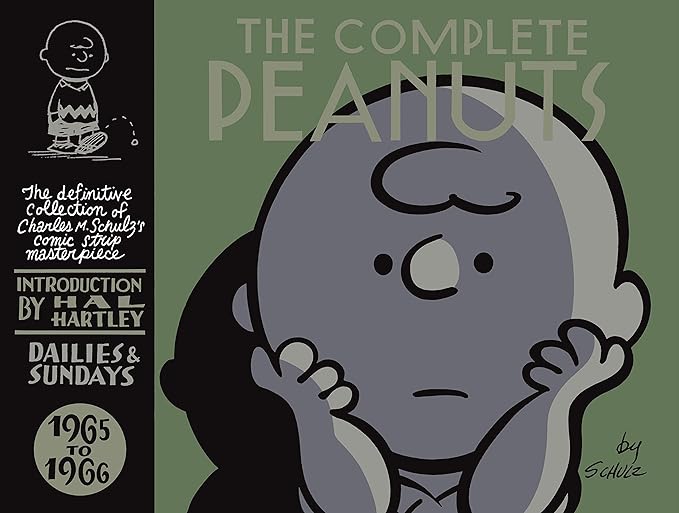

By Charles M. Schulz (Fantagraphics Books/Canongate Books UK)

ISBN: 978-1-56097-724-7 (HB) 978-1-84767-815-7 (UK HB)

Halloween’s just around the corner and so, in the spirit of beleaguered, embattled diversity, here’s a sop to those devout devotees of the sectarian offshoot awaiting with nervous anticipation the spiritual harvest of The Great Pumpkin. The rest of you can just relish the timeless cartoon mastery of a pictorial comedy genius…

Peanuts is unequivocally the most important comic strip in the history of graphic narrative. It is also the most deeply personal. Cartoonist Charles M Schulz crafted his moodily hilarious, hysterically introspective, shockingly surreal philosophical epic for half a century: 17,897 strips spanning October 2nd 1950 to February 13th 2000. He died – from complications of cancer – the day before his last strip was printed.

At its height, Peanuts ran in 2,600 newspapers, in 21 languages and75 countries. Many of those venues still run it in perpetual reprints, as they have ever since his death. During his lifetime, book collections, a merchandising mountain and television spin-offs had made the publicity-shy doodler an actual billionaire at a time when that really meant something…

None of that matters. Peanuts – a title Schulz loathed, but one the syndicate forced upon him – changed the way comics strips were received and perceived: proving cartoon comedy could have edges and nuance and meaning as well as soon-forgotten pratfalls and punchlines.

Following a thoughtful Foreword from screenwriter, director, producer, composer and independent filmmaker Hal Hartley (Trust, Henry Fool, The Unbelievable Truth, Simple Men), the timeless episodes of play, peril, psychoanalysis and personal recrimination resume. Rendered in marvellous monochrome, there are some crucial character introductions, more plot developments and the creation of even more traditions we all revere to this day. Of particular note is the end of the de facto soft revolution leaving the wonder beagle in the driving – or rather pilot’s – seat…

Mostly, though, our focus and point of contact is quintessential, inspirational loser Charlie Brown who, beside fanciful, high-maintenance mutt Snoopy, remains squarely at odds with a mercurial supporting cast, hanging out doing what at first sight seems to be Kids Stuff.

Always, gags centre on play, varying degrees of musicality, pranks, interpersonal alignments, the mounting pressures of ever-harder education, mass media through young eyes and a selection of sports in their season. leavened by agonising teasing, aroused and crushed hopes, the making of baffled observations and occasionally acting a bit too much like grown-ups.

However, with this tome, themes and tropes that define the entire series (especially in the wake of the animated TV specials) become mantra-like yet endlessly variable. One deliciously powerful constant is Brown’s inability to fly a kite, and here war with wind, gravity and landscape reaches absurdist proportions…

Mean girl Violet, prodigy Schroeder, self-taught psychoanalyst and dictator-in-waiting Lucy van Pelt, her brilliantly off-kilter little brother Linus and dirt-magnet “Pig-Pen” are fixtures honed to generate joke-routines and gag-sequences around their signature foibles, but some early characters have faded away in favour of fresh attention-attracting players joining the mob. At least the Brown boy’s existential crisis/responsibility vector/little sister Sally has grown enough to become just another trigger for relentless self-excoriation. As she grows, pesters librarians, forms opinions and propounds steadfastly authoritarian views, Charlie is relegated to being her dumber, but eternally protective big brother…

Resigned – sort of – to life as a loser in the gunsight of cruel and capricious fate, the boy Brown is helpless meat in the clutches of openly sadistic Lucy. When not sabotaging his efforts to kick a football, she monetises her spiteful verve via a 5¢ walk-in psychoanalysis booth: ensuring that whether at play, in sports, kite-flying or just brooding, the round-headed kid truly endures the character-building trials of the damned. She’s so good at it that she even expands the franchise and brings in locums…

At this time, the beagle grew into the true star of the show, with his primary quest for more and better food playing out against an increasingly baroque inner life, wild encounters with birds, skateboarding, dance marathons and skating trysts with a “girl-beagle”, philosophical ruminations, and evermore popular catchphrases. Here, the burgeoning whimsy leads to the dog’s first forays into drama (“It was a dark and stormy night…”), a hunt for the brothers and sisters he was so cruelly torn from as a pup, and the opening shots in his WWI other life, peppered with classic dogfights against the accursed Red Baron…

Snoopy is the only force capable of countering Van Pelt. Over these two years, her campaign to curb that weird beagle, cure her brother of his comfort blanket addiction and generally reorder reality to her preferences reaches astounding heights and appalling depths…

This volume opens and closes with many strips riffing on snow, and television – or the gang’s responses to it – become ever more pervasive. As aways, Lucy constantly and consistently sucks all the joy out of the white wonder stuff and the astounding variety offered by the goggle-box. Perpetually sabotaged, and facing abuse from every female in his life, Brown endures more casual grief from smug, attention-seeking Frieda, demanding constant approval for her “naturally curly hair” and championing shallow good looks over substance. Linus meanwhile is pulled in many directions: primarily between his beloved blanket and the eerie attractions of his teacher Miss Othmar…

Schulz had established way points in his year: formally celebrating certain calendar occasions – real or invented – as perennial shared events: Mothers and Fathers’ Days, Fourth of July, National Dog Week strips accompanied in their turn yearly milestones like Christmas, St. Valentine’s Day, Easter, Halloween/Great Pumpkin Day and Beethoven’s Birthday were joined this year by another American ritual as first Charlie Brown and latterly Linus are sent to summer camp. The experience heralded big changes and led to two permanent additions to the cast: camp mate and distant acquaintance Roy (debuting June 11th 1965) and eventually – on August 22nd 1966 – his pal Patricia Reichardt AKA bluff tomboy Peppermint Patty…

Endless heartbreak ensued – and escalates here – after Charlie Brown foolishly let slip his closet romantic aspirations regarding the “little red-haired girl”: a fascination outrageously exploited by others whenever he doesn’t simply sabotage himself, but the poor oaf has no idea how to respond to closer ties with his dream girl or why Patty cares…

Sports loom large and terrifying as ever, but star player Snoopy seems more interested in surfing and skateboarding than baseball and Lucy finds far more absorbing pastimes after picking up a croquet mallet and a sack for trick-or-treat candies…

Her brother, however, endures more disappointment (twice!) when again The Great Pumpkin spends Halloween night in someone’s patch. Poor Sallie also ends 1965 on a downward spiral after being diagnosed with amblyopia and forced to live with an eyepatch, just as everybody is drawn into a massive, unstoppable snowball war…

Another year and even more of the above sees lovesick sad sack Charlie sent to the Principal’s office (twice!) whilst his best bud is AWOL: continually shot down by phantom Hun The Red Baron or distracted by his growing cohort of bird buddies. Anxiety-wracked Brown even steps down from the baseball team to ease his life, but being replaced by Linus only intensifies his woes. Peppermint Patty eases some of his baseball problems but only until Linus seduces her away with impassioned proselytizing for the Great Pumpkin. As with so many others, Patty’s conversion is brief and doesn’t survive a dark night in field…

And then before you know it, there’s the traditional countdown to Christmas and another year filled with weird, wild and wonderful moments…

The Sunday page debuted on January 6th 1952: a standard half-page slot offering more measured fare than 4-panel dailies. Thwarted ambition, sporting failures, crushing frustration – much of it kite/psychoanalysis related – abound this time, alternating with Snoopy’s inner life which diversifies and intensifies into dogfights and other signature sorties as the sabbath indulgences afforded Schulz room to be his most imaginative, whimsical and provocative…

Particular moments to relish include the sharply-cornered romantic triangle involving Lucy, Schroeder & Beethoven; snow escapades, Snoopy v Lucy deathmatches; Charlie Brown’s food feud with the beagle, Lucy’s solutions to complex questions; toothbrush discipline: “tricks or treats”; doggy dreams; the growing power of television; sporting endeavours; and more…

To wrap it all up, Gary Groth celebrates and deconstructs the man and his work in ‘Charles M. Schulz: 1922 to 2000’, preceded by a copious ‘Index’ offering instant access to favourite scenes you’d like to see again…

Readily available in all formats, this volume guarantees total enjoyment: comedy gold and social glue metamorphosing into an epic of spellbinding graphic mastery that still adds joy to billions of lives, and continues to make new fans and devotees long after its maker’s passing.

The Complete Peanuts © 2007, United Features Syndicate, Ltd. 2014 Peanuts Worldwide, LLC. The Foreword is © 2007, Hal Hartley. “Charles M. Schulz: 1922 to 2000” © 2007 Gary Groth. All rights reserved.