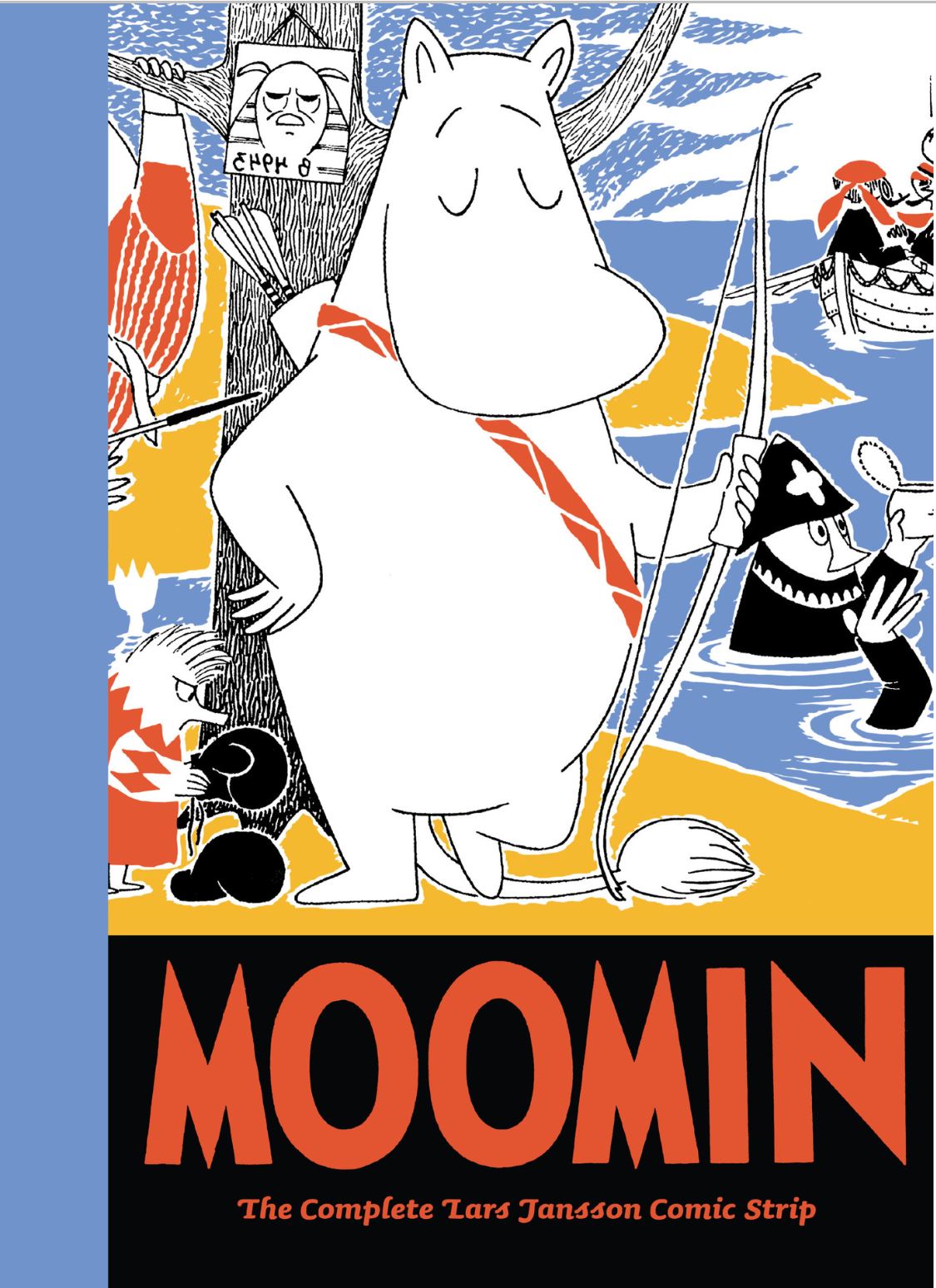

By Lars Jansson (Drawn & Quarterly)

ISBN: 978-1-77046-062-1 (HB) eISBN: 978-1-77046-554-1

Tove Jansson was one of the greatest literary innovators and narrative pioneers of the 20th century: equally adept at shaping words and images to create worlds of wonder. She was especially expressive with basic components like pen and ink, manipulating slim economical lines and patterns to realise sublime realms of fascination, whilst her dexterity made simple forms into incredibly expressive and potent symbols and, as this collection shows, so was her brother…

Tove Marika Jansson was born into an artistic, intellectual, basically bohemian Swedish family in Helsinki, Finland on August 9th 1914. Father Viktor was a sculptor and mother Signe Hammarsten-Jansson a successful illustrator, graphic designer and commercial artist. Tove’s brothers Lars – AKA “Lasse” – and Per Olov became respectively an author/cartoonist and art photographer. The family and its close intellectual, eccentric circle of friends seems to have been cast rather than born, with a witty play or challenging sitcom as the piece they were all destined to inhabit.

After extensive and intensive study (from 1930-1938 at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm, the Graphic School of the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and L’Ecole d’Adrien Holy and L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris), Tove became a successful exhibiting artist through the troubled period of the Second World War.

Brilliantly creative across many fields, she published the first fantastic Moomins adventure in 1945. Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (The Little Trolls and the Great Flood or latterly and more euphoniously The Moomins and the Great Flood) was a whimsical epic of gentle, inclusive, accepting, understanding, bohemian misfit trolls and their strange friends…

A youthful over-achiever, from 1930 to 1953 Tove worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for Swedish satirical magazine Garm: achieving some measure of notoriety with an infamous political sketch lampooning the Appeasement policies of European leaders by depicting Hitler in nappies. She was also highly in-demand for many magazines and children’s books, and had started selling comic strips as early as 1929.

Moomintroll was her signature character. Literally.

The lumpy, big-eyed, gently adventurous romantic goof began life as a spindly sigil next to her name in her political works. She called him “Snork” and claimed she had designed him in a fit of pique as a child – the ugliest thing a precocious little girl could imagine – as a response to losing an argument with her brother about Immanuel Kant.

The term “Moomin” came from her maternal uncle Einar Hammarsten who attempted to stop her pilfering food when she visited, warning her that a Moomintroll guarded the kitchen, creeping up on trespassers and breathing cold air down their necks. Snork/Moomin filled out, became timidly nicer – if a little clingy and insecure – acting as a placid therapy-tool to counteract the grimness of the post-war world.

Initially The Moomins and the Great Flood made little impact, but Jansson persisted – as much for her own edification as any other reason – and in 1946 Kometjakten (Comet in Moominland) was published. Many commentators regard the terrifying tale a skilfully compelling allegory of Nuclear Armageddon. You should read it now… while you still can…

When it and third illustrated novel Trollkarlens hatt (1948, Finn Family Moomintroll or occasionally The Happy Moomins) were translated into English in 1952, their instant success prompted British publishing giant Associated Press to commission a newspaper strip about her seductively sweet and sensibly surreal creations.

Jansson had no misgivings or prejudices regarding strip cartoons and had already adapted Comet in Moominland for Swedish/Finnish paper Ny Tid. Mumintrollet och jordens undergäng – Moomintrolls and the End of the World – was a popular feature, so she readily accepted the chance to extend her eclectic family across the world. In 1953, The London Evening News began the first of 21 Moomin strip serials to captivate readers of all ages.

Jansson’s involvement in the cartoon feature ended in 1959, a casualty of its own success and a punishing publication schedule. So great was the strain that towards the end she recruited brother Lars to help. He then took over, continuing the strip until 1975. His tenure as sole creator continues here…

Liberated from the strip’s pressures, Tove returned to painting, writing and other creative pursuits: making plays, murals, public art, stage designs, costumes for dramas and ballets, a Moomin opera and 9 more Moomin-related picture-books and novels, as well as 13 books and short-story collections strictly for grown-ups.

Tove Jansson died on June 27th 2001. Her awards are too numerous to mention, but just consider: how many modern artists get their faces on the national currency?

Lars Fredrik Jansson (October 8th 1926 – July 31st 2000) was just as amazing as his sister. Born into that astounding clan twelve years after Tove, at 16 he started writing – and selling – novels (nine in total). He also taught himself English because there weren’t enough Swedish-language translations of books available for his voracious reading appetite.

In 1956, he began co-scripting the Moomin newspaper strip at his sister’s request: injecting his own brand of witty whimsicality to ‘Moomin Goes Wild West’. He had been Tove’s translator from the start, seamlessly converting her Swedish text into English. When her contract with The London Evening News expired in 1959, Lars Jansson officially took over the feature, having spent the interim period learning to draw and perfectly mimic his sister’s cartooning style. He had done so in secret, with the assistance and tutelage of their mother Signe. From 1961 to the strip’s end in 1974, he was sole steersman of the newspaper iteration of trollish tails.

Lasse was a man of many parts: other careers including writer, translator, aerial photographer and professional gold miner. He was the basis and model for the cast’s cool kid Snufkin…

Lars’ Moomins was subtly sharper than his sister’s version and he was far more in tune with the quirky British sense of humour, but his whimsy and wry sense of wonder was every bit as compelling. In 1990, long after the original series, he began a new career, working with Dennis Livson (designer of Finland’s acclaimed theme park Moomin World) as producers of Japanese anime series The Moomins and – in 1993 with daughter Sophia – on new Moomin strips…

Moomintrolls are easy-going free spirits: natural bohemians untroubled by hidebound domestic mores and most societal pressures. Moominmama is warm, kindly tolerant and capable but perhaps overly concerned with propriety and appearances, whilst devoted spouse Moominpappa spends most of his time trying to rekindle his adventurous youth or dreaming of fantastic exploits.

Their son Moomin is a meek, dreamy boy with confusing ambitions. He adores their permanent houseguest the Snorkmaiden – although that impressionable, flighty gamin much prefers to play things slowly whilst hoping for somebody potentially better to come along…

The seventh oversized (310 x 221 mm) monochrome hardback compilation gathers serial strip sagas #26-29, and opens with Lars firmly in charge and puckishly re-exploring human frailties and foibles via a sophisticate poke at the shifting political climate…

Craftily casting cats among pigeons, 26th escapade ‘Moomin the Colonist’ finds armchair adventurer Moominpappa resenting the advent of the annual hibernation and rashly listening to his bookish boy, who has been reading about colonisation…

Soon he has packed up the family and a few close friends and set out to conquer fresh fields and pastures new. With Mymble and Little My, Mrs Fillyjonk, her daughters and a cow in tow, the eager expansionists head off across the frozen land and don’t stop until they reach a tropical desert island where they start setting up a new civilisation combining the best of the old world with lots of fresh ideas on how society should be run…

Sadly, their neighbours from back home have sneakily copied the Moomin movement and before long the new continent is embroiled in a passive-aggressive, slyly competitive struggle for control, with scurrilous reprobate Stinky and his pals playing the bad guys behind the Palm Tree Curtain…

Following the mutual collapse of colonialism, outrageous satire gives way to wicked sarcasm as ‘Moomin and the Scouts’ recounts how energetic Mr Brisk’s passion for the outdoor life, badges and bossing children envelopes the instinctively sedentary Moomins and unleashes all kinds of disruptive chaos. With scouts running wild amongst the trees it just seems easier to join them rather than seek to beat them and let nature disrupt the movement from within…especially after Moomin starts hanging around with Miss Brisk’s Girl Guides and the generally dismissive Snorkmaiden feels oddly conflicted…

The perils of property and stain of status upsets the orderly life of the clan when Moominpappa unexpectedly comes into a major inheritance in ‘Moomin and the Farm’. Grievously afflicted by a terrible case of noblesse oblige, the family uproot themselves and retire to stately Gobble Manor to perpetuate the line of landed gentry on a modern working arable and pastoral estate.

Adapting to wealth and property is one thing and even accommodating the legion of ancestral ghosts is but another strand of Duty, but the effort of taking on and even perpetuating centuries of unearned privilege proves far too weighty a burden for all concerned… before the increasingly untenable situation typically corrects itself…

Back in their beloved house and rearranging furniture, a dropped chest disgorges an ancient map and triggers another wild dreamers’ quest in ‘Moomin and the Gold-fields’…

Unable to refuse adventure when it’s dangled in front of their exuberant noses, father and son are soon trekking the wilds and digging random holes thanks to the supremely unclear chart, and before long the entire valley is afflicted with gold rush fever.

With law, common decency and even good manners abandoned to greed as the sedate dell becomes a boisterous and sordid boom town, all Moominmama can do is maintain her dignity and wait for the madness to pass…

This deceptively barbed and edgy compilation closes with ‘Lars Jansson: Roll Up Your Sleeves and Get to Work’ by family biographer Juhani Tolvanen, extolling his many worthy attributes and more besides…

These are truly magical tales for the young, laced with the devastating observation and razor-sharp mature wit which enhances and elevates only the greatest kids’ stories into classics of literature. These volumes – both Tove and Lars’ – comprise an international treasure trove no fan of the medium – or carbon-based lifeform with even a hint of heart and soul – can afford to be without.

© 2012 Solo/Bulls except “Lars Jansson: Roll Up Your Sleeves and Get to Work” © 2011, 2012 Juhani Tolvanen. All rights reserved.