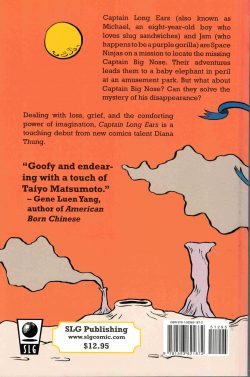

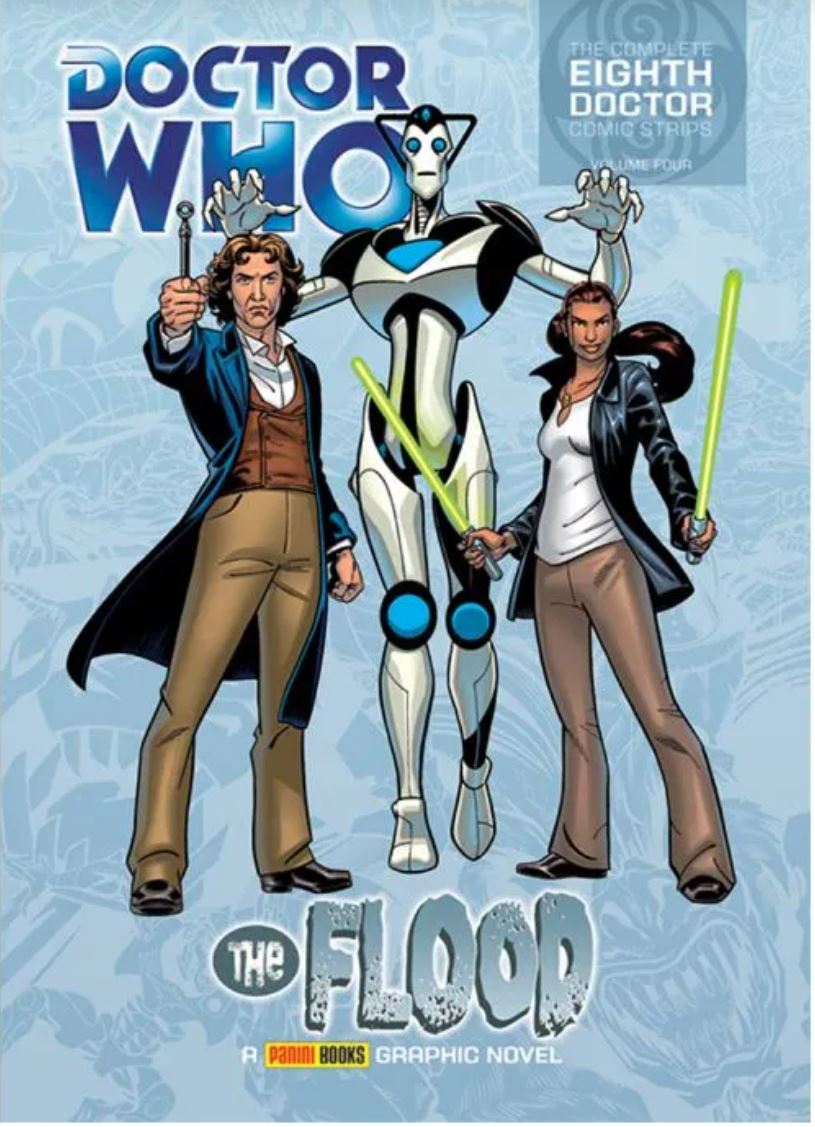

By Scott Gray, Gareth Roberts, Roger Langridge, David A. Roach, Mike Collins, Robin Smith, Adrian Salmon, Anthony Williams, Martin Geraghty, Faz Choudhury, Daryl Joyce, John Ross & various (Panini Books)

ISBN 978-1-905239-65-8 (TPB)

This year is the 60th Anniversary of Doctor Who so there is/has been/will be a bunch of Timey-Wimey stuff on-going as we periodically celebrate a unique TV and comics institution…

The British love comic strips and they love celebrity and they love “characters.” The history of our homegrown graphic narratives includes a disproportionate number of radio comedians, Variety stars and television actors: such disparate legends as Charlie Chaplin, Flanagan & Allen, Arthur Askey, Winifred Atwell, Max Bygraves, Jimmy Edwards, Charlie Drake and so many more I’ve long forgotten and you’ve likely never heard of.

As much adored and adapted were actual shows and properties like Whacko!, ITMA, Our Gang, Old Mother Riley, Supercar, Thunderbirds, Pinky and Perky, The Clangers and literally hundreds of others. If folk watched or listened, an enterprising publisher would make printed spectacles of them. Hugely popular anthology comics including Radio Fun, Film Fun, TV Fun, Look-In, TV Tornado, TV Comic and Countdown readily translated our light entertainment favourites into pictorial joy every week, and it was a pretty poor star or show that couldn’t parley the day job into a licensed strip property…

Doctor Who premiered on black-&-white televisions across Britain on November 23rd 1963 with the first episode of ‘An Unearthly Child’. In 1964, a decades-long association with TV Comic began: issue #674 heralding the initial instalment of ‘The Klepton Parasites’.

On 11th October 1979 (although adhering to the US off-sale cover-dating system so it says 17th), Marvel’s UK subsidiary launched Doctor Who Weekly. Turning into a monthly magazine in September 1980 (#44) it’s been with us – under various names and iterations – ever since. All of which only goes to prove the Time Lord is a comic star not to trifled with.

Panini’s UK division ensured the immortality of the comics feature by collecting all strips of every Regeneration of the Time Lord in a uniform series of over-sized graphic albums.

This is actually the forth – and final – collection of their strips featuring the Eighth (Paul McGann) Doctor. Whether that statement made any sense to you largely depends on whether you are an old fan, a new convert or even a complete beginner.

None of which is relevant or pertinent if all you want is a darn good read. The creators involved have managed the ultimate ‘Ask’ of any comics creator – producing engaging, thrilling, fun strips that can be equally enjoyed by the merest beginner and the most slavishly dedicated fan.

Writer Scott Gray provides a smart script for Roger Langridge & David A. Roach’s potent art with ‘Where Nobody Knows Your Name’ as the errant Time-Lord fetches up at a bar and meets some old friends, before Gareth Roberts spoofs the entire British Football comics industry in ‘The Nightmare Game’. Pictorial fun and thrills in equal measure are provided by Mike Collins & Robin Smith on this nostalgia-drenched 3-parter.

Gray writes everything else in the book, starting with a short adventure in ancient Egypt. ‘The Power of Thoueris!’ is stylishly illustrated by Adrian Salmon, and is followed by an extended Victorian romp illustrated by Anthony Williams & Roach concerning ‘The Curious Tale of Spring-Heeled Jack’.

‘The Land of Happy Endings’ is a touching and engagingly heartfelt tribute to the days of the TV hero’s earliest strip outings. Writer Gray, penciller Martin Geraghty, inkers Roach and Faz Choudhury with painter/colourists Daryl Joyce & Salmon all tip their collective hats to Neville Main (illustrator of the first graphic adventures of the Doctor beginning in 1964 in TV Comic) in a charming retro-romp, which clears the palate for a horror-fest set in 1875 Dakota.

‘Bad Blood’ has werewolves, shamanism, ghost-towns, cowboys, George Armstrong Custer and Sitting Bull as well as the requisite aliens and evil technology rioting through its five chapters, all ably illustrated by Geraghty, Roach & Salmon in an enthralling thriller leaving the Time Lord with brand new Companion Destrii.

Drawn by John Ross and coloured by Salmon, ‘Sins of the Fathers’ deals with the aftermath of that conflict. The severely wounded Destrii must be rushed to a deep-space hospital just in time for it to be attacked by Zero-G terrorists. Both this 3-parter and follow-up epic ‘The Flood’ have extended endings that had never been published before.

The latter is the real gem of this book; a huge, 8-chapter saga originally intended to conclude the McGann Doctor adventures and bridge the gap to the new TV series with incoming Christopher Eccleston as the new resurgent Time Lord. Just how that all worked out makes for fascinating reading in the wonderful text section at the back, but Gray, Geraghty, Roach, Salmon & Langridge go out with a bang as Cybermen invade Camden on their way to world domination. This is an absolute joy, full of action, suspense, humour and the kind of cameos all fan-boys die for.

We’ve all got our little joys and hidden passions. Sometimes they overlap and magic is made. This is a great set of strips, about a meta-literally immortal and timeless TV hero. If you’re a fan of only one, this book might make you an addict to both.

All Doctor Who material © BBCtv. Doctor Who, the Tardis and all logos are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. Death’s Head and The Sleeze Brothers © Marvel. Published 2007. All rights reserved.