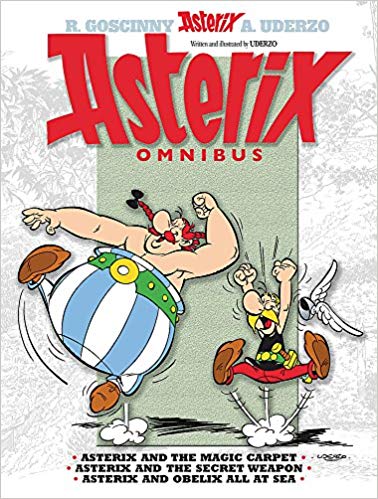

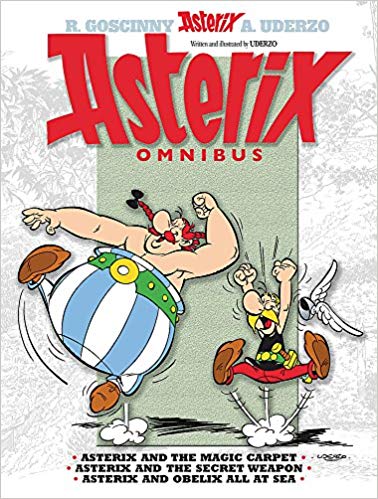

By Uderzo, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Orion Childrens’ Books and others)

ISBNs: 978-1-40910-134-5 (HB Album) 978-1-44400-425-0 (PB)

Win’s Christmas Gift Recommendation: Celebrating the Season with Historical Hysterics… 10/10

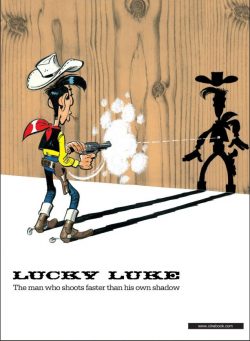

Alberto Aleandro Uderzo was born on April 25th 1927 in Fismes, on the Marne, a son of Italian immigrants. Showing great artistic flair as a child reading Mickey Mouse in Le Pétit Parisien, he dreamed of becoming an aircraft mechanic one day.

He became a French citizen at age seven and found employment at 13, apprenticed to the Paris Publishing Society, where he learned design, typography, calligraphy and photo retouching.

When WWII broke out, Albert spent time with farming relatives in Brittany and joined his father’s furniture-making business. Brittany beguiled and fascinated Uderzo: when a location for Asterix’s idyllic village was being mooted, the region was the only choice.

During the post-war rebuilding of France, Uderzo returned to Paris and became a successful artist in the country’s revitalised and burgeoning comics industry. His first published work – a pastiche of Aesop’s Fables – appeared in Junior, and in 1945 he was introduced to industry giant Edmond-François Calvo (whose own comics masterpiece The Beast is Dead is long overdue for a new edition and, if you follow current events, sorely needed as a warning shot…).

Indefatigable Uderzo’s subsequent creations included indomitable eccentric Clopinard, Belloy, l’Invulnérable, Prince Rollin and Arys Buck. He illustrated Em-Ré-Vil’s novel Flamberge, worked in animation, as a journalist and illustrator for France Dimanche, and created vertical comic strip Le Crime ne Paie pas for France-Soir. In 1950, he illustrated a few episodes of the franchised European version of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Jr. for Bravo!

An inveterate traveller, the prodigy met Rene Goscinny in 1951. Soon fast friends, they decided to work together at the new Paris office of Belgian publishing giant World Press. Their first collaboration was in November of that year; a feature piece on savoir vivre (how to live right, or perhaps gracious living) for women’s weekly Bonnes Soirée, after which an avalanche of splendid strips and serials poured forth.

Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior were created for La Libre Junior before they devised a western with a native hero who eventually evolved into the delightfully infamous Oumpah-Pah. In 1955, with the formation of Édifrance/Édipresse, Uderzo drew Bill Blanchart for La Libre Junior, replaced Christian Godard on Benjamin et Benjamine, and in 1957 added Charlier’s Clairette to his bulging portfolio.

The following year he made his debut in Le Journal de Tintin, as Oumpah-Pah finally found a home and rapturous audience. In his quieter moments Uderzo also drew Poussin et Poussif, La Famille Moutonet and La Famille Cokalane.

When Pilote launched in 1959, Uderzo was a major creative force for the new magazine, collaborating with Charlier on Tanguy et Laverdure and launching – with Goscinny – a little something called Astérix le gaulois…

Despite Asterix being a massive hit from the start, Uderzo continued working on Les Aventures de Tanguy et Laverdure, but once the first Roman romp was compiled and collected as hit album Ast̩rix le gaulois in 1961, it became clear that the series would demand most of his time Рespecially as the incredible Goscinny seemed to never require rest or run out of ideas.

By 1967 the strip occupied all Uderzo’s time and attention, so in 1974 the partners formed Idéfix Studios to fully exploit their inimitable creation. When Goscinny passed away three years later, Uderzo had to be convinced to continue the adventures as writer and artist, producing a further ten volumes until 2010 when he retired.

After nearly 15 years as a weekly comic strip subsequently collected into albums, in 1974 the 21st tale (Asterix and Caesar’s Gift) was the first to be published as a complete original book before being serialised. Thereafter, each new release was a long-anticipated, eagerly-awaited treat for the strip’s millions of fans…

According to UNESCO’s Index Translationum, Uderzo is the 10th most-often translated French-language author in the world and the third most-translated French language comics author – right after his old mate René Goscinny and the grand master Hergé.

Global sales will soon top 380 million copies of the 38 canonical Asterix books, making his joint creators – and their successors Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad – France’s best-selling international authors.

One of the most popular comics features on Earth, the collected chronicles of Asterix the Gaul have been translated into more than 100 languages since his debut, with a wealth of animated and live-action movies, TV series, assorted games, toys, merchandise and even a theme park outside Paris (Parc Astérix, naturellement)…

So what’s it all about?

Like all the best stories the premise works on more than one level: read it as an action-packed comedic saga of sneaky and bullying baddies coming a cropper if you want or as a punfully sly and witty satire for older, wiser heads. We Brits are further blessed by the brilliantly light touch of master translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who played no small part in making the indomitable little Gaul so very palatable to English tongues.

More than half of the canon is set on Uderzo’s beloved Brittany coast, where – circa 50 B.C. – a small village of cantankerous, proudly defiant warriors and their families resist every effort of the mighty Roman Empire to complete the conquest of Gaul. The land has been divided by the conquerors into compliant provinces Celtica, Aquitania and Amorica, but the very tip of the last cited just refuses to be pacified…

The remaining epics occur in various locales throughout the Ancient World, with the Garrulous Gallic Gentlemen visiting every fantastic land and corner of the myriad civilisations that proliferated in that fabled era…

When the heroes are playing at home, the Romans, unable to defeat the last bastion of Gallic insouciance, futilely resort to a policy of absolute containment. Thus, the little seaside hamlet is permanently hemmed in by the heavily fortified garrisons of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.

The Gauls couldn’t care less: daily defying the world’s greatest military machine simply by going about their everyday affairs, protected by the magic potion of resident druid Getafix and the shrewd wits of the diminutive dynamo and his simplistic, supercharged best friend Obelix…

Firmly established as a global brand and premium French export by the mid-1960s, Asterix continued to grow in quality as Goscinny & Uderzo toiled ever onward, crafting further fabulous sagas; building a stunning legacy of graphic excellence and storytelling gold. Moreover, following the civil unrest and nigh-revolution in French society following the Paris riots of 1968, the tales took on an increasingly acerbic tang of trenchant satire and pithy socio-political commentary…

By the time of the first tale in this omnibus edition was released Goscinny had been gone for a decade and Uderzo was slowly but surely finding his own authorial voice…

Asterix and the Magic Carpet (originally and rather ponderously entitled Astérix chez Rahà zade ou Le compte des mille et une heures – which translates as Asterix meets Orinjade or the 1001 Hours Countdown) was released in 1987 and once again saw Asterix and Obelix undertake a long voyage into the unknown: one packed with exotic climes, odd people and bold adventure, all deliciously underpinned by topical lampooning and timeless swingeing satire.

Before the Arabian adventure begins, a delightful in-character portrait of Goscinny and Uderzo as their greatest creations Asterix and Obelix whets the appetite for the fun to come, after which the 28th saga starts with a friendly feast, abruptly ruined twice over by the musical efforts of raucous Bard Cacofonix.

Firstly, there’s the plain fact that he is singing at all, but the real problem is that his newly discovered vocal style summons up storms and creates violent downpours.

The thunderous deluge delivers a surprised visitor to the village. Watziznehm the Fakir was passing by far above on his flying carpet when the tempest tossed him to earth. It’s a painful but happy accident since the Indian wise man is on a mission to find some miraculous Gauls and a certified rainmaker…

Soon Asterix, Obelix and canine wonder Dogmatix are heading Due East to save beautiful princess Orinjade from the machinations of Guru Hoodunnit, who wants to sacrifice her to end a terrible drought and consequently seize the reins of power from her father Rajah Watzit. When the flying wizard left home, it was with a countdown of 1001 hours to doomsday…

Our heroes are only accompanying the real star of the Fakir’s quest: with a deadline looming to execute the princess, Watziznehm needs to get Cacofonix there in time to sing up a storm – or rather a monsoon…

Travel aboard a flying carpet is swift and comfortable but ever-hungry Obelix is continually holding up proceedings with many pit-stops to refuel his cavernous stomach, whilst the Bard’s practising frequently leads to stormy weather and unnecessary diversions…

After the usual dalliance with pirates, a bird’s eye tour of Rome and a brief voyage on a Greek trading ship, our tourists soar over Athens and get shot at above Tyre before a natural storm sets the carpet alight and they crash-land in Persia.

Despite being in the land of carpets, the travellers are unable to secure a replacement until a band of Scythian raiders attack the village. Once Asterix and Obelix negotiate a trade deal, the embattled villagers take charge of hundreds of pummelled plunderers in return for a freshly unbeatable new rug…

As the heroes plunge ever eastward, in the Valley of the Ganges Hoodunnit and his creepy mystic crony Owzat gloat at their impending takeover, even as poor Orinjade’s stout defiance begins to weaken.

When the Gauls and their Fakir chauffeur arrive with only a day to spare, it all seems over for the ghastly guru, but as the Bard begins his song, Cacofonix discovers that the arduous journey has given him laryngitis.

For the first time ever, somebody wants him to sing and he has lost his voice…

With time running out, the Rajah’s doctors’ diagnosis seems crazy: immersion in various unwholesome by-products of sacred elephants. Rather than settle for half-measures the Gauls decide to take Cacofonix to the jungle abode of Howdoo the Elephant Trainer and bury him in the curative well away from civilised senses…

This only gives the villains the opportunity they have been hoping for. When Watziznehm and the Gauls go to collect the Bard in the morning, Owzat engages the Fakir in a magical duel. Leaving them to their tricks Asterix and Obelix press on and find that the storm-singer has been kidnapped…

Happily, dashing Dogmatix is on hand to track down the Bard, an especially easy task as he now smells like he sings…

Hoodunnit is mirthfully preparing the stage for Orinjade’s sacrifice when, after the usual Gallic fisticuffs from our heroes, Cacofonix makes his Asian debut and sets everything – including the skies – to rights in the very nick of time…

Stuffed with light-hearted action, good-natured joshing, raucous, bombastic, bellicose hi-jinks and a torrent of punishing puns to astound and bemuse youngsters of all ages, this tale is full of Eastern Promise, a sublime slice of whimsy and all you need to make any holiday excursion or comfy staycation unforgettable.

The 29th volume Asterix and the Secret Weapon (originally Astérix: La Rose et le Glaive) was released in 1991 and Uderzo’s fifth as solo creator. It begins in the boisterous, far from idyllic little hamlet with a multi-generational battle of the sexes in full swing…

The perpetual jockeying for position between males and females comes to a head when Chief’s wife Impedimenta and the village matrons fire Cacofonix from his role as teacher of their children and bring in a new educator more to their liking.

Bard Bravura is a woman – and someone who knows how to get things done properly. With the village men reluctant to get involved, Cacofonix has no choice but to resign in high dudgeon and go live in the forest…

The situation worsens when the massed mothers demand a party to welcome their new tutor and Chief Vitalstatistix is bullied into arranging it. At the feast, Bravura sings and is discovered to be just slightly less awful than Cacofonix ever was. At least her bellowing doesn’t result in instant thunderstorms…

Meanwhile in Rome, Julius Caesar is listening to another bright spark with an idea to defeat and destroy the Gallic Gadflies who won’t admit they are part of his empire. Wily Manlius Claphamomnibus is convinced he has discovered a fatal chink in the rebels’ indomitable armour…

Bravura is rapidly becoming unwelcome to at least half the village: enflaming the women with her talk of “masculine tyrannyâ€, and aggravating the men by singing every morning before the sun comes up. She even manages to offend easygoing Obelix by refusing to let him bring Dogmatix to the kindergarten class his owner attends every day…

Most shocking of all, the Bard has convinced the women to wear trousers rather than skirts, and Impedimenta has taken to being carried around on a shield just like a proper – Male – Chief…

With the situation rapidly becoming intolerable, outraged Vitalstatistix orders his top troubleshooter to sort it out, but Bravura won’t listen to the diminutive warrior. She thinks Asterix is an adorable little man and bamboozles him into giving her his hut.

… And at sea a band of phenomenally unlucky pirates attack a Roman ship filled with Claphamomnibus’ secret weapons and quickly wish it had been the Gauls who usually thrash and sink them, instead of these monsters sending them to the bottom of the sea…

Relations have completely broken down in the village. The new Bard’s suggestion that Impedimenta should be chief has resulted in a massive spat and Vitalstatistix has repaired to the forest for the foreseeable future. It’s not long before every man in town joins him…

In an effort to calm the seething waters, Druid Getafix organises a referendum to decide who should rule, but whilst all the women naturally vote for Impedimenta, no men except Asterix and Obelix dare to vote for Vitalstatistix. After all, they don’t have wives…

When the little warrior confronts Bravura, she again belittles him: even suggesting that if they get together, they can rule the village jointly. Incensed beyond endurance, the furious hero slaps her when she kisses him and immediately crumbles in shock and horror.

He has committed the unpardonable sin. The Gaulish Code utterly forbids warriors to harm women or maltreat guests and in his honest outrage has betrayed his most sacred principles…

He’s still in shock when Getafix defends him at a trial where Bravura even angers the wise old sage to the point that he also storms off to join Cacofonix and Vitalstatistix…

Before day’s end the entire male contingent – overcome by a wave of masculine solidarity and “Sod This-ery†– is living a life of carefree joy under the stars and Impedimenta is rightly concerned with how the village can be defended without the Druid’s potions.

Bravura has an answer to that too: an infallible peace plan to present to the besieging Romans…

Meanwhile on the dock at Aquarium, the Secret Weapons are disembarking to the amusement and – quite quickly – sheer terror and consternation of the weary garrison. From the safety of some bushes, Asterix and Obelix watch in astonishment as an army of ferocious women – a female Legion of lethal warriors – takes over the running of the fort and prepares for total war…

Extremely worried, the spies quickly report back to the men in the trees. The situation is truly dire for no honourable Gaul could possibly fight a woman. Despite the ongoing domestic situation, Vitalstatistix decides the women of the village must be warned and despatches the horrified Asterix and still-bewildered Obelix to carry the message.

Worried and nervous at their potential reception, the unlikely lads wander into a rather embarrassing fashion show and are greeted with a wave of questions from the women who are missing their men more that they realised…

Bravura arrogantly refuses the offer to provide the women with their own magic potion, confident in her peace plan, but when she meets with Claphamomnibus she is beaten, abused and humiliated by the cocky Roman. She surprisingly finds a sympathetic ear and keen collaborator in Asterix, who has a scheme to take appropriate vengeance and send the notionally irresistible female furies packing…

It will, of course, mean the men and women of the village working closely together…

Although quite heavy-handed by today’s standards, this is at its core a superb lampooning of the endlessly entertaining “Battle of the Sexesâ€: combining swingeing satire, broad slapstick and surreal comedy in a delicious confection of sexual frisson and eternally evergreen “My Wife…†jokes.

Bravura is one of Uderzo’s most enigmatic caricatures, bearing resemblances to a number of high profile female public figures of the time, including then-French Prime Minister Edith Cresson, Belgian tele-journalist Christine Ockrent and German operatic star Diana Damrau, but the grievances of both male and female combatants are as unchanging and perennial as the characters here who enact and – for a short time at least – embody them…

Uderzo’s sixth solo session was Asterix and Obelix All at Sea (released in 1996 as La Galère d’Obélix) and the 30th volume of the ever-unfolding saga.

It opens in the cruel and callous capital of civilisation wherein the Master of the World is having a bit of a bad day. Not as bad, however, as his Grand Admiral Crustacius, who has just allowed a bunch of galley slaves to mutiny and steal Julius Caesar’s personal galley…

As the severely tongue-lashed mariner and his browbeaten aide Vice-Admiral Nautilus scurry away to pursue the fugitives, aboard the magnificent vessel magnificent Greek rebel Spartakis – bearing a striking resemblance to the magnificent Kirk Douglas in all his glory – debates with his recently-liberated comrades from many nations on where in the Rome-ruled world they can go to remain free…

A British oarsman then suggests a certain Gaulish village on the coast of Armorica which the empire has never conquered…

Meanwhile in the faraway subject of the rebels’ discussions, Asterix and Obelix are in an argumentative mood too, but their clash is put aside when word comes that the entire complement of all four encircling garrisons are massing on the far side of the forest…

Always eager for a little martial recreation, the villagers dose up on Getafix the Druid’s strength-boosting magic potion. Once again, Obelix is frustrated in his attempt to get a share of the tantalising elixir and stumbles off in high dudgeon. The generally genial giant had fallen into a vat of potion as a baby and grown up a permanently superhuman, eternally hungry hulk who hates being told no and doesn’t believe more of the mouth-watering miracle mixture might harm him…

The Romans are utterly unaware of the danger insouciantly sauntering towards them, engaged as they are in military drills to celebrate the imminent arrival of Admiral Crustacius. Thoroughly thrashing the amassed legions, the victorious Gauls wonder why Roman-bashing addict Obelix is absent and Getafix, dreading the worst, dashes back to discover his greatest fears realised.

The intransigent idiot has foolishly imbibed deeply from the potion and been turned to stone…

Nothing the Druid can conceive seems able to cure the calcified colossus and it’s during this time of trouble that Spartakis and his freed slaves arrive, requesting sanctuary. As the welcoming villagers carry the huge ornate galley into the village, the Obelix ordeal takes a strange turn as his stony spell wears off and the former fighting fool returns to flesh and blood – albeit as the puny helpless little boy he was before ever falling into the potion pot. The little wimp can’t even eat roast boar anymore…

The puny pipsqueak is the darling of the town but cannot abide his weak ineffectual status. The situation becomes truly intolerable after the boy is captured by Crustacius and shipped off to Rome. After suitably castigating the soldiery, Asterix, Getafix and faithful mutt Dogmatix give chase in Caesar’s ship, crewed by Spartakis and his valiant band of brothers.

Powered by potion, the pursuers easily overtake the Romans, who have been hampered by the obnoxious antics of Obelix and the predations of the perennially, phenomenally unlucky pirates to whom – after a period of traditional chastisement – Asterix gives Caesar’s stolen galley.

Crucially, however, in his haste the little warrior leaves behind a barrel of potion when his comrades and little Obelix all transfer to a new, less conspicuous vessel.

As the Gauls sail off in the pirate’s ship, Getafix has an inspired idea and suggests to Spartakis that they make for the last remnant of Atlantis, explaining that the idyllic Canary Islands survived the inundation of the magic continent and the people living there now are reclusive beings of great power and knowledge who might be able to restore Obelix to his natural state…

When they arrive in that beautiful land of miracles, they are greeted by aged Absolutlifabulos and hordes of beautiful, happy children riding dolphins, centaurs, swans and winged cattle. The jolly dotard explains that the Atlanteans reverted themselves to carefree immortal childhood, but their powers cannot do anything to cure Obelix. As the downhearted Gauls make their way home, Spartakis and his men opt to stay and become forever kids too…

Meanwhile on Caesar’s galley, Crustacius has discovered Getafix’s stashed potion and powered up, dreaming of ousting his foul-tempered boss and making himself Emperor, even as leagues away, a Roman boarding party invades the pirate galley and menaces the powerless Gauls.

With Asterix about to be killed, little Obelix goes berserk and the emotional overload restores him to his corpulent, hyper-charged older self, much to the distress of the terrified soldiers…

By the time Crustacius reaches Rome, he has made the same mistake Obelix did and his rapid overdosing on potion only provides Julius Caesar with another statue for the Circus Maximus…

In Gaul however, Obelix – with a lot of frustration to work through – debarks at recently repaired Aquarium for a spot of cathartic violence before he accompanies his faithful chums back to the village for a celebratory feast…

This rollicking fantasy and paean to family and true friendship cemented Uderzo’s reputation as a storyteller whilst his stunning illustrative ability affords glimpses of sheer magic to lovers of cartoon art. Asterix and Obelix All at Sea proves that the potion-powered paragons of Gallic Pride will never lose their potent punch. If you still haven’t experienced this sublime slice of French polish and graphic élan, it’s never too late…

© 1980-1996 Goscinny/Uderzo. Revised English translation © 2002-2003 Hachette. All rights reserved.