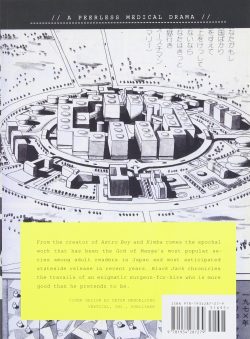

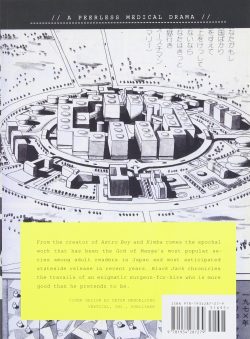

By Osamu Tezuka, translated by Camelia Nieh (Vertical)

ISBN: 978-1934287-27-9 (TankÅbon PB)

There aren’t many Names in comics. Lots of creators; multi-disciplined or single focussed, who have contributed to the body of the art form, but we don’t have many Global Presences whose contribution have affected generations of readers and aspirants all over the World, like a Mozart or Michelangelo or Shakespeare. There’s just Hergé and Jack Kirby and Osamu Tezuka.

Tezuka was born in Qsaka Prefecture on 3rd November 1928, and as a child suffered a severe illness that made his arms swell. The doctor who cured him inspired him to study medicine, and although Osamu began his professional drawing career while at university, he persevered with his studies and qualified as a doctor too. As he faced a career crossroads, his mother advised him to do the thing that made him happiest. He never practiced as a healer but the world was gifted with such classic cartoon masterpieces as Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro-boy), Kimba the White Lion, Buddha, Adolf and literally hundreds of other graphic narratives. Along the way Tezuka incidentally pioneered, if not created, the Japanese anime industry…

Able to speak to the hearts and minds of children and adults equally, Tezuka’s work ranges from the charming to the disturbing and even terrifying. In 1973 he turned his storyteller’s heart to the realm of medicine and created Burakku Jakku, a lone wolf surgeon living outside society’s boundaries and rules: a scarred and seemingly heartless mercenary working miracles for the right price but also a deeply human wounded soul who makes surgical magic from behind icy walls of cool indifference and casual hostility – think Silas Marner before the moppet turns up or Ebenezer Scrooge before bedtime; except Black Jack never, ever gets soft and cuddly.

These translated, collected adventures – available paperback and digital formats – begin with the frankly startling ‘Is There a Doctor?’, wherein the joyriding son of the richest man in the world is critically injured. The boy’s ruthless father forces Black Jack to perform a full body transplant on an unwilling victim… but the super-surgeon still manages to turn the tables on the vile plutocrat…

Each story is self-contained over about 20 pages, and the second – ‘The First Storm of Spring’ – tells the eerie, poignant tale of a young girl whose corneal transplant has gone strangely awry. Can the handsome boy she keeps seeing possibly be the ghostly original owner of the eye, and if so, what was he truly like?

With ‘Teratoid Cystoma’ the series solidly enters into fantasy territory whilst ramping up the medical authenticity. Tezuka chose to draw in a highly stylised, “Big-foot†manner (he was the acknowledged inventor of the Manga Big-Eyes artistic device) but with increasing dependence on surgical and anatomical veracity, his innate ability to render anatomy and organs realistically truly came to the fore.

A teratonous cystoma occurs when twins are conceived but one of the embryos fails to cohere. Undifferentiated portions of one twin, a limb or organ grows within and nourished by the other. As the surviving twin matures, the enclosed “spare parts†start to distend the body, appearing like a cyst or growth.

For the sake of narrative – and possibly to just plain freak you out – in this story a famous personage wishing total discretion requires the Ronin Doctor to remove a huge growth from her. Many Japanese have a frankly unhealthy prejudice against physical imperfection – for more search “the Hibakusha†– and this case is a much about stigma and position as wellbeing…

The mystery patient’s problem is exacerbated because whenever other surgeons have tried to operate, they have been debilitated by a telepathic assault from the growth. Overcoming incredible resistance, Black Jack succeeds, removing a fully-formed brain and nervous system. Ignoring the disgust of the patient and doctors, he then builds an artificial body for the stunted, sentient remnants; and calls her Pinoko.

‘The Face Sore’ combines Japanese legends of the Jinmenso (intelligent, garrulous tumours) with cases of disfiguring carbuncles and rashes to produce a very scary modern horror story – and by modern, I mean lacking a happy ending…

Pinoko, looking like a little girl (whether she’s a year old or eighteen is a running gag throughout the series) has meanwhile become Black Jack’s secretary/major domo and gadfly. In ‘Sometimes Like Pearls’, she opens a unique parcel addressed to him which leads to some invaluable back-story as the solitary surgeon travels to see his great teacher and learns one final lesson…

‘Confluence’ provides a little twisted romance as the medical maverick loses out on a chance at love when undertaking a radical procedure to save a young woman from uterine cancer, whilst in ‘The Painting is Dead!’ an artist caught in a nuclear test endures a full brain transplant just to be able to finish his painting condemning atomic warmongers.

‘Star, Magnitude Six’ exposes the pompous venality and arrant cronyism, not to mention entrenched stupidity, of hospitals’ hierarchical hegemonies in a tale satisfyingly reminiscent of Steve Ditko’s H series and J series of polemical objectivist parables before the ruthless outlaw surgeon meets his female counterpart in the bittersweet ‘Black Queen.’

‘U-18 Knew’ moves us into pure science fiction territory when the unlicensed doctor is hired by an American medical facility to operate on a vast medical computer that has achieved true sentience, leading to some telling questions about who – and what – defines “humanity.â€

An annoying sidebar I feel compelled to add here: For many years broad, purely visual racial stereotypes were common “shorthand†in Japanese comics – and ours, and everybody else’s. They crop up here, but please remember that even at the time this story originated from, this was in no way a charged image; Tezuka’s depictions of native Japanese were just as broad and expressionistic. A simple reading of the text should dispel any notions of racism: but if you can’t get past these decades-old images, just put the book down. Don’t buy it. It’s your loss.

A heartrendingly powerful tale of determination sees a young polio victim almost fail a sponsored walk until an enigmatic stranger with a scarred face bullies, abuses and provokes him to finish. It also provides more clues to Black Jack’s past in ‘The Legs of an Ant’ before this first collection concludes with ‘Two Loves’ as a van driver deprives the greatest sushi artist in the world of his arm and his dreams when he runs him over. The lengths to which the driver goes to make amends are truly staggering… but sometimes Fate just seems to hate some people…

One thing should always be remembered when reading these stories: despite all the scientific detail, all the frighteningly accurate terminology and trappings. Black Jack isn’t medical fiction; it is an exploration of morality with medicine raised to the level of magic… or perhaps duelling.

This is a saga of personal combat, with the lone gunfighter battling hugely oppressive counter-forces (the Law, the System, himself) to win just one more victory: medicine as mythology, battles of a prescribing Ronin with a Gladstone bag.

Elements of rationalism, science-fiction, kitchen sink drama, spiritualism and even the supernatural appear in this saga of Japanese Magical Realism to rival the works of Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez. Mostly though, these are highly addictive tales of heroism; ones that that will stay with you forever.

© 2008 by Tezuka Productions. Translation © 2008 by Camelia Nieh and Vertical, Inc. All Rights Reserved.