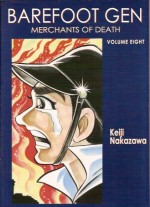

By Keiji Nakazawa (Last Gasp)

ISBN: 978-0-86719-599-6

The eighth volume of Barefoot Gen begins on 25th June 1950 with America again at war, this time with North Korea. Ardent anti-war protestor Gen Nakaoka is both disgusted and frightened as he explains to a classmate that even if Japan isn’t a participant it’s still in danger as the Occupation troops are using Japan as the major staging post for attacks against the Koreans. In Kyushu citizens are already compelled to operate nightly blackouts…

His lecture is abruptly interrupted by raucous laughter. Fellow student Aihara sneers at Gen’s sentiments. For him war is inevitable, profitable and beneficial to the race. A fight is only prevented by the arrival of the new teacher, Mr. Ohta, who lectures the whole class on the horrors of war, but once more Aihara derides the message.

Later Aihara and Gen meet to settle things in the time-honoured schoolboy manner, but the aggressive war-lover wants to use knives not fists…

Meanwhile Ryuta has become a super-salesman, selling dresses made by Natsue and Natsuko on Hiroshima’s street corners until the girls have enough money saved to open their own shop. He’s also become a devoted follower of the city’s woefully sub-par baseball team the Hiroshima Carp. On his return he finds a battered and bruised Gen talking of his fight with the clearly disturbed Aihara.

Naturally the valiant little fighter won, but now can’t get over the war-lovers reaction; begging that Gen finish it. He actually demanded that he be killed! The boys then swing by the baseball game where the see Aihara, crying bitter tears.

On the way home they encounter an anti-war march with teacher Mr. Ohta in the vanguard, despite the repressive anti-protest ordinances issued by the occupation forces (which were used with ruthless efficiency by the police and local government officers to suppress civil dissent, political opposition and especially the growth of a labour movement). When the police arrive they begin to harass the protestors until activists of the pro-war, pro-America Japan-Blood-and-Iron Party arrive and attack the pacifists. Things are getting ugly when Aihara appears, single-handedly breaking up the clash with devastating rhetoric and phenomenally well-thrown rocks. Inexplicably the war-lover’s only targets are the Blood-and-Iron thugs…

When Aihara is jumped and beaten Gen rescues him and gets him to a hospital. Finding his mother he learns the whole story. Aihara is just another bomb orphan who followed her home one day, but she replaced her own dead son with him and they endured. He learned to love baseball. Then they found he had leukemia. Ever since he has devoured any book or article about combat, but he is simply looking for a good way to die…

As he recovers it is Ryuta who finds a way to help him. Anyone who can throw like that – even a sick kid – should be pitching for his beloved Carp…

Later as Gen and Ryuta exit a movie theatre (life wasn’t unrelentingly grim, even then) they find Mr. Ohta, drunk as a skunk. The pressure is getting to him, and he drags the boys into a bar. It’s not just his job. He’s demoralised because he sees Japan sliding around its own Constitution, scant years after writing it, as the militarists that brought about the country’s downfall sneak back into power and trick the country into another fruitless war.

Shocked to hear the teacher’s own war-time experiences the boys get roaring drunk too. What else can they do?

On the fifth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, 3,000 police officers were deployed around the city to prevent peace rallies and protests. The people marched anyway and Gen and his friends were there. The next day they learn that Mr. Ohta will no longer be teaching them. Returning home they see another new evil – Methamphetamine Hydrochloride – a drug originally given to Japanese soldiers in the war “to stop them from getting scared” is now readily available in pharmacies. The nation’s young men are all becoming speed-freaks, injecting their lives away…

Forced out of his job, Mr. Ohta has also turned to the drug – until Gen talks him around. The next day Gen’s class all play hooky: they’ve decide to choose their own teacher, but the Principal and his stooges track them down, brutally beating them. Gen as always, resists, but Ohta demonstrates the power of passive resistance, gaining a moral victory and proving the worth of his pacifist convictions. Moreover the dissident will build his own school and prove there is a better way…

Rejected by the establishment for years, Ryuta cannot read or write: he becomes Ohta’s very first pupil.

As the war in Korea escalates tensions in Hiroshima grow, but amid the politics the kids have a more pressing problem. Natsue’s appendix was recently removed, but her wound won’t heal. The doctors keep operating but she’s fading…

The city is changing too. Capitalist profiteers and carpetbaggers are everywhere, flaunting their ill-gotten wealth whilst so many people still go hungry. A fight with a speculator in a restaurant ends with Gen nearly being beaten to death. Everywhere the monsters and criminals are regaining their pre-war positions of power, but at least Gen scores one small measure of utterly gratuitous vengeance…

And then authorities begin to clear the shanties built by the survivors whom they abandoned in the bomb’s aftermath. Everywhere ramshackle dwellings are destroyed; their inhabitants dispossessed for the second time in five years – except this time their leaders aren’t affected and actually profit from the tragedy. Gen and his brothers will soon be homeless again…

Life, even such a hard life as Gen’s, is all about change and struggle. As Koji finds a girlfriend and starts his own family and Natsue finds the courage to die on her own terms, the 13 year old Gen embraces again the words of his father and takes control of his path. His life will henceforward be lived on only his own terms.

Barefoot Gen: Merchants of Death is the most strident and polemical of the volumes to date: almost a graphic manifesto of how the world ought to be as much as a catalogue of its perennial mistakes. And yet even at its most bleak and traumatic Keiji Nakazawa’s magnum opus never forgets to be funny, compelling and enjoyably Human. This series should be on every school curriculum. At least you can keep it for homework…

© 2008 Keiji Nakazawa. All Rights Reserved.